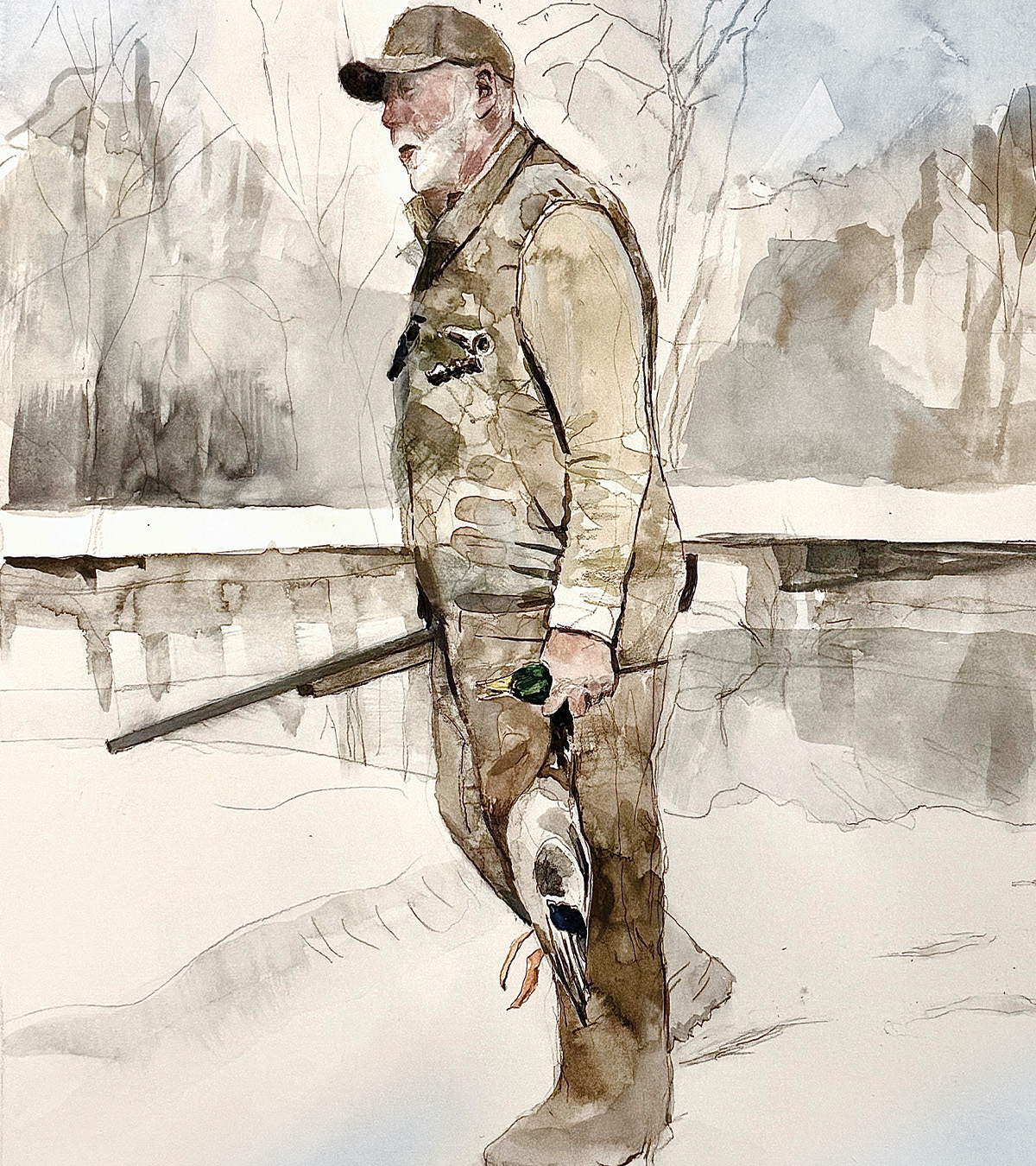

Just One Mallard

On a frigid Montana day, an aging hunter says good-bye to an old friend

On a frigid Montana day, an aging hunter says good-bye to an old friend

By Dave Books; Illustrations by Frederick Stivers

When I went down to the sport shop this year to get my migratory bird license, I was asked the usual questions required for the federal HIP survey. HIP stands for Harvest Information Program, and it’s designed to gather data on the number of ducks, geese, and other migratory birds taken by hunters each year. When the young fellow behind the counter asked me how many ducks I’d shot the previous fall, my answer was a little embarrassing: “Just one mallard.”

He arched his eyebrows, but at least he didn’t laugh out loud. I felt like I owed him an explanation, but the store was busy and I knew he didn’t have time to listen. I wanted to explain that I just hadn’t had the heart to hunt the previous fall because Bailey, my Labrador retriever, had crossed the rainbow bridge a few months before the waterfowl opener. She had been my boon companion for 15 years, and hunting without her didn’t have much appeal.

I wanted to tell him how I pulled my camper from Montana to eastern South Dakota to pick her up when she was eight weeks old, and how she snuggled into my sleeping bag those first few cold June nights to fend off the chill. I wanted to tell him how I “baptized” her with Yellowstone River water on the way home, not long after crossing the state line into Montana. I wanted to tell him about the countless adventures we had together hunting ducks, doves, pheasants, and grouse all those years. Most of all, I wanted to tell him how and why I had shot that one mallard last season, and that I really hadn’t gone to the river to hunt that day but to spread Bailey’s ashes in a place we both loved.

The time to say the final good-bye came on a blustery November afternoon, and I drove to the river with a heavy heart. It was the kind of day that gets migrating waterfowl on the move and stirs the souls of duck hunters everywhere. I thought about leaving my shotgun in the truck, but at the last minute I took it along with the idea that I might fire a salute to mark the moment. To make walking a bit easier, I opted for hip boots instead of chest waders and left my heavy parka and decoys in the truck.

There were several inches of fresh snow on the ground, and the river was eerily quiet as I hiked the quarter-mile to the spot in the channel where I had set out my decoys so many times. As wet snowflakes filtered down, I let Bailey’s ashes drift with the wind and said a silent prayer as the dark water took them in. Then I paused for a time, thinking about how mallards always got my heart pounding when they set their wings and planed down to the decoys, the drakes’ emerald heads and bright orange legs flashing in the sun.

I hadn’t seen any ducks in the air above the channel or over the main river when I walked in. Then, as if on cue, a flock of mallards appeared downriver, flying low, necks craned, looking for a place to land. When they rounded the bend in the channel and bore straight toward me, instinct took over. I shot once and killed the nearest drake, hoping he’d fall near enough to shore for an easy retrieve. I knew the water in the channel was only about thigh deep, and I also knew it might be tricky wading with hip boots.

The drake wasn’t as close to shore as I had hoped, and though the current in the channel was slow, he was moving steadily downstream. I thought about what an easy retrieve it would have been for Bailey, and in my mind’s eye I could see her swimming toward me with the mallard in her mouth. But I would have to be the retriever today; I couldn’t bear the thought of letting my bird—our bird—float down the river and vanish from sight and memory.

I almost made it to the duck without going over the tops of my hip boots, but the final few steps put me in deeper water, and I felt the shock of freezing river water beginning to fill my boots. I had the drake now, and if I was 20 years younger—or even 10—I would have laughed off the situation as a minor misadventure. But I knew that at age 80, with arthritis in my lower back and two knee replacements, struggling back to the bank with boots full of water might not be so easy. It wasn’t, and by the time I’d fought the current and flopped on shore, I felt like I had run a marathon.

With darkness falling, the temperature dropped well below freezing. Shedding my gloves to struggle out of my boots, empty them, and wring out my socks left me with numb fingers and visions of hypothermia. My legs, long johns, and pants were soaking wet, and I knew the slog through the snow back to the truck with duck and gun in tow would be a serious test of will and endurance. I took it slow, stopping often to catch my breath. I wanted to sit down in the snow to rest, but I knew that was a bad idea. After what seemed like an eternity, I made it to the truck, more exhausted than I ever remembered being.

When I got home an hour later I ate a bowl of hot soup and crawled into bed, thinking I’d feel better in the morning. The truth is I didn’t feel too chipper for several days after my involuntary dip in the river, but to my great relief I hadn’t had a heart attack or caught pneumonia.

Despite my ordeal, I don’t plan to give up the sport I’ve loved for most of my life, even though I’m without a retriever for the first time in almost 50 years. I have friends who have dogs, and I have a duck boat I can use for retrieving chores while hunting over water. I may yet get another dog, although taking on that kind of commitment and responsibility at my age will require some serious soul-searching.

The HIP survey is good for waterfowl conservation and something I fully support. But every bird taken by a hunter is a story that can’t be told by numbers in a computer. Harvest data can’t reflect the beauty of a sunrise, the smell of decaying vegetation in a duck marsh, or the hissing music of a flock of teal flashing low over the decoys. The data can’t capture the pride and excitement in the eyes of a young boy or girl who has shot his or her first duck. The data can’t show the passion, grace, and athleticism of a retriever born and bred to bring in ducks and geese. And all the statistics in the world can’t tell the story of an old man’s misty-eyed good-bye to a faithful canine friend. Some things are matters for the heart.

In retrospect, I probably shouldn’t have shot that mallard or tried to retrieve it, but duck hunters have often been known to do things they shouldn’t do. Just one mallard can sometimes make a season. At least it did for me.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy