Decoys and the Characters Who Use Them

You can understand a lot about waterfowlers by the way they set their spreads

You can understand a lot about waterfowlers by the way they set their spreads

By Doug Larsen

It may seem unfair of me to carve up our nation’s close-knit population of waterfowl hunters into specific categories. But I find the exercise to be quite entertaining, so that is what I am about to do. Lumping people into types helps me understand more about a person’s various skills and interests, and if I have learned one thing in four decades of hunting, it is that we should never stop growing our knowledge base and never stop trying new things. In the meantime, humor me as I categorize hunters by their decoy-related idiosyncrasies. Don’t be surprised if you recognize yourself or some of your hunting buddies in one or more of these—I see at least a little bit of myself in there too.

This decoy archetype probably originated with leave-them-out-all-season rice-field hunters in Missouri and Arkansas. The Duck Super Spreader maintains a floating duck rig that he hopes will someday appear on a Google Earth image. Consisting of hundreds of mallards and pintails with dozens of teal and geese sprinkled in, his spread resembles relaxed ducks on a rest area. This is somewhat sensible if it is a permanent spread, but some Super Spreaders have adapted their voluminous rigs for the road. The work involved in the daily deployment of a spread like this resembles the bend-and-stoop farm labor described in The Grapes of Wrath, with a several-hour break period included to actually hunt ducks. The Super Spreader believes in his heart that if you want to decoy big flocks, you must show the ducks big flocks, and spreads this large are a common strategy of hunters who would rather hunt traffic ducks than hunt right on the X. To handle these gargantuan rigs, a boat must be big—think deep-V big, Great Lakes big, and approaching offshore-fishing big. In addition, the Super Spreader’s hunting buddies must drink the Kool-Aid of the big-spread doctrine. Otherwise, after a hunt or two they become exhausted from feeling like they work in an extension cord factory, wrapping decoys until they wear the sleeves off of their shirts.

Often residing in the upper Midwest, the Perfectionist has never hunted with a lot of decoys. He hunts out of a hand-me-down Lund Ducker, and there is only room in the boat for him, about a dozen decoys, and a 100-pound chocolate Lab. Because he hunts with so few decoys, he insists that they be perfect. He normally sets out six mallards and six other decoys, which may include wood ducks, wigeon, and ringnecks. He doesn’t like using ringneck decoys, but the darned things are all over the place up there, and a guy has to match the hatch. At one time the Perfectionist spent much of his off-season calling the customer service hotline at a certain decoy manufacturer to express his concerns about paint overspray, and he dreams of the day that some company will produce a good storm wigeon. These days the Perfectionist is happier than ever, because he feels that flocking has been one of the greatest advancements since the electronic duck stamp—he calls it “magic duck velvet.” If his flocking rubs off even a little, he replaces it using glue and tiny tweezers.

Like the Perfectionist, the Traditionalist hunts with a small spread, but he would rather stay home and paint a mile of wood fence than hunt over a plastic decoy. It’s hand-carved wood or cork only for him, decorated in oil paint thinned with linseed oil. When the Mack’s Prairie Wings catalog arrives at the Traditionalist’s home, he tears the decoy pages out straightaway, lest he be exposed to any of that “plastic profanity.” The Traditionalist is an accomplished woodworker, but instead of building cuckoo clocks or carousel horses, he focuses on decoys, and he often hunts over an award-winning hooded merganser and a hollow swan confidence decoy, though he has no plans to shoot the birds that these decoys represent. At decoy get-togethers, he often boasts to other Traditionalists that he exchanges holiday cards with a legendary carver, and they usually respond with a jealous little gasp.

The Economist is something of a misnomer. Adam Smith was an economist, but the person I am talking about here is more of an Economizer. He loves to hunt big spreads, and he enjoys hunting over decoys, but he never buys a decoy unless he can find it at a closeout price or at a garage sale. Many of his decoys didn’t cost him a dime, because he found them abandoned in a ditch or floating happily along a lonely lakeshore.

Many Economists are from the Mid-South, where big decoy spreads are often the order of the day. Several years ago, an Economist came upon a decoy bag on the side of the road outside Paragould, Arkansas. Lo and behold, it was full of almost-new Higdon floating mallards. The bag had clearly bounced out of someone’s boat. After the Economist made a halfhearted attempt at returning the decoys via Facebook, he happily added them to his personal spread. If the Economist’s rig looks like a cobbled-together dog’s breakfast of a decoy spread, that’s because it is, with heavy emphasis toward value and just a little tilt toward being a duck attractor. Like Geppetto, the Economist tinkers with all the decoys he finds, adding house paint and filling holes and cracks with caulk and epoxy. All the decoys he owns are rigged with six feet of knotted string trimmer line and spark plugs.

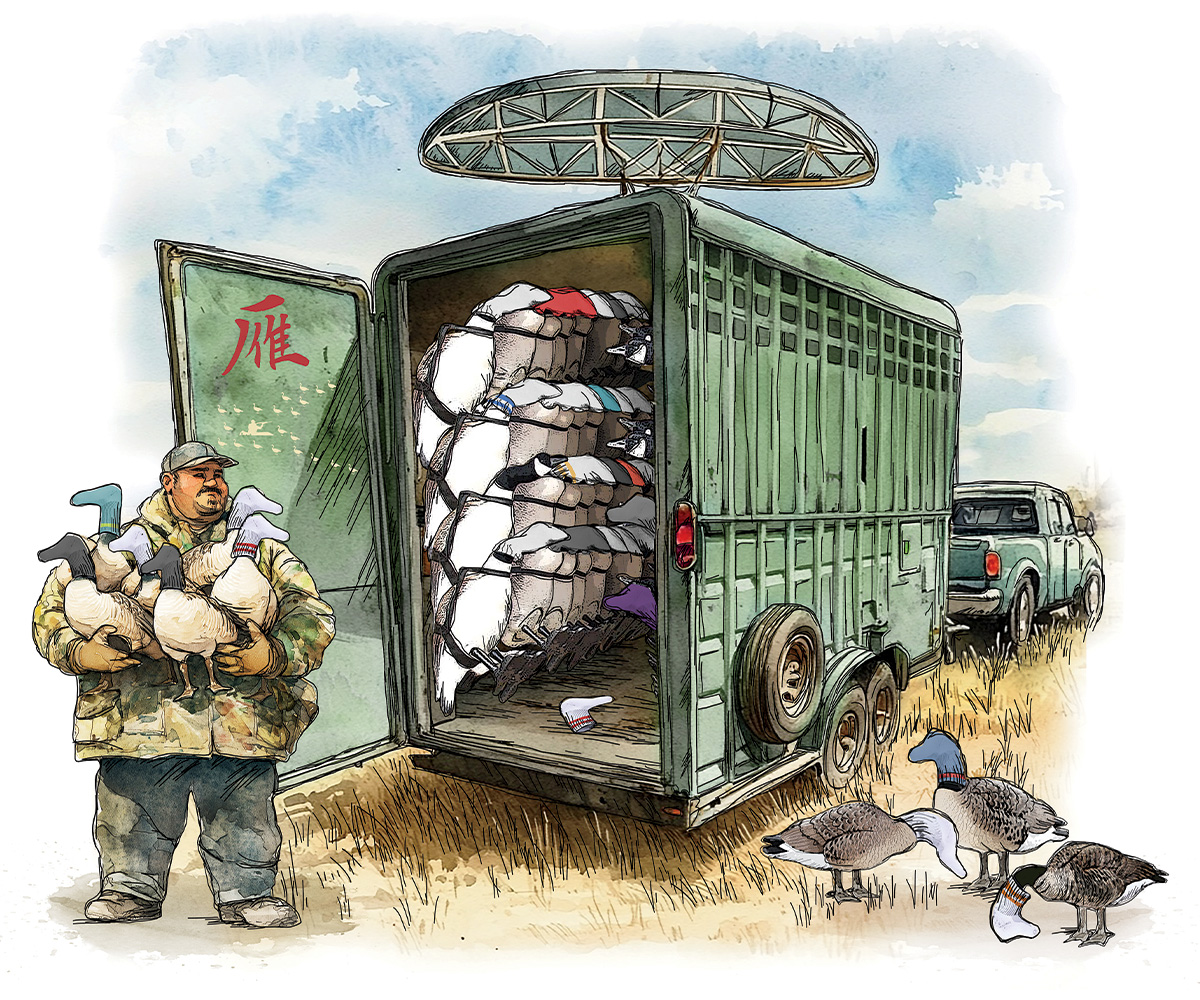

Like the massive bison herds that once roamed North America, the Goose Super Spreader travels the Great Plains in his modern-day prairie schooner, which is a three-quarter-ton truck pulling an enclosed trailer the size of a rural church. Inside this trailer is a very complex system of shelving that the Goose Super Spreader has outfitted to house a legion of full-body Canada Goose decoys that are ready to be deployed in a harvested grain field. If you are permitted to peek inside the trailer, which is akin to going behind the Oz curtain of goose hunting, you will know that the heads of all these decoys are flocked, because each one is covered with a black sleeve or an old sock. This is to protect the flocking, though I always think that it looks like each of the decoys is going to the guillotine. The Goose Super Spreader is more than willing to discuss decoy patterns, which usually involve deploying the decoys in the shape of a letter, such as X, V, or C. Sometimes, if he is feeling sassy in the pre-dawn, he will arrange his decoys in the shape of a horseshoe. If you want to mess with a Goose Super Spreader, act very secretive, and then tell him that you only set your decoys in the shape of the Chinese symbol for the word “goose,” which looks like this: 雁

The Soda Pop Kid is both thrifty and committed. Almost his entire spread, which includes many, many hundreds of decoys, is crafted from one-liter soda bottles. The Soda Pop Kid and his family and neighbors have never enjoyed even an ounce of soda from a can, because the pursuit of one-liter bottles is all- consuming. Most Soda Pop Kids originate from in and around the duck decoying mecca of western Tennessee, and Reelfoot Lake in particular, a peculiar hunting location where massive blinds and even more massive decoy spreads are the order of the duck season. If you don’t have a couple dozen G&H decoys floating in the hole, flanked by 3,000 one-liter bottles, dozens of spinning-wing decoys, and a blind with a color television and a couch, then you aren’t really trying on Reelfoot.

The only things a soda pop bottle decoy requires are a coating of tar or automotive underbody primer, a cord, and a weight. But the hardest work just might be consuming all the soda in the first place. To amass 3,000 one-liter bottles, you must find enough friends and family to drink almost 800 gallons of soda. Just typing that sentence reminds me to make a dental appointment. Anyway, emptying all those bottles is a tall order, but it will keep the Soda Pop Kid in decoys for years to come, and when you set out that many of anything that kind of looks like a duck, it works.

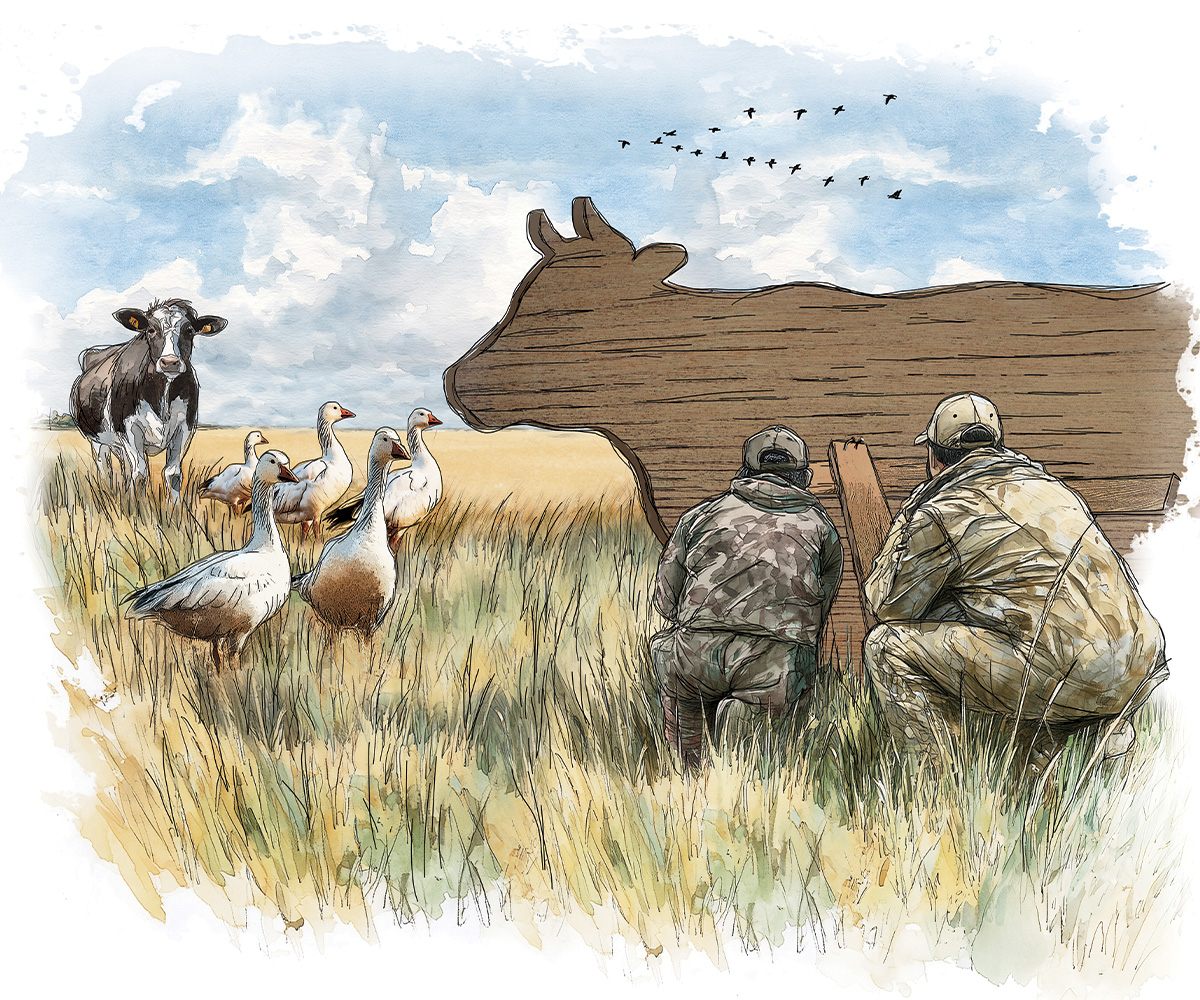

There is a small subset of hunters, mostly in the West and Midwest, who hunt with just one decoy—and that decoy is an almost full-sized likeness of a cow. If you haven’t seen these livestock decoys in the popular hunting catalogs, then you have not been going deep enough in the book. They are there, often on the same page as the herons and the swans. For those of you who are not familiar with the tactics involved in using a cow decoy, imagine that the Cowboy has found a group of geese feeding in a field. He and a buddy determine that the best way to approach the birds is by hiding behind what is essentially a two-dimensional Trojan cow. Ever . . . so . . . slowly . . . they creep along behind the cow and close the gap on the feeding geese. If they do it carefully and correctly, they will eventually be in shotgun range of the birds, who are generally not fearful of livestock. When they determine that the moment is right, the hunters push the cow to the ground, and at this point there is nothing left but the shooting. I will admit that I have never seen this done, but I did see the Three Stooges in the short film Horsing Around, and it seems similar.

Like the Cowboy, the Traveler places special importance on just one decoy, regardless of where he hunts or with whom. Most of the Travelers I have met come from the Northeast or Mid-Atlantic states, but they can be found almost anywhere. They share the practice of arriving to a buddy hunt or an invitation hunt or even a guided hunt with one special decoy. It might be a decoy that they made by hand, or a decoy that they traded or received as a gift from someone special. Their goal is to try and put as many miles on the decoy as possible.

So the decoy goes hither and yon, and the Traveler writes about the decoy’s experiences in a little book. It’s like journaling, but with waders and shotguns. In every case, the decoy has special meaning to the Traveler, and in every place the Traveler visits, when he asks if it is permissible to deploy said decoy, the genial host says, “Of course, put it out wherever you like.” The Traveler then wades out and carefully places his chosen decoy right in the middle of what most of us would call the kill hole. This is fine. It’s a perfect setup for the Traveler to snap photos and tell a story. But if you find yourself hunting with the Traveler, you’ll spend the morning trying desperately to avoid shooting his decoy. The ducks will invariably head straight for it. Maybe a lively cripple needs the coup de grâce? You guessed it, that duck will be swimming in circles around it. The last thing you want to be is the guy who patterns an ounce of steel 3s on the Traveler’s treasured decoy, so you wait patiently and do the dirty work once the coast is clear.

One thing you know for sure about the Rag Man is that he has lots of friends. His typical hunt involves putting out thousands of rags, silhouettes, and wind socks. If he didn’t have a crew of like-minded pals, he would never be able to hunt the spread. Limited almost exclusively to the pursuit of snow geese, both in the fall and during the conservation season, the Rag Man measures the size of his spread in acres, and he stores everything in a trailer that would be well suited to an automotive racing team. I recently saw a Marketplace post by a Rag Man who was on the cusp of upgrading his rig and selling his old rags. In addition to a 20-foot trailer, the post listed “700 dozen rags and windsocks.” I thought for sure that this was a typo, but it was not. This Rag Man possessed 8,400 snow goose rags.

Snow geese congregate in enormous flocks. Decades ago, 500 rags was enough to make a hunt. Then some Rag Man put out 1,000 rags, then another put out 2,000, and so on. Eventually, competition drove the size of decoy spreads up the scale until we reached a point where we think we need to deploy thousands and thousands of rag decoys. If you are kind and good and pure of heart, the field will be dry, but if in your life you have ever committed an evil deed, it will rain, requiring you to pick up 8,400 muddy rags while slogging through mud that is the consistency of pudding. Long story short, I have hunted with many Rag Men, and they can produce some amazing spectacles, but the work involved is on the order of building a pyramid.

I love these people. For the most part, they hunt in a very normal fashion. They will put out a few dozen carefully selected modern decoys. They hide very well, and they can operate a duck call with aplomb. But, in the spirit of flat-Earthers and those who believe in the powers of essential oils, Realists believe that they must create a truly relaxed atmosphere that goes beyond plain old duck decoys. In various places around their blinds or at the edges of the marsh, they will carefully place decoys that imitate a number of bird species that are noted for their cool demeanor. Most popular is the great blue heron, but they will also sometimes deploy cattle egrets, seagulls, ravens, swans, and even pigeons. Mammals are generally considered next-level confidence decoys, but I did once see a taxidermy beaver in a beaver-dam puddle-duck spread. We had a very good hunt that day, but I personally viewed the beaver as more of a mascot than a duck-attracting participant.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy