The American Duck Hunter

A look back at key trends in waterfowling over the past 65 years, and what they might mean for the future of the resource and our hunting traditions

A look back at key trends in waterfowling over the past 65 years, and what they might mean for the future of the resource and our hunting traditions

By Mark Petrie, PhD, Dale D. Humburg, and Greg Soulliere

THE EXPERIENCES THAT DRAW US TO DUCK HUNTING ARE TIMELESS. OPENING DAY RITUALS. THE SOUND OF WINGS BEFORE DAWN. A BREAKFAST COOKED IN THE BLIND. AN IMPOSSIBLE RETRIEVE. FELLOWSHIP. SOLITUDE. YET, MANY THINGS ABOUT OUR SPORT ARE CHANGING. SOME OF THOSE CHANGES CAN BE FOUND IN THE HARD STATISTICS OF WATERFOWL MANAGEMENT, BUT OTHERS LIE OUTSIDE THE BOUNDARIES OF MERE NUMBERS. WATERFOWL HUNTING HAS EVOLVED, INCLUDING THE TACTICS WE USE, THE GEAR WE CHOOSE, AND THE PLACES WHERE WE BUILD OUR BLINDS.

WE DECIDED TO EXPLORE SOME OF THE CHANGES THAT HAVE OCCURRED IN AMERICAN DUCK HUNTING SINCE THE 1950SA DECADE THAT GAVE RISE TO MODERN WATERFOWL MANAGEMENT. IN THIS FIRST ARTICLE OF A TWO-PART SERIES, WE'LL EXAMINE SOME OF THESE CHANGES AS THEY RELATE TO THE WATERFOWL HUNTING COMMUNITY AS A WHOLE, PARTICULARLY HUNTER NUMBERS AND DUCK HARVESTS. IN THE SECOND ARTICLE, WE'LL DRILL DOWN INTO THE EXPERIENCES OF INDIVIDUAL HUNTERS AND HOW THE SPORT HAS CHANGED SINCE OUR FATHERS' AND GRANDFATHERS' TIMES.

Photo Ed Wall Media

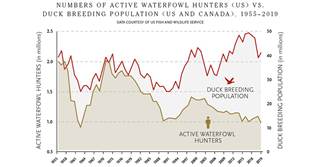

Perhaps no aspect of the waterfowl hunting community is more important than its size. Over the past 65 years the number of duck hunters in the United States has declined by half. In 1955, 2 million Americans were roaming the marshes and fields in hip boots, wool, and waxed cotton. By 2020, only a million licenses were sold nationwide. What happened to all those duck hunters?

While there is not a single answer, the ebb and flow of hunter numbers since 1955 offers some clues. In the mid-1950s, both duck populations and hunter numbers were at high levels. However, by the early 1960s duck populations had plummeted to record lows as drought withered the prairie breeding grounds. In less than a decade, license sales fell by 50 percent. As duck populations recovered in the late 1960s so too did hunter numbers. By the early 1970s duck populations were again at the levels of the mid-1950s, and 2 million waterfowlers were once again actively pursuing ducks and geese in the United States. The cyclical relationship between duck numbers and duck hunters was not only still intact, it shaped the expectations of waterfowl managers for the next 40 years.

Waterfowl populations and harvest regulations have always been closely tied to wet and dry weather cycles in the Prairie Pothole Region. Duck production typically soars when small seasonal wetlands are abundant on the prairie landscape and declines during times of drought.

Photo Craig Bihrle

The fact that we could shed and regain a million duck hunters in such a short period of time is remarkable, but what exactly do such dramatic changes in participation reveal? Hunters are sometimes categorized as either "casual" or "avid." From the 1950s through the 1990s, a good chunk of the waterfowl hunting community bought a license only when there was good news from the breeding grounds and regulations promised a long season and generous bag limits. One explanation was that those were casual hunters who came back to the sport in good years.

While it is tempting to categorize waterfowlers as either casual or avid, a study of migratory bird hunters in the Central and Mississippi Flyways by Katherine Graham at the University of Nebraska suggests that the picture is more complicated. Using electronic data now collected in most states, she was able to track how frequently individuals purchased a hunting license over time (hunters were identified by an anonymous number, not a name). Her research demonstrated that the number of active waterfowlers in a single year is considerably less than the total population of those who participate in waterfowl hunting over the course of several years. For example, in one typical state 70,000 unique individuals purchased waterfowl hunting licenses during an eight-year span. However, the total number of waterfowl licenses sold in any single year peaked at roughly half that. The larger population of waterfowl hunters contained a diverse mix of people who varied in how frequently they purchased licenses. Some hunters did so every year, while others bought licenses only once or intermittently over several years.

Photo Dean Pearson

Graham's study suggests that classifying hunters as either casual or avid doesn't accurately describe much of the duck hunting community. Many hunters regularly leave and re-enter the sport through a process called "churn." The avid hunter certainly exists, as does the casual hunter. The former buys a license every year, while the latter may go several years without buying a license. But most duck hunters fall somewhere in between these extremes.

Let's begin with 1962. That year, severe drought on the prairies resulted in the most restrictive regulations in the history of waterfowl management in the United States. In the Mississippi and Central Flyways, hunters were given only a 25-day season and a two-bird daily bag limit. All told, just over 900,000 waterfowl hunting licenses were sold that year. Given those exceptionally restrictive regulations, it would be safe to assume that most of those who bought licenses in 1962 were avid hunters.

By the early 1970s hunter numbers had rebounded to the 2 million mark as duck populations recovered and regulations were liberalized. Somewhere around a million of those hunters were likely true avids who hunted every year, while the rest hunted less frequently to varying degrees. Who were those less-frequent hunters and what motivated them to return to the fold?

Photo GARYKRAMER.NET

Some were casual hunters, who hunted sporadically, such as when they were invited by other hunters. But Graham's research suggests that many occupied another category. These waterfowlers hunt more consistently than casual hunters in years of large duck populations and liberal hunting regulations but are more likely to drop out than avid hunters when conditions are poor. We will call them "almost avid" hunters for lack of a better description.

The rapid rise in the number of duck hunters during the late 1960s and early 1970s suggests that many almost avids had come back to the sport. In those days, the average duck hunter was born in the 1930s or 1940s, when far more Americans were raised on farms or were more closely connected to rural life than today. That kind of background encourages hunting and often provides ready access to hunting land. It is safe to assume that even among those who had moved to the city, getting back into waterfowl hunting was relatively easy given their connections to rural communities. Consequently, a large population of almost avid hunters was waiting in the wings. All they needed was some good news from the breeding grounds to renew their interest.

Drought returned to the breeding grounds with a vengeance during the 1980s, and duck populations again declined. Hunter numbers declined too, but they never dipped below a million. The base of avid hunters seemed to be holding.

The 1990s brought rain to the prairies, record duck numbers, and the most liberal regulations in recent memory. If history were any guide, we would have expected numbers of active waterfowl hunters to once again return to levels of the 1970s. But license sales topped out at 1.4 million during the 1990s, well below previous peaks. Many factors were undoubtedly at play, but increasing urbanization and declining numbers of Americans with rural roots may have depleted the ranks of our almost avid hunters. Moreover, competing interests may have reduced the pool of more casual waterfowlers, who had also bolstered license sales in the past.

The number of active waterfowlers in the United States closely tracked duck breeding populations until the early 2000s, when hunter numbers began to gradually decline despite an abundance of ducks.

If the 1990s suggested a break in the predictable relationship between duck populations and hunter numbers, the last 20 years confirmed it. Although most duck populations have remained healthyreaching a record high in the traditional survey area in 2015hunter numbers have continued to decline, albeit gradually. Two trends appear to be at play. A recent look at churn rates suggests that hunters are buying licenses less frequently, meaning our casual hunters may be getting even more casual or dropping out entirely. Unfortunately, we appear to be losing avid hunters too. The average age of the American duck hunter has been increasing and is nearing 50, and one in five duck hunters is now over 60. Participation in hunting drops off sharply after 70. We may now be entering a period of net loss, where all waterfowlerscasual and avid alikeare being lost at rates greater than they are being replaced.

The erosion of our avid base is especially worrisome as these older, more experienced hunters often serve as mentors for beginning waterfowlers. Avid hunters also provide crucial support for waterfowl conservation and management by serving as DU volunteers and major donors, managing habitat on private lands, buying licenses and duck stamps every year, and purchasing shotguns, ammunition, and other sporting goods. Ominously, the spring of 2021 brought widespread drought to the Canadian and US prairies in a way not seen since the 1980s. If past experience holds, this could result in a further decline in waterfowl hunter numbers, especially if more restrictive harvest regulations are implemented in the years ahead.

Photo Todd J. Steele

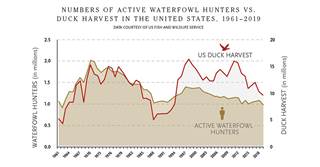

We also examined trends in duck harvests to determine if hunter numbers have tracked with changes in harvest. In 1961, the US Fish and Wildlife Service began collecting harvest statistics by species, flyway, and state. The early 1960s were a time of both severe prairie drought and exceptionally restrictive hunting regulations. So it isn't surprising that in 1962 only 4 million birds were harvested nationwidethe smallest harvest on record. However, duck harvests rose sharply later that decade as water returned to the prairies and season lengths and bag limits were liberalized. In 1970, American duck hunters bagged more than 15 million birds. In just eight years the harvest had nearly quadrupled, a remarkable testament to the explosive nature of duck populations when habitat conditions are favorable on the prairies.

Hunter numbers and duck harvests continued to track closely throughout the 1970s. When drought returned to the prairies during the 1980s, shrinking duck populations, restrictive regulations, and fewer hunters in the marsh yielded predictably smaller harvests. Through all of this, the relationship between hunter numbers and duck harvests remained tight.

Photo Ed Wall Media

Enter the 1990s. As we saw earlier, hunter numbers rose throughout the decade as duck populations recovered, but not to the same degree as during the 1970s and 1950s. Nevertheless, duck harvests soared during the '90s despite fewer active hunters. The Mississippi Flyway led the way with harvest levels well above those of the '70s. Although the most liberal regulations in 40 years undoubtedly played a role in the large harvest numbers, were changes in the hunting community also at play? On average, avid hunters harvest more birds than do casual hunters. And now, with less competition in the marsh, had they become even more successful than their avid predecessors?

In the early 2000s we began to turn a corner, but not in a good way. Over the past 20 years, most duck populations have remained at healthy levels and liberal regulations frameworks have been kept in place. Despite this good news, hunter numbers have declined, and there is some evidence that collectively, hunters are spending fewer days afield. Whether this is related to an aging hunting population or other factors is unknown, but the result has been a significant decline in duck harvests. In fact, the duck harvest in the United States has fallen about 30 percent during the past decade, with much of the shortfall occurring in the Mississippi Flyway. Fewer hunters hunting fewer days may explain some of the decline, but a recent string of mild winters may have also played a role. Warmer weather can pose a challenge for hunters at any latitude, but it may be an especially important factor on traditional wintering areas. To what extent recent weather trends have altered duck distribution and impacted hunting success and harvests warrants further study, as do other possible factors.

Hunter numbers and harvests aligned closely until the late 1980s, when the hunter success rate tailed off during restrictive seasons. The average number of ducks harvested per hunter increased to almost twice the historic rate after liberal seasons were reinstated in the mid-1990s.

Few waterfowl biologists would have predicted that we would have large duck populations and liberal harvest regulations for 25 consecutive years. But that's what we've seen since the mid-1990s. Hunter numbers recoveredat least initiallybut have since declined despite consistently large continental duck populations and abundant hunting opportunities. Reasons for the decline in hunters are not clear, but the waterfowl community should be concerned about their dwindling ranks.

DU members have been taking up the challenges of waterfowl conservation since 1937, and maintaining a large base of duck hunters may be among our greatest challenges yet. Many of today's waterfowlers have never experienced restrictive hunting regulations, and the impacts of the current prairie drought may come as an unwelcome surprise, especially if the dry cycle lasts into next year or longer. If the decline in hunter numbers accelerates in response to smaller duck populations and restrictive regulations, long-term support for wetlands and waterfowl conservation might erode as well.

Regardless of the prospects for the coming season, now is hardly the time to consider selling your duck boat and decoys. History shows that water will return to the prairies, duck populations will recover, and hunting opportunities will improve. That's why it's important for waterfowlers to take the long view and continue to huntand support conservationeven in the leanest of years. The ducks and our waterfowl hunting traditions depend on it.

Photo Todd J. Steele

Dr. Mark Petrie is director of conservation planning in DU's Western Region. Before his retirement, Dale Humburg served as DU's chief scientist and senior science advisor. Greg Soulliere is regional science coordinator for the Upper Mississippi/Great Lakes Joint Venture. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy