Bellrose

A look back at one of the giants of waterfowl conservation

A look back at one of the giants of waterfowl conservation

By Chris Madson

Frank Bellrose (right) and James S. Jordan band a mallard in 1948 as part of their ongoing studies of waterfowl along the Illinois River.

After all these years, the memory is little more than a few images. I was a graduate student in the Department of Wildlife Ecology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. My new wife, Kathleen, and I were coasting to a stop under the shade of the silver maples a stone’s throw from a backwater of the Illinois River in front of a modest frame building that served as the headquarters of the Illinois Natural History Survey’s world-renowned waterfowl research effort.

I don’t remember why we were there—as a graduate student, I’d probably been sent to pick up samples for the ongoing investigation of lead poisoning in waterfowl, which had been a focus of the station for more than 20 years. As we climbed out of our dilapidated Chevy station wagon, I was amazed to see Frank Bellrose, the director of the station and one of the era’s best-known waterfowl specialists, coming out of the front door to greet us. He shook our hands and invited us into his humble office. A lowly graduate student like me had no right to expect this kind of red-carpet treatment. We chatted for 20 minutes, transacted whatever business I’d been sent to conclude, and then Kathy and I stood to leave. As an afterthought, he asked, “Say, would you like a copy of the book?”

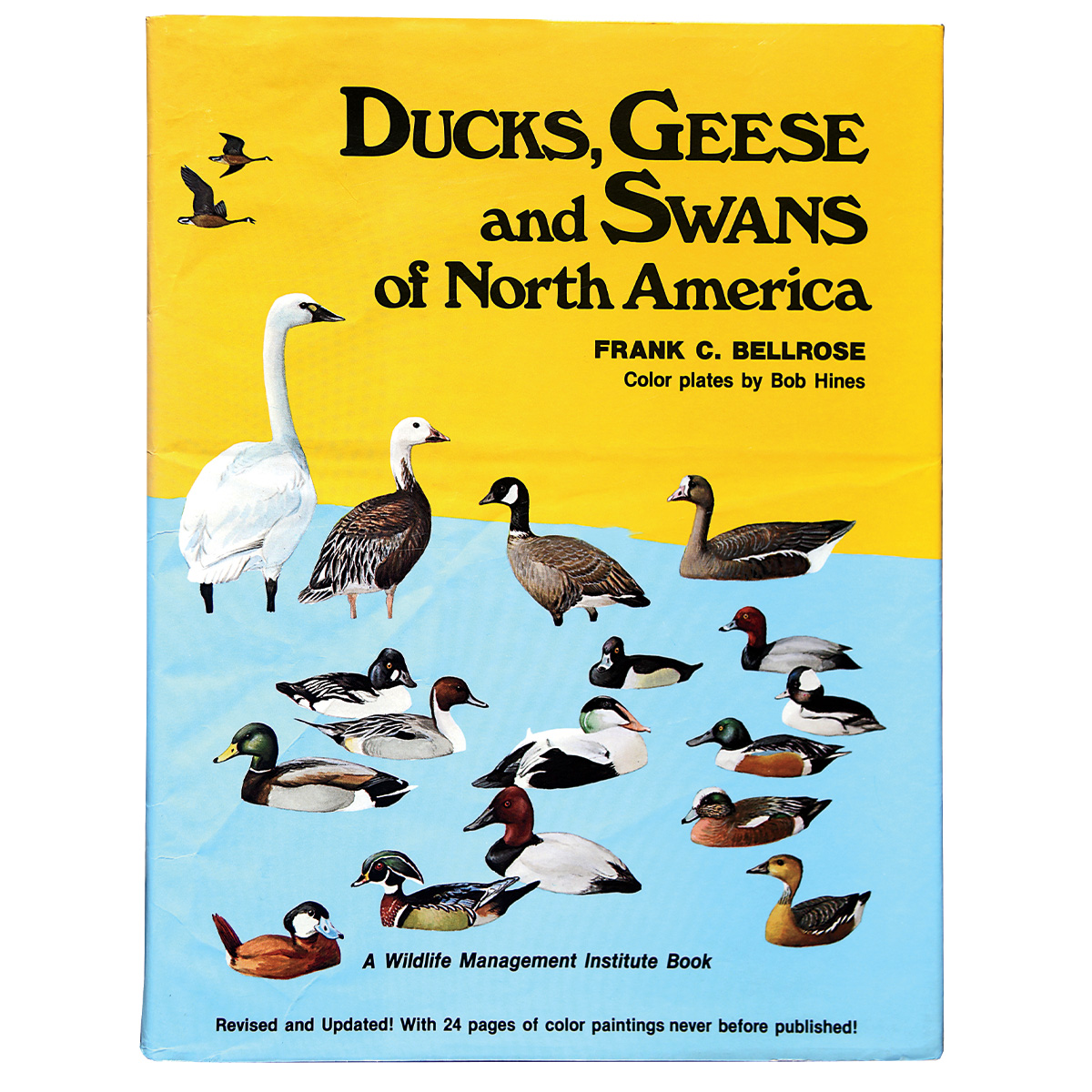

“The book” in question was his Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America, a reference that had just been published but had quickly become an indispensable resource for anyone in the field of waterfowl management. I’d already taken a serious bite out of my monthly wage as a research assistant to buy a copy, and, anxious to demonstrate my admiration for the work and its author, I said so. Kathy looked at me strangely, turned to Frank, and said, “Well, I don’t have one.”

The Frank C. Bellrose Waterfowl Research Center is housed within the Forbes Biological Station—North America’s oldest inland field station—which was established in 1894 near Havana, Illinois.

He hurried out and came back a minute later with a fresh copy. It’s open to the flyleaf as I write this, signed by the author: “With best wishes to Chris and Kathy Madson—Frank C. Bellrose.” Kathy often reminds me that this is her book.

The memory of Frank’s warmth and genuine interest in two young people abides with me to this day. Over the decades that followed, I found out that this was his way with everybody he met—among them four generations of waterfowl professionals who valued his friendship as much as they admired his work.

He came into the world in the summer of 1916 in the little town of Ottawa, Illinois, a settlement perched on a bluff overlooking the Illinois River. That accident of birth may explain a lot about the way he turned out.

Since the retreat of the last glacier, the Illinois River has exerted a powerful influence on the people along its banks. The immense natural wealth of the valley had supported a thriving human population for 9,000 years before the summer of 1674, when the Jesuit priest Jacques Marquette and his partner, Louis Jolliet, with five voyageurs in two canoes, came up the river on their way home to Montreal.

They had heard of a different route to Lake Michigan—a river that would spare them the rapids on the upper Mississippi and lower Fox. It was the Illinois, a tranquil stream with a languid current and no rapids that would impede a canoe, a waterway that led almost straight northeast to a portage of six miles across a low divide to a stream that flowed into Lake Michigan. They took the detour.

Bellrose’s interest in birds began with his quest to earn a Boy Scout merit badge and grew into a career that helped define modern waterfowl science.

For more than a year, they’d traveled through some of the richest game country in North America—an endless display of wild abundance on which they often commented—but what they saw in the valley of the Illinois left them in awe. “We have seen nothing like this river that we enter,” Marquette wrote in his journal, “as regards its fertility of soil, its prairies and woods; its cattle, elk, deer, wildcats, bustards, swans, ducks, parroquets, and even beaver.”

Just 13 years after Marquette’s journey, a French fur-trading post was established within a few miles of what, more than two centuries later, would be Frank Bellrose’s hometown. Through the last half of the 19th century and into the 20th, the valley was one of America’s legendary waterfowling areas. As early as 1880, wealthy hunters began establishing private duck clubs along the river, attracting patrons from as far away as Cincinnati and St. Louis. In the 1880s, the master carver Robert Elliston and his wife, Catherine, began producing decoys for sale to local hunters from the village of Bureau on the Big Bend of the river, the start of what came to be known as the Illinois style. In 1904, farmer and avid waterfowler Philip Olt revolutionized duck call design with his hard rubber D-2 model, manufactured and sold in Pekin, Illinois, on the banks of the river.

The young Bellrose was undoubtedly influenced by the waterfowling tradition along the Illinois, but it was the broader ecological spectacle in the valley that captured his imagination. As a 13-year-old Boy Scout, he was in hot pursuit of merit badges, but one seemed out of reach. It required a young scout to identify 40 species of birds.

“I thought the requirement insurmountable,” he remembered more than 60 years later, “and told my father that I didn’t think there were 40 different birds in the vicinity. My father armed me with a bird book and field glasses and urged me to find out. It wasn’t long before the locating and identifying of birds became a serious interest. It persisted long after the merit badge was secured.”

A pioneer in the growing science of wildlife survey techniques, Bellrose began a weekly count of waterfowl along the Illinois River in 1938. He expanded and refined the survey over the years, and it continues today.

The next year, he took to the water.

“When I was 14, my parents bought me a canoe, and I found that paddling that area’s waterways was not only a great release for adolescent energies but also allowed me to visit a theretofore hidden world of mystery on and along the area’s streams. The sights and sounds and smells of those water courses were perfect fuel for a boy’s questioning nature and yen for ‘wilderness’ adventure. The world visited by canoe is a very special place.

“Early in the Thirties, the Illinois River was dammed below Ottawa. The impoundment and its backwaters always seemed to hold ducks. My ornithological fascination shifted then from songbirds to waterfowl.”

Bellrose pursued that fascination through his college career, graduating in 1938 from the University of Illinois with the stated career goal of “duck study.” His timing was fortunate because it had become abundantly obvious to conservationists and the public at large that ducks needed help.

With the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918 and the rise of effective enforcement of federal hunting regulations, North American waterfowl had staged a modest comeback from low numbers at the turn of the century, but the increasing power of machinery and the expansion of federal budgets had led to massive drainage and flood-control projects along the nation’s major rivers. The loss of these sloughs and backwaters dealt a severe blow to birds migrating from the breeding grounds, and the catastrophic drought of the 1930s compounded the impact.

Alarmed by the trend, the federal government established the cooperative wildlife research units at major universities, instituted the Pittman-Robertson excise tax for conservation, and dramatically expanded the national wildlife refuge system. Private citizens banded together to establish the National Wildlife Federation and, in 1937, Ducks Unlimited. The call to action was not lost on the Illinois Natural History Survey, a unique state-funded institution that had been studying wildlife and wild places in the region since 1858. In 1938, the survey was anxious to tackle the waterfowl problem in greater depth and was pleased to discover a freshly minted graduate from a local university with a passion for “duck study.”

In 1976, Bellrose authored a comprehensive update to Ducks, Geese and Swans of North America, which was originally published in 1942. For decades, it has been an essential reference for biologists, birders, waterfowlers, and anyone else who has a passion for these birds and their habitats.

Bellrose jumped right in. That first duck season, he started a weekly survey of waterfowl on the marshes along the Illinois River. It was one of the earliest efforts to put a number on waterfowl populations across a wide area. After World War II, the Illinois Natural History Survey joined the nascent effort to count ducks and geese from small aircraft, a change in equipment that allowed surveys across a much wider area and with generally greater accuracy. The waterfowl census Bellrose began continues to this day.

As he set out to estimate how many ducks and geese there were in the area, he also started trying to figure out why there weren’t more. He didn’t have to look far.

“Since 1900,” he wrote in 1944, “almost 200,000 acres of the Illinois River bottomland subject to overflow have been leveed and drained. A similar condition exists along the Mississippi where drainage districts extend almost continuously from Rock Island to Cairo.”

Many of the owners of the duck clubs along the Illinois River wanted to know how they could attract waterfowl to the wetlands that were left, so Bellrose began studying native marsh plants on the river, looking for species that produced the most duck food and finding ways to encourage growth of those plants. He continued the project off and on for the next 40 years, developing techniques along the way that marsh managers still use to produce natural duck food in what is known today as moist-soil management.

While he worked on the challenge of improving habitat for all the waterfowl that visited the Illinois Valley, he took time to focus on the one duck that spent its entire year in the vicinity. “The wood duck is special to me,” he wrote after more than 50 years of research on the species. “It is special because it was where I was able to investigate it closely, which was a definite advantage. And its habitat preference, physiology, and behaviors have convinced me over the span of half a century that it truly is the most unique of North American waterfowl.”

For decades, Bellrose studied the effects of development on waterfowl and their habitats. He also helped expand and improve wildlife survey methods by counting birds from small aircraft.

When Bellrose started his wood duck research, hunting seasons on woodies had been closed for 20 years following decades of unregulated harvest before the Migratory Bird Treaty Act became law. The loss of vast tracts of old-growth bottomland timber, which contained the natural tree cavities used by nesting wood ducks, also slowed the recovery of the population.

In the late 1930s, a handful of wildlife managers had begun experimenting with nest boxes for wood ducks. Bellrose and his colleague Art Hawkins launched a long-term experiment to improve the first designs to better attract wood duck hens and, at the same time, offer some refuge from the host of predators that raid wood duck nests in the wild. The results of their work proved to be highly popular with wood ducks—and the public. By the 1980s, Bellrose estimated that more than 100,000 nest boxes had been installed by wildlife agencies and private citizens, adding 4 or 5 percent to the fall population of woodies east of the Mississippi. Bellrose would go on to literally write the book on the species: the authoritative monograph, Ecology and Management of the Wood Duck, published in 1994.

Given his passion for waterfowl, it was inevitable that he would eventually delve into the broader environmental trends that affected waterfowl and most other wildlife through the 20th century. As he analyzed the ecology of marshes along the Illinois River, he observed changes in water quality that caused a decline in many of the aquatic plants that waterfowl relied on for food.

“Increased turbidity and sedimentation were responsible,” he wrote in 1981. “Three factors—soil erosion, the high velocity of tributaries, and the sluggish flow of the main channel—together have brought about an environmental disaster: backwater lakes of the Illinois River are filling at a rapid rate leading to their early extinction.”

There were few areas of waterfowl biology and management that Bellrose didn’t influence. He conducted extensive research on wood ducks and their habitats, investigated issues related to lead poisoning in waterfowl, and developed new methods and technologies to study bird migrations.

And then there was the growing problem of lead. As early as 1893, pioneer conservationist George Bird Grinnell had become aware of lead poisoning in waterfowl near Galveston, Texas. He examined several dead birds from the area and discovered that the ingestion of spent lead pellets was responsible. Over the next 50 years, other observers confirmed Grinnell’s observations, but no one had tried to measure the extent of the problem until the winter of 1948, when thousands of mallards died of lead poisoning on the lower Illinois River. Supported by a major grant from Winchester Arms, Bellrose began the first comprehensive study of the problem. He collected information on die-offs across the country, sampled the bottoms of heavily hunted marshes, dosed wild mallards with lead pellets to study their effect on the birds, tested the effect that different kinds of food had on the toxicity of lead in a mallard’s bloodstream, and X-rayed thousands of ducks he trapped in the wild, looking for lead pellets in their gizzards.

In 1959, after a decade of his own investigations and a growing body of information from other researchers, he offered the first analysis of the effects of lead poisoning on North American waterfowl. Among many other findings, he estimated that “each year, approximately 4 per cent of mallards in the Mississippi Flyway die in the wild as a result of lead poisoning and that an additional 1 per cent of the mallards in the flyway are afflicted with lead poisoning but are bagged by hunters. For all waterfowl species in North America, the annual loss due to lead poisoning is estimated to be between 2 and 3 per cent of the population.”

Over the next 30 years, as the controversy surrounding lead poisoning reached a crescendo, Bellrose and his colleagues at the Illinois Natural History Survey contributed a steady stream of research to the debate. The first limited nontoxic shot regulations were put into effect on a few national wildlife refuges in 1972, but the nationwide requirement wasn’t adopted until 1991.

As complex and politically fraught as the lead poisoning issue was, it didn’t occupy all of Bellrose’s time. For much of his career, he was fascinated by the phenomenon of bird migration. He and his colleagues at the survey used radar to understand how wind direction, cold fronts, and cloud cover influence the timing of migration flights among songbirds. He trapped mallards on the local waterfowl refuge and drove them miles into the night before releasing them to find out whether the ducks were using the stars to navigate after dark—they were. He proved that juvenile blue-winged teal could find their way south without any help from their parents or other teal. He found that the longer a young duck lives in a given place, the more likely it is to return to that place after it’s been released somewhere else. And with the help of a cadre of waterfowl biologists and managers across the country, he broke the major flyways down into much tighter migration corridors, species by species, with more accurate estimates of the birds’ arrival times and departures.

Frank Bellrose kept working on behalf of waterfowl until his passing at the age of 88. He is remembered as one of the world’s most influential voices in wildlife management and conservation.

Bellrose never stopped working on and for waterfowl. He stayed with the Illinois Natural History Survey until 1991, “retiring” after 53 years with the outfit at the age of 75 to devote more attention to his masterful book on the wood duck. For a time, he also wrote a popular waterfowl ecology column for Ducks Unlimited magazine. He was working on a complete revision of Ducks, Geese, and Swans when he died in 2005 at the age of 88.

It should probably come as no surprise that waterfowl have drawn the attention of so many of America’s brightest naturalists over the centuries—these birds have always been among the continent’s greatest wild spectacles, justifiably famous for their sheer numbers, their flamboyant colors and customs, and their magnificent annual passage from the tundra to the tropics and back. From George Bird Grinnell and Teddy Roosevelt to Ding Darling and Aldo Leopold, the list of people who have classified them, studied them, followed them to the far reaches of the continent—fought for them—is a pantheon of conservation giants.

Over a long career, Frank Bellrose earned a place in their ranks. There was hardly any element of waterfowl biology, behavior, conservation, health, biopolitics, or management that he didn’t leave better than he found it.

In the foreword to Bellrose’s wood duck book, his lifelong colleague and friend Art Hawkins offered what may be the best tribute to the man and his work: “If ducks could hold a contest to decide which human was their greatest benefactor during the past half century,” he wrote, “Frank Bellrose most likely would win.”

Most likely.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy