Sunrise on the Santee

An Iraq War veteran shares a blind with fellow warriors during a special hunt in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, where he experiences the healing power of the outdoors and discovers what it means to be living in the black

An Iraq War veteran shares a blind with fellow warriors during a special hunt in South Carolina’s Lowcountry, where he experiences the healing power of the outdoors and discovers what it means to be living in the black

By Oliver Hartner

A star-studded sky hung over Annandale Plantation near Georgetown, South Carolina, heralding the promise of a cloudless morning. As we prepared for a day of hunting the area’s abundant wetlands, balmy temperatures incubated a hatch of mosquitos that swarmed from the swampy mire, and our headlamps drew them to us like a dinner bell. Before heading to the blind, I shed a couple layers and excavated a bottle of bug spray from my car.

Through the darkness, we paddled Beavertail boats to an island of spartina grass sprouting from the waist-deep brackish pond. Our oars dug at the water, and the earthy odor of pluff mud floated on the tepid air. Our guide, Avery Williams, led Pete Klimek and me past an alligator, whose rubied eyes glowed just above the surface. I couldn’t help but think about that gator when we hid the boats and waded to our blind.

Flocks of teal rose from the pond as we made our way toward the grassy redoubt. Those ducks were flying low enough that we could have caught them with our bare hands. With decoys deployed, we sat in silence and watched as scores of waterfowl returned—oblivious to our presence—to loaf and feed on wigeon grass, distorting the glassy surface of the water. The sun began its ascent, and an impressively large Sabal palmetto tree revealed itself in the nascent light, guarding the marsh with its massive size and sharp fronds.

Guide Avery Williams readies a blind during a 2025 warrior hunt in South Carolina.

Guides and hunters gather before the morning’s hunt.

I felt an overwhelming sense of awe and appreciation for the role that fortune, circumstance, and magnanimous people played in my being able to witness this natural splendor, and my mind drifted from the present to the past through a rent in space and time. I saw myself 22 years younger, carrying a crew-served weapon over my shoulder and happy to have survived another sortie through the urban decay of Baghdad. The noxious yet intoxicating odor of JP-8 fuel from idling Abrams tanks floated on the air, intensified by the arid heat of summer in the sandbox.

Through the torrid air dancing on the horizon, I saw Sergeant David Murray—a member of my platoon—materialize like a mirage. He approached with a deliberate gait and a friendly wave before getting close enough to take custody of the .50-caliber machine gun that was balanced over my shoulder. He informed me that he and his team were taking our vehicle because theirs was being serviced, and I remembered the joy of not having to labor under the weight of that weapon for another step. Had I known this was to be our last conversation, I would have said so much more. Their patrol would be struck by an IED, Sergeant Murray would be killed, and others in his team would be severely wounded.

While I was spared life and limb during my time in Iraq, my wound was a guilty heart. Murray and I attended high school together. I recruited him into our unit. And though he is interred in good company at Arlington National Cemetery, I feel obliged to atone for what the world lost with his early departure from this life.

Pete Klimek paddles through the marsh.

Time can heal a troubled soul, but scars often remain, serving as a reminder of life’s trials and travails. Many wounds, whether physical or psychological, never mend if left untreated. Finding a connection with the natural world can often provide a necessary salve for the invisible wounds borne by many veterans. Fortunately, there are organizations like the Andy Quattlebaum and Blackwell Family Foundation (AQBFF). With a passion for both conservation and veterans’ causes, AQBFF helps veterans find peace and perseverance through waterfowling.

Andy Quattlebaum lost his life at the tender age of 22, but his passion for conservation and veterans’ causes lives on through the work of the foundation that bears his name. Andy’s father, Don Quattlebaum, and its current executive director, Ed Dennis, first met 12 years ago through Dan Ray, a trustee of DU’s Wetlands America Trust, who asked Don to help him expand his veterans’ support hunts. Don honored his request and hosted a pair of veterans at White House Farms, one of which happened to be Ed, marking the beginning of an enduring and fruitful friendship with the Quattlebaum family.

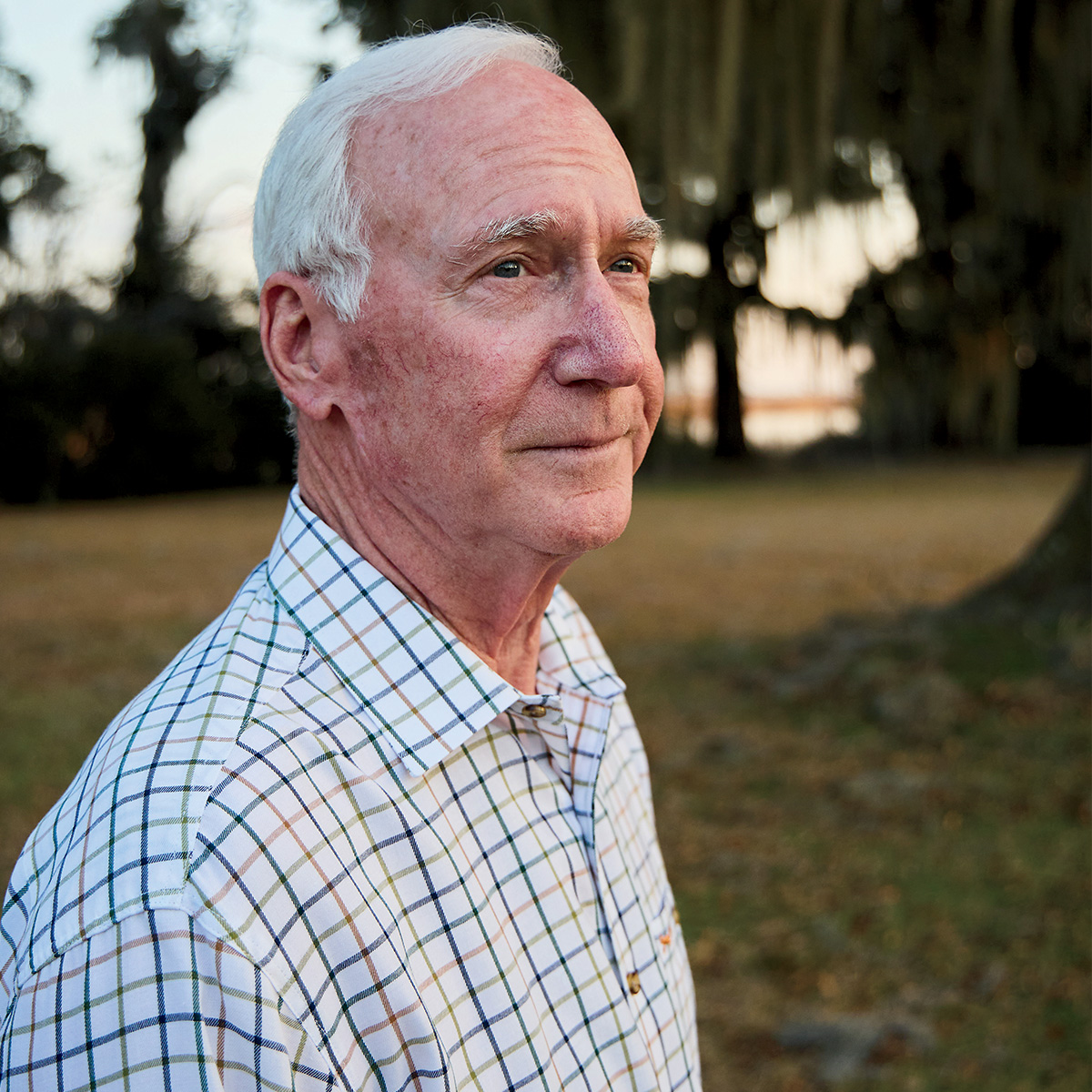

Don Quattlebaum

“We had Ed and Trevor Peterson down to hunt with us year after year after that first one, and we would go to Ed’s place and hunt pheasants. Andy loved being around Ed, Trevor, and other veterans while hosting these hunts,” Don said.

Ed recalled meeting Andy for the first time and noticing the vintage watch he wore, saying, “From the time I met him, Andy was always wearing his grandfather’s watch from World War II out of respect and remembrance of his service. Andy felt compelled to honor all veterans, even those outside his immediate family, and aside from conservation, veterans’ causes were truly one of his passions.”

After Andy’s untimely death, Don called Dan and asked if he could bring the veterans’ support hunts under the purview of his foundation in honor of his son. Not only did Dan support this transition, but he offered up his property, Annandale, as a venue to host the veterans. “As a veteran myself, I’ve always appreciated what it is these men and women do in service to our country. And though I’ve been involved with these hunts since 2012, I still love being a part of them and seeing veterans, especially first timers, come out and enjoy waterfowling and the resource,” Dan said.

The 2025 warrior hunt was organized by the Andy Quattlebaum and Blackwell Family Foundation and by Quilts of Valor. Veterans taking part in the annual event enjoy waterfowling in some of the Lowcountry’s most storied locations.

AQBFF remains committed to hosting veterans from across the United States at some of the most storied waterfowling locations in South Carolina’s Santee Delta, as well as continuing its work to support conservation. During this past year its efforts included partnering with the James M. Cox Foundation to fund a major donor project through Clemson University and Ducks Unlimited. The deliverable of this funding will be an online research-based tool to help landowners in the Santee Delta make decisions about how to improve habitat while preserving the historical and cultural significance of this region.

Soon after taking over the veterans’ hunts from Dan, Don faced the challenge of having to hire a new executive director for the foundation after its former head was diagnosed with cancer. Don wanted the AQBFF to have a leader who knew Andy and had a deep appreciation for the causes Andy valued. While visiting Don during duck season, Ed mentioned that he wanted to move from his native state of New York and thought Tennessee might be a good place to call home. Don replied, “Well, if you’re just leaving New York for a new place, why don’t you move here and be our executive director?”

(From left) Pete Klimek and the author take aim at incoming birds while Avery Williams looks on.

Ed took him up on the offer, and he relocated to Georgetown, South Carolina, in time to plan and execute the second annual AQBFF Warrior Hunt, which has grown from hosting 16 veterans to 48. “I feel honored and privileged to have been given this opportunity by Don, and every day I go to work is another opportunity to honor Andy’s memory while helping do some good in the world,” Ed said.

For me and the other veterans participating in the 2025 warrior hunt, the weekend started at Camp Woodie, a 1,600-acre wildlife education center near Pinewood, South Carolina. During our 36-hour stay, we were well fed and feted by the AQBFF and Quilts of Valor—a nonprofit organization that creates and presents handmade quilts to veterans. It was in this liminal space that I realized how long it had been since I’d been around so many veterans. It felt empowering and humbling to be among people with the shared experience of military service and to be numbered among them. Our experiences ranged from those who served in the Vietnam War to those who separated from service after major operations in Afghanistan and Iraq. There was representation from both the enlisted and officer corps, ranging from Major General to Lance Corporal—all of us were equals in our love for the resource and conservation.

We woke the next morning and had a hearty breakfast before splitting into groups for a round of sporting clays and a tower shoot. These two events offered an exceptional introduction to wingshooting for those who had never handled a shotgun or shot at a live target. It also gave us a chance to meet the team members we would be hunting with the following morning. Our team leader, Joe Fancher, has enjoyed waterfowling since childhood, and his time with the Army Special Forces afforded him duck hunting opportunities across North and South America. He also hunted with Dan Ray when the veterans’ hunts were in their infancy.

The author and fellow veteran Pete Klimek bagged full limits of wigeon and teal during their Lowcountry experience.

“When Don and Ed took these hunts over, they were interested in growing them into something bigger, and a good number of us have worked with other foundations and had an idea of how to do it,” Joe said. For this year’s hunt, Joe recruited A.J. Johnson, a former special operations Marine, and Rob Thompson, US Army Special Forces, both of whom felt compelled to become more involved with the effort. “This is such an amazing opportunity, and I want more veterans to have the experience of coming down here and spending time with some truly wonderful people outdoors,” A.J. said.

One of my friends and a fellow veteran who is still serving, Lieutenant Colonel James Smith of the South Carolina Army National Guard, also joined our team for the hunt. After resigning his commission as a Judge Advocate General officer to enlist in the infantry, James fought in Afghanistan before returning to the officer corps to lead a battalion. Pete Klimek, who shared a blind with me, represented the youngest veteran of our cohort, and until this hunt he had never done any kind of wingshooting. “I’ve wanted to try duck hunting for so long but never had the opportunity until now, and I couldn’t be more grateful for this experience,” Pete said.

Our team caravaned from Camp Woodie to White House Farms for a banquet and fundraiser benefiting the South Carolina Waterfowl Association and—through a dollar-for-dollar matching gift from AQBFF—FourBlock and Upstate Warrior Solution. FourBlock, a nationally recognized nonprofit, focuses on helping veterans transition into the civilian workforce. Upstate Warrior Solution, a nonprofit based in Greenville, South Carolina, serves as a one-stop shop for veterans needing help with anything from navigating the US Department of Veterans Affairs to alcohol addiction.

Many people and organizations are involved in putting the hunt together. All are united by a desire to say thank-you to our veterans and to provide a setting for camaraderie and healing.

After the banquet, Joe led us down the highways and byways of the Santee Delta toward Annandale. As we drew nearer, the lights of our cars offered teasing foretastes of its majestic beauty. Annandale’s ancient oaks embraced us with long limbs draped in Spanish moss while a harmonious chorus of crickets and katydids sang us to sleep. In the morning I met my guide, Avery, and partnered with Pete, hoping that I’d see him harvest his first duck.

From the back of our blind, Avery confirmed that shooting time had arrived, and a team of teal buzzed us before we could shoulder our shotguns. Those birds picked up another flight before descending into the decoys. At Avery’s signal, we rose to shoot. The flock broke in all directions like a rack of billiard balls, escaping and evading our erratic opening salvo.

Other blinds that were within earshot erupted with shotgun fire as we reloaded and waited for another opportunity. Groups of teal raced around our blind, presenting passing shots as their wings whistled against the air, but we held our fire and waited for wigeon and bigger ducks to appear. Avery worked them in with a 6-in-1 whistle and intermittent mallard calls. Then, breaking the cadence of his siren song, he said, “OK, let’s get on the board here, fellas.” As the teal flashed over the decoys, Pete connected on a crossing shot, sending a drake greenwing to the water with a splash.

Wetlands America Trust Trustee Dan Ray hosts hunters at Annandale Plantation.

We celebrated Pete’s first duck, but before we could retrieve it, more teal sped in from behind us. I emptied both barrels of my side-by-side at a pair of greenwings without taking either one, disappointed that they didn’t fall but happy that I’d missed them clean. I breached the gun and replaced the spent shells just as a wigeon pair presented themselves. They came in on cupped wings, and as we stood to take our shots, Pete connected with the hen. His borrowed Browning A-5 barked twice more as the drake ascended, leaving the gun empty. Before the drake could climb out of range, I dropped my finger to the back trigger of my double gun and felled him with the full-choke barrel. While I wished Pete had gotten the double, bagging the drake with a back-trigger shot decluttered my mind. As more ducks flew into effective range, I realized there was no cause for trigger-happy urgency, given the remarkable number of shooting opportunities.

The ducks were as committed to this habitat as the landowners who cultivated it, and before anyone else returned from their blinds, Pete and I each hauled out limits of teal and wigeon. Because of Dan and Don’s generosity, Pete had joined the ranks of waterfowlers, and that fact alone made the hunt a success.

Lieutenant Colonel James Smith of the South Carolina Army National Guard.

Avery took us back to the barn, where we watched as other members of our team returned with their limits and gathered for a group photo. We then departed Annandale for a Lowcountry barbeque that was waiting for us at White House Farms, offering us another chance to congregate and exchange stories about our hunts before saying farewell. I briefly stole away and took a walk along the dikes and rice trunks of White House Farms, grabbing one last look at the waterlogged landscape painted across the horizon. Long, alternating brushstrokes of green and blue blended together as ripples in the rivulets shimmered with sunlight. For generations, the enslaved populations of this region’s plantations toiled—in many cases to death. While this painful scar cannot be denied or removed, neither can the healing that these places now provide through their current custodians.

I thought of something another veteran said to me after I told him about my experiences in Iraq and the loss of Sergeant Murray; how I wondered if I was living a life worthy of my friend’s sacrifice, and how humbling it felt to be around these other veterans who’d given more of themselves during their service than I had. He listened and replied, “You’re in the black, Hartner. You don’t owe anything.”

His simple response comforted me in a way that others over the years had failed to do. Had it not been for the difficult work and tremendous generosity that went into pulling this hunt together, I might never have received this grace. Andy’s quote, “Believing is better than hoping,” serves as a call to action for the foundation that bears his name, and through its efforts on behalf of veterans and habitat restoration, healing happens.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy