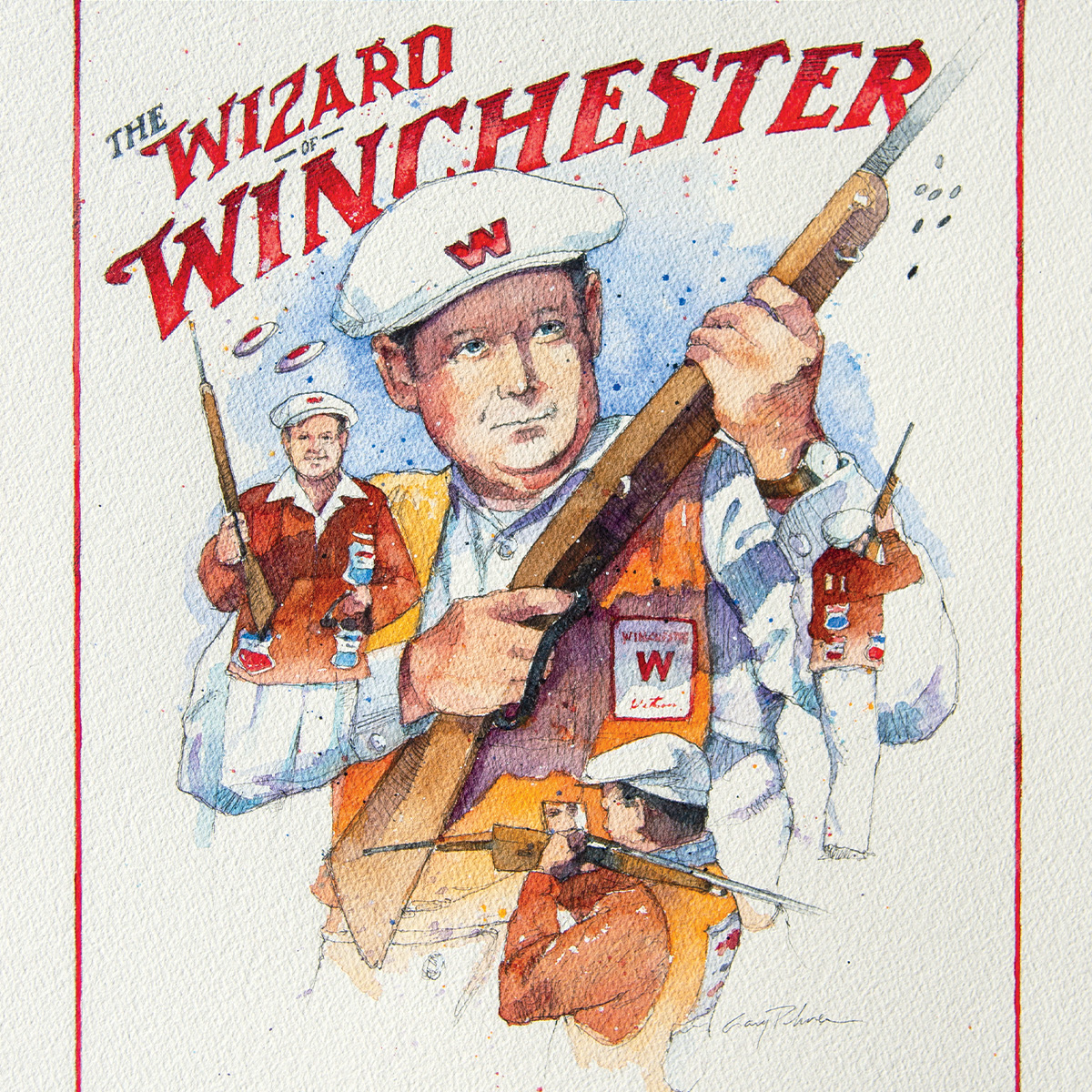

The Wizard of Winchester

Admired and respected by thousands of friends and fans, the legendary Herb Parsons was much more than just a showman shooter

Admired and respected by thousands of friends and fans, the legendary Herb Parsons was much more than just a showman shooter

By Chris Madson

I must have been about nine when Dad signed me up for the introductory shooting course that Winchester Arms offered to the children of its employees. Every Saturday morning, he’d deliver me to the range, where I’d explore all the ways a tack-driving .22 could be made to miss the bull’s-eye on a standard 50-foot NRA target.

The instructors told us that shooting a rifle is a straightforward, mechanical, strictly rational procedure requiring coordination of hand, eye, and breath. Lying there on my stomach, Saturday after Saturday, I started to understand that the mechanics were a necessary part of the process, but not the only part. I realized that marksmanship is also a metaphysical exercise, a Zen thing. For most humans, it requires stern discipline and years of practice. It is a skill that can be improved but never really mastered. And for a lucky handful of shooters, it’s a gift.

One Saturday that summer, the folks at Winchester invited the public out to Nilo Farms, the company’s demonstration hunting preserve, for an hour of entertainment by Herb Parsons, Winchester’s showman shooter. Dad and I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. As things turned out, it was one of Parsons’s last exhibitions, but he was in superb form, both with his shooting and the inimitable Parsons patter.

Herb Parsons thrived as much behind the microphone as he did behind the gun, captivating audiences with his rapid-fire monologue.

I don’t remember the details of all the shots he made that day. There was the famous routine in which he’d throw a whole stack of clay targets in the air and then break one at a time with a Model 12 pump gun before they hit the ground. He held the unofficial world record at the time: seven targets powdered as they fell. I can’t remember how many he broke that afternoon—five, six, seven maybe. It was a bunch, and in his hands that pump gun cycled shells faster than a semiauto. Throughout his show, Parsons demonstrated what he could do using rifles and shotguns from the Winchester lineup. He shot a watermelon, then a head of cabbage: “Now, here’s the quick way to make yer coleslaw!” he said through his thick Tennessee drawl. Then an orange and a walnut and an aspirin tablet that disappeared in a puff of white dust.

But the shot that left me wide-eyed and slack-jawed was the one with the washer—a thin metal disc about the size of a silver dollar with a hole in the middle that was not much more than half an inch across. After Parsons had worked his way down from the watermelon to the aspirin, he picked up a slim .22 semiautomatic rifle and fed a few rounds into the magazine while he kept up his rapid-fire monologue.

“Now, one more thing. I’m gonna flip this washer up in the aar,” he said, “and shoot rat through this here hole. Now, watch close!” He threw the washer 30 feet into the air like he was flipping a coin. The rifle came up in one fluid motion. There was the crack of the shot as the washer reached its apex, and he walked over to pick it up.

“Thar,” he continued as he held it up. “See that? Not a mark on ’er. Right through the middle!” Then he paused and looked at the audience with a frown.

“Now, I kin see that some a you folks don’t think I shot through that hole. You ain’t believin’ me. And that hurts me. It truly does.” And he shook his head in disappointment.

Herb Parsons’s exhibitions were promoted nationwide, drawing legions of fans who were eager to see the “Wizard of Winchester.”

“So, fer all you doubters, I tell ya what I’m gonna do.” He walked over to the table where he kept all his guns and props and picked up a roll of masking tape. “I’m gonna stick a piece a tape over that hole and we’ll do ’er agin.” He put down the rifle, tore off a piece of tape, and, mumbling to himself about the creeping curse of cynicism in modern times, covered the hole in the washer.

“Thar now,” he said as he held it up. “Now, we’re gonna try ’er agin.” He picked up the .22, flipped the washer into the air, and took another shot. After a theatrical pause, he sauntered over to the place where the washer had landed, bent down, and looked hard at it in the grass, shaking his head again in mock disappointment. Then, as we all held our breath, he picked it up and displayed it between thumb and forefinger so we could all see the .22-caliber hole in the tape. There wasn’t even applause—for a long moment, we were struck dumb.

“Just no trust left in the world,” he said, almost to himself. “No trust.” And the applause began.

Joel Herbert Parsons was born on May 5, 1908, to James and Allie Parsons, a farming couple in Fayette County in the southwest corner of Tennessee. Fayette County’s premier cash crop in those days was cotton, but many farms were subsistence operations, a mix of livestock, poultry, corn, small grains, potatoes, and pasture designed to feed a family and turn a profit. The small fields, woodlots, pastures, and brushy fencerows combined with the wild river bottoms to offer excellent habitat for a variety of small game. It was a good place for a boy with an interest in shooting to grow up.

Like most farm kids of that time, Parsons grew up with a rifle in his hand. When he was seven, as he told reporters many years later, he killed a bobwhite quail on the wing with his single-shot .22, the first sign that his marksmanship might be something out of the ordinary. Not long after, his parents moved to nearby Somerville and opened a boarding house so he and his sister could step up from the one-room country school they’d been attending.

Parsons prospered in town, playing center on the high school football team and throwing shot put for the track squad when he wasn’t cruising the woods with a .22 or a shotgun. During his junior year, a pair of visitors came to town who would change his life.

The Toepperweins thrilled audiences with marksmanship feats and inspired a young Parsons to follow in their footsteps.

Trick-shot demonstrations attracted big crowds.

Ad Toepperwein made his reputation as an exhibition shooter with the Orrin Brothers Circus in the last decade of the 19th century. Impressed by the crowds he attracted, executives with Winchester Repeating Arms hired him, along with his wife, Elizabeth “Plinky” Toepperwein, to drum up business for the company.

The “Famous Toepperweins” rolled into Somerville in 1926. Ad extinguished lit matches with a rifle, split playing cards edgewise, and broke targets behind him, using a mirror to aim with the rifle pointed backwards over his shoulder. Plinky shot small wooden blocks out of the air with a .22. The young Parsons was enthralled. According to his son Jerry, he decided on the spot that he wanted to follow in Toepperwein’s footsteps.

At the time, it was a far-fetched goal. Parsons graduated from Fayette County High School in the spring of 1927 with 16 other young scholars and spent the next three years working for a local grocery wholesaler. With the stock market crash in 1929, a blight settled over the country. It took a marvelous turn of luck to get him out of the warehouse and on his way to fame.

A district salesman for Winchester who stopped over in Somerville wanted to do a little hunting, and some unremembered resident suggested that he should go out with Parsons. The man was highly impressed and later mentioned his young guide to Winchester’s district managers. Shortly thereafter, with the Great Depression deepening, Parsons landed a job as a salesman for Winchester.

He joined the company just before it went into receivership, following a decade of largely failed experiments with a wide variety of product lines, from lawn mowers and tires to refrigerators and washing machines. Parsons found himself selling rust remover, roller skates, and kitchen knives as well as guns and ammunition as the business struggled with the dual challenges of reorganization and the national economic malaise. With a genuine affection for people and a gift for conversation, he was a natural salesman. In 1934, his manager challenged other salesmen in the district to keep up: “Herbert Parsons is high man on flashlights having sold 1,588,” the manager wrote, “and is also high man on batteries having sold 848 dozen.”

Shown above is Parsons’s own Winchester Model 21, his favored competition gun, which is displayed along with other memorabilia at DU national headquarters in Memphis.

When it came to selling guns and ammunition, Parsons was inclined to follow Ad Toepperwein’s example. He figured the best way to get people to buy was to show off the product with fancy shooting. The bosses seemed to think otherwise. Later in 1934, his district manager wrote: “You are not supposed to attend any shoots of any kind outside your territory . . . should the company ever desire to have you attend a shoot . . . either the company or I will advise you.” He congratulated Parsons on his sales of the new .410 Model 42 pump, one of the classic Winchesters of that era, but cautioned him to “bear down on cutlery, flashlights, and batteries.” Another executive reminded him that “there is no profit in winning titles—there is in selling shells—and in the final analysis that’s what you and I get paid for.” As late as 1936, a sales manager admonished him: “You are essentially a Winchester salesman and not a shooting artist . . . and we cannot help but feel that your sales work is more important.”

While the corporate leaders were slow to recognize what they had in Parsons, the Winchester people out in the real world began to appreciate his practical value. Remington-Peters was paying the husband-and-wife team of Ken and Blanche Beegle, along with “Captain” M.E. Hicks (a figure now lost to history), to show the Remington brand around the Southeast, and their efforts were bearing fruit.

“Peters Cartridge Company is gaining volume in North Carolina rapidly, and due almost entirely to Mr. Hicks’ exhibition shooting,” one district rep wrote in 1938. The antidote, he continued, was Herb Parsons. “Everywhere Mr. Parsons gave an exhibition we were told that we had larger crowds than did either Mr. Hicks or Mr. Beegle; that his shooting was better, snappier and much more entertaining. I realize that exhibition shooting is very expensive; also that it is very effective.”

Three years later, another district manager agreed: “Our competitors have been using Hicks and Beagle [sic] in this territory and have switched a lot of our business during the last ten years.” The answer, he continued, was to push back with something even better. “Parsons has a very pleasant way of handling the crowd, and the dealers. I am quite sure that if you could see his exhibition, and see the effect it has upon the dealers and consumers that witness it you would feel the same about it as I do. This boy really has a show that you should see.”

It’s hard to believe that, after 10 years of Parsons’s steadily increasing notoriety, the higher-ups hadn’t bothered to take in a single one of his performances, but, by 1940, even the bosses were beginning to understand how important his shooting was to the company’s image and sales. By the summer of 1942, he was handling a hectic schedule of exhibitions from coast to coast; soon after, he joined the US Army and spent the next three years teaching thousands of pilots and aerial gunners how to hit a moving target with a shotgun, “sharing his knowledge of deflection shooting with these students,” according to one commanding officer.

On July 17, 1945, Parsons mustered out of the army and resumed his career with Winchester. By that time, he was easily the best-known shooter of the era, which is probably why he was asked to do the fancy shooting in Jimmy Stewart’s landmark western Winchester ’73 in 1950. That was in the days before CGI, when Howard Hill, the world-famous archer, actually split arrows during production of Errol Flynn’s The Adventures of Robin Hood.

Actor Jimmy Stewart and Herb Parsons during the production of the Hollywood western Winchester ’73.

There’s a shooting contest at the beginning of Winchester ’73 that features some great footage of bullet holes appearing in the bull’s-eyes of targets, and a sequence where Jimmy Stewart and his opponent shoot coins out of the air. Finally, there’s the shot that wins the contest—Will Geer (in the role of Wyatt Earp) throws a quarter-sized washer into the air for Stewart to hit. Stewart fires as it starts to drop.

“Miss!” Geer announces to the crowd as he picks up the disc.

“It was my mistake,” Stewart replies. “I shot right through it.” The crowd laughs. Stewart borrows a postage stamp, sticks it over the hole in the washer, and says, “I’ll do it again if you want.”

Geer flips the disc into the air, Stewart fires, and Geer walks over to pick it up as the crowd holds its breath. There’s a hole through the stamp. All that shooting was the real thing—no tricks, no Hollywood sleight of hand, just Herb Parsons there to make Jimmy Stewart look good.

It was the beginning of Parsons’s transition from notoriety to national fame. As the decade proceeded, he appeared on NBC’s Today show; he was featured in articles in True and Look magazines; he hobnobbed with Clark Gable, Wallace Beery, Roy Rogers, and Ted Williams; he staged exhibitions at Disneyland and toured American military bases in the Far East. Tens of thousands of people flocked to see him. They started calling him the “Wizard of Winchester.”

Parsons with his wife and their two sons.

The schedule was grueling, but now and then he managed to find time to shoot in traditional shotgun competitions for score instead of entertainment, something exhibition shooters had avoided since Annie Oakley’s time. In 1934, he complained to his boss that he’d lost the Mississippi state trapshooting championship by a single bird. In 1942, he won the Grand Pacific handicap trap event with 199 out of 200 targets. In 1948, he won the state trap and skeet titles in Texas, breaking 298 out of 300 skeet targets, then claimed the Grand Pacific trap title again with 399 out of 400. In 1953, he won the professional class at the Grand American and followed up the next year by taking the handicap event. No flashy tricks, no Parsons line of patter, just grinding targets, usually with a Winchester Model 21 side-by-side.

His hunting credentials were almost as impressive as his shooting. In 1949, he won the International Duck Calling Championship and went on to win the World’s Championship in Stuttgart, Arkansas, in 1950 and 1951 before retiring from the contests to judge the competition in subsequent years.

Beyond the records and the crowds, what stands out in Herb Parsons’s career are the friends. He never lost his Tennessee modesty, even after decades of cheering crowds, and he took a genuine interest in people. There was a warmth about him that touched everyone he met. A loving husband and doting father, he held his family together even though his work called him away for weeks, or even months, at a time. He was a good man.

Parsons claimed the International Duck Calling Championship in 1949 before back-to-back World’s titles in 1950 and 1951.

In the spring of 1952, Parsons collapsed during a demonstration in front of 8,000 people. He was 44 years old. At the time, doctors found nothing more serious than stress, slightly elevated blood pressure, sky-high cholesterol, and about 25 pounds of tallow he needed to drop, a medical description that would have fit a large percentage of middle-aged men at the time.

Late in 1958, he was feeling poorly again. In July of 1959, physicians recommended surgery to repair a hernia in his diaphragm. During the surgery he apparently had a minor heart attack, followed by two others over the next several hours. He died in Memphis, Tennessee, on July 19 at the age of 51.

Legendary outdoor writer and fellow Tennessean Nash Buckingham shared a great respect for Parsons.

The condolences rolled in, from governors and senators, generals and corporate moguls, colleagues and thousands of friends. Nash Buckingham, Tennessee’s venerated outdoor scribe, had been around long enough to put Parsons’s career in perspective:

“From the vantage point of eighty years, I have known and watched all the shooting ‘greats:’ Annie Oakley; Buffalo Bill; his protégé, young Johnny Baker; Dr. Carson; Mr. Bogardus; Mr. & Mrs. Toepperwein; Osa and Martin Johnson. But Herb put into his work something that surpassed skill and dealt with instructive, constructive principles of character.”

A friend in Memphis spoke for many when he wrote to the bereaved family: “It has been so truly said that the final measure of a man’s service is not in what he accumulates, but in how much of himself he leaves behind. By this measure Herb Parsons stands exceedingly tall. His life, as we view it now, resolved from the possession and use of many qualities, all of which spring from a greatness of spirit. Herb Parsons was one of the finest men I have known. His life was a great revelation, a positive message of living so humble and outreaching that it touched many people in many places.”

I remember standing in the crowd that sunny afternoon so many years ago when the Wizard of Winchester showed us how the impossible was really possible. What I remember most wasn’t the shooting but the talking, the rapid-fire patter that left us all smiling and, at the same time, thinking a few things over. Parsons drew a fine bead, as they say down in Tennessee, and what he said, who he was, went straight to the heart.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy