Understanding Waterfowl: The Science of Disturbance

New technology is providing greater insights into how ducks respond to hunting pressure

New technology is providing greater insights into how ducks respond to hunting pressure

By Nicholas M. Masto, PhD; Abigail G. Blake-Bradshaw, PhD; Cory J. Highway; Bradley S. Cohen, PhD; and Jamie C. Feddersen

An adult hen mallard with a backpack-style GPS transmitter.

Researchers have studied how hunting disturbance affects waterfowl for nearly a century. Renowned waterfowl biologist Frank Bellrose recorded 50-fold increases in duck numbers in disturbance-free backwaters—areas he coined “natural sanctuaries”—in the 1940s. Bellrose concluded that “security constituted a principal factor governing the relative degree of use made of these areas by waterfowl.” In the 1970s, US Fish and Wildlife Service pilot-biologist Walter Crissey observed similar effects on duck distribution in and around national wildlife refuges and argued that the primary purpose of the refuge system was to concentrate birds in a general area to provide hunting opportunities for waterfowlers in surrounding communities.

In the past, scientific studies examining the impact of hunting pressure on waterfowl distribution were limited to observations of bird densities in sanctuaries versus hunted areas. However, new technology is providing a wealth of information about how individual birds perceive the hunting landscape, how and why they use sanctuaries, and how they react to different types and levels of disturbance. In fact, GPS transmitter studies from the Central Valley of California to the Mississippi Alluvial Valley have revealed just how sensitive ducks are to hunting pressure. These GPS tracking devices record the locations where ducks rest and feed—hour by hour—while researchers use other methods to simultaneously record hunting pressure and human disturbance on the same landscapes.

Ducks, like any prey species, weigh every decision against risks to their survival. The sound of an approaching mud motor or the sight of an ATV are all “risk cues” for ducks during the hunting season. Studies conducted by several research groups have shown that mallards respond predictably to these cues. By day, the birds crowd into places where people aren’t allowed. After shooting hours, they spill into nearby fields and wetlands to feed.

This safe-by-day, feed-by-night pattern isn’t new, but GPS telemetry has revealed just how consistently ducks adopt this behavior and how their movements and habitat use are influenced by the intensity of hunting pressure. In West Tennessee, we surveyed the presence of spinning-wing decoys from the air and determined that our study area was hunted almost continuously during the duck season, both on weekends and throughout the week. We also found that GPS-marked mallards clearly avoided heavily hunted areas during shooting hours and rarely prospected for new habitats, limiting their movements generally to two flights per day. Similar findings have been reported in Arkansas, Louisiana, and California. In short, disturbance reshapes daily and even weekly duck schedules. Following are more key findings from our research in Tennessee.

Over three seasons, we indexed hunting opportunity by using autonomous recording units to detect more than 339,000 distinct shotgun volleys in our study area. Two striking patterns emerged. First, hunting opportunities were greater (more shotgun volleys were detected) in areas that were close to sanctuaries compared to areas farther from sanctuaries, suggesting that undisturbed sanctuary areas benefited hunters. Second, when sanctuaries were intentionally disturbed as part of our study, daily shotgun volleys across the landscape dropped by roughly one-third. Thus, disturbing sanctuaries didn’t result in a wider distribution of birds. Instead, ducks hunkered down and actually moved less in response to disturbance on sanctuary areas.

Our research suggests that several small sanctuaries located in close proximity to each other will generate more “duck traffic” than a single large sanctuary will. Think of sanctuaries as a network of stepping-stones where ducks can hop from one safe area to the next. Our analysis showed that shorter distances between sanctuaries led to more duck movement.

When planning acquisitions or setting aside rest areas, managers should consider prioritizing proximity to other sanctuaries. Strategically placing rest areas across the landscape could help distribute ducks over a wider area and improve hunting opportunities. For agencies with finite budgets, acquisition of smaller rest areas surrounding large well-established sanctuaries (e.g., national wildlife refuges) might be a wise investment. Likewise, private land managers could partner with neighbors to create sanctuary networks between state and federal lands.

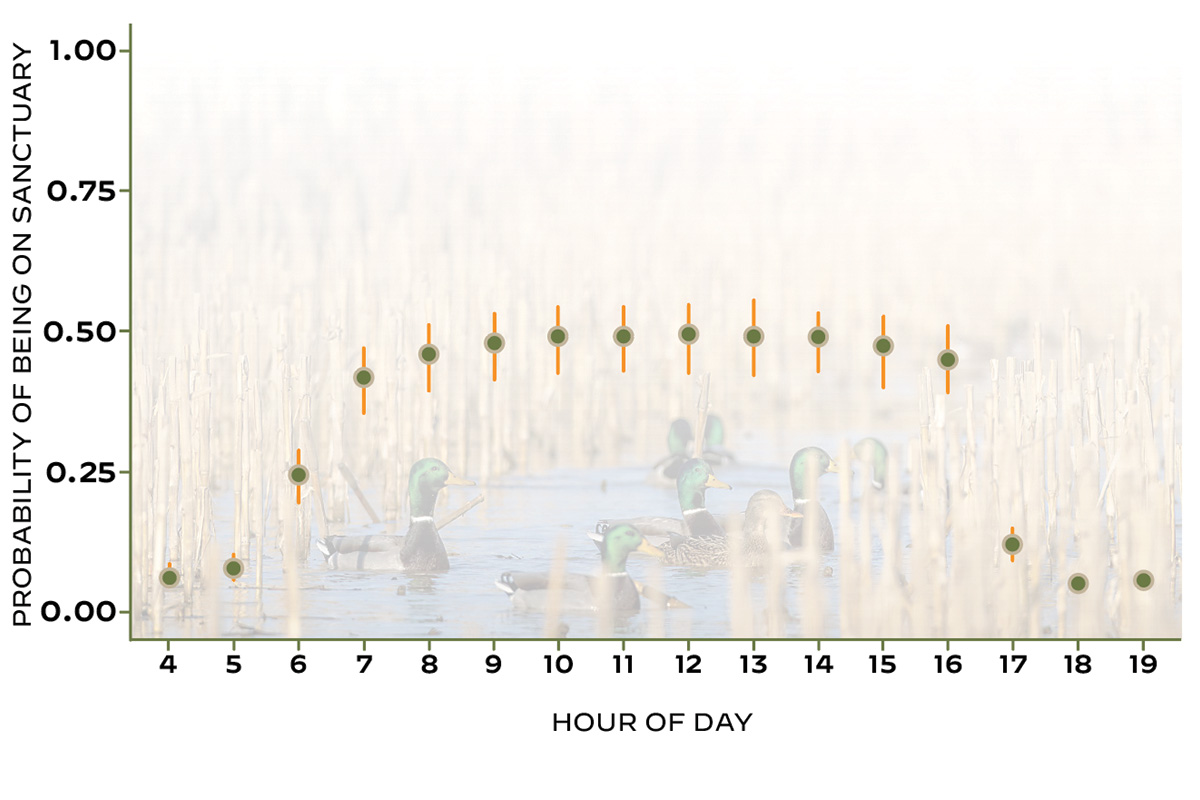

This graph shows the percent probability of mallards being on a sanctuary by hour of the day. Data were collected from GPS-tagged mallards in West Tennessee during winter 2019–22.

Proximity of sanctuary areas drives the probability that ducks will fly from one location to another (i.e., transition probability). The authors' research indicated that sanctuaries must be less than 10 miles apart for mallards to fly from one to another; otherwise, the potential for birds to alternate between refuges was essentially zero.

In many places, waterfowl managers try to reduce disturbance of waterfowl by closing areas at certain times of day or on certain days. Data from our research and other studies suggest that intermittent “temporal” sanctuaries are less effective than true no-access “spatial” sanctuaries. Limited-access days or noon closures certainly can help increase waterfowl use of crowded public and private hunting lands when no other alternative exists, but these measures are a poor substitute for true no-access spatial sanctuaries. Our data suggest that ducks perceive sanctuary in weeks, not days. Consequently, hunters may have to rest properties or hunting spots for a week or more to significantly improve their hunting prospects.

In many areas of the Mississippi and Central Flyways, land managers flood large areas of high-energy crops. Ducks know it. Our research found that landscapes that offer a combination of daytime sanctuary and high-quality food resources will attract more birds and hold them longer than areas with only one of these habitat components. If hunters are unable to provide food and sanctuary on the same property, they should work with neighboring landowners to provide both habitat components in as close proximity to each other as possible. The distance between safety and forage is the “management lever” for waterfowl.

Yes, ducks loaf on sanctuaries during shooting hours. Yet research also indicates that providing sanctuary can keep birds in an area longer, providing additional opportunities for hunters on surrounding lands. GPS studies have also shown that ducks do in fact leave sanctuary areas on a daily basis, and when sanctuaries are close to huntable ground, those often short but predictable flights can put more ducks over your decoys.

Ducks aren’t disappearing—they’re adapting to a landscape in which suitable wetland habitat is shrinking, and hunters have better access to these areas than ever before. Fortunately, biologists have some amazing technology to keep track of duck behavior as the birds adapt to our activities. In human-dominated, heavily hunted landscapes, mallards make the same calculations every day: safety first, food second, and keep the commute as short as possible. When we provide true daytime sanctuary and place those safe areas within easy reach of quality foraging habitat, ducks will keep using the landscapes that we hunt. Ducks move more and stay longer, and we see more hunting opportunities if both of these components are available. In short, sanctuary—alongside natural and managed habitats for food—is a critical component of the wetland habitat complex that migrating and wintering ducks need to thrive. Done right, sanctuaries don’t wall ducks off from hunters but instead provide hunting opportunities throughout the season.

Dr. Nicholas (Nick) Masto is a waterfowl ecologist with the US Fish and Wildlife Service Habitat and Population Evaluation Team. Dr. Abby Blake-Bradshaw is a postdoctoral researcher at the Forbes Biological Research Station. Cory Highway is a doctoral student and Dr. Bradley Cohen is associate professor at Tennessee Tech. Jamie Feddersen is migratory gamebird coordinator with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy