Micro-Spreads

When placed strategically, a small number of decoys can achieve big results

When placed strategically, a small number of decoys can achieve big results

It had been a frustrating morning. Several flocks of mallards swung past my spread of three dozen decoys, gained altitude, and then piled into another pond 200 yards away. While I managed to take a few teal that buzzed over my blind, the big ducks wanted nothing to do with me. By the time I took the hint, the flood of mallards had dwindled to a trickle.

Hoping it wasn’t too late, I grabbed the four closest decoys and hustled over to the pond, where I hurriedly tossed them out and tucked myself into a tall, grassy bank. It took just 10 minutes for the first greenhead to lock up on my little spread and only about 30 minutes to shoot three more before the flight finally ended for good. Those four decoys helped salvage what otherwise would have been a busted hunt.

What I learned that morning is that less can sometimes be more when it comes to decoys. Ducks and geese that have grown leery of big spreads might fall into a few well-placed dekes with no questions asked. In other situations, a small spread might more accurately represent what real birds are doing. And, of course, a few decoys are a lot easier to carry, place, and pick up than several dozen. The following waterfowlers have cracked the code of how to have consistent success with small numbers of decoys. Heed their advice and you just might enjoy similar results with a downsized spread in your area.

While hunting public land in western Missouri, Blake Boland realized long ago that he’s better off using a dozen highly realistic decoys than a larger spread of less lifelike blocks. In fact his decoys, which consist of actual duck skins mounted on polyurethane forms with floating bases, take realism to an extreme. “When I first started making these decoys,” Boland recalls, “75 percent of them were hens, and I was still out-pulling other hunters. Real feathers look natural to ducks and help convince them to finish.”

Boland notes that most hunters in his area use much larger spreads, so his 12 decoys stand out from the competition. Using a small spread also allows him to walk into areas that other hunters can’t access. He loads his decoys, shotgun, portable blind, and other gear into a sled, which he pulls behind him into shallow marshes and backwaters.

Once he reaches his hunting spot, Boland defies conventional wisdom by placing all his decoys together in one bunch. “They aren’t so close together that they bump into each other, but I think having them in a tight group helps them show up from a distance. I used to put a pair here and a pair there to look like resting ducks, but I’ve found that this setup works better and gives me more pulling power.”

Blake Boland says his small, super-realistic rig is effective because it gives the ducks a different look than all of the other decoy spreads in the area.

Boland readily admits that concealment is the most important element in his hunting success. He has used layouts and ghillie suits in the past, but now he hunts with a portable A-frame blind. He camouflages his blind with bunches of prairie cordgrass, making sure that he has plenty of overhead cover to eliminate any “black holes.” If ducks aren’t finishing, Boland checks the cover on the blind, looks for any shadows it might be casting, and repositions it if necessary.

Many of the ducks Boland sees are high, trading flocks, so he calls aggressively to get their attention. As flocks begin to circle the decoys, he adjusts his calling according to the birds’ reactions. “Some days we need to call them all the way to the water, while on others, it’s best to quiet down. Everyone likes to call so you feel like you are doing something, but at times you’re better off letting the decoys do the work,” he says.

In a region known for cackling geese, M.D. Johnson of Cathlamet, Washington, targets western Canadas, which are the biggest geese in the area. While he occasionally deploys as many as 18 full-body decoys, he mainly uses a dozen or less. In the latter parts of the season, when many geese are in pairs, he’ll reduce the size of his spread to only a few decoys. As a result, he invests in the most realistic decoys he can find and restores the flocking on them often to keep them looking good.

Regardless of whether he deploys only a few decoys or his “big” spread of 18, Johnson makes sure he’s in the right spot. “I don’t use enough decoys to run traffic. I have to be where they want to be. When you downsize your decoys, the X is a lot smaller,” he says. “You can’t be within 500 yards or 100 yards or even 100 feet. You have to be exactly where the birds are feeding or resting.”

Johnson typically hunts on pastures where geese come to loaf later in the morning after feeding in nearby grainfields. This allows him to set up in daylight, which he sees as an advantage. “In the dark, you always set decoys too close to the blind and too close together,” he says. “It’s always important to leave space between decoys, especially when you’re only using a few. Five to six feet between decoys isn’t enough. I like five to six steps, which expands my footprint.”

M.D. Johnson typically puts out less than one dozen of the most realistic decoys he can find.

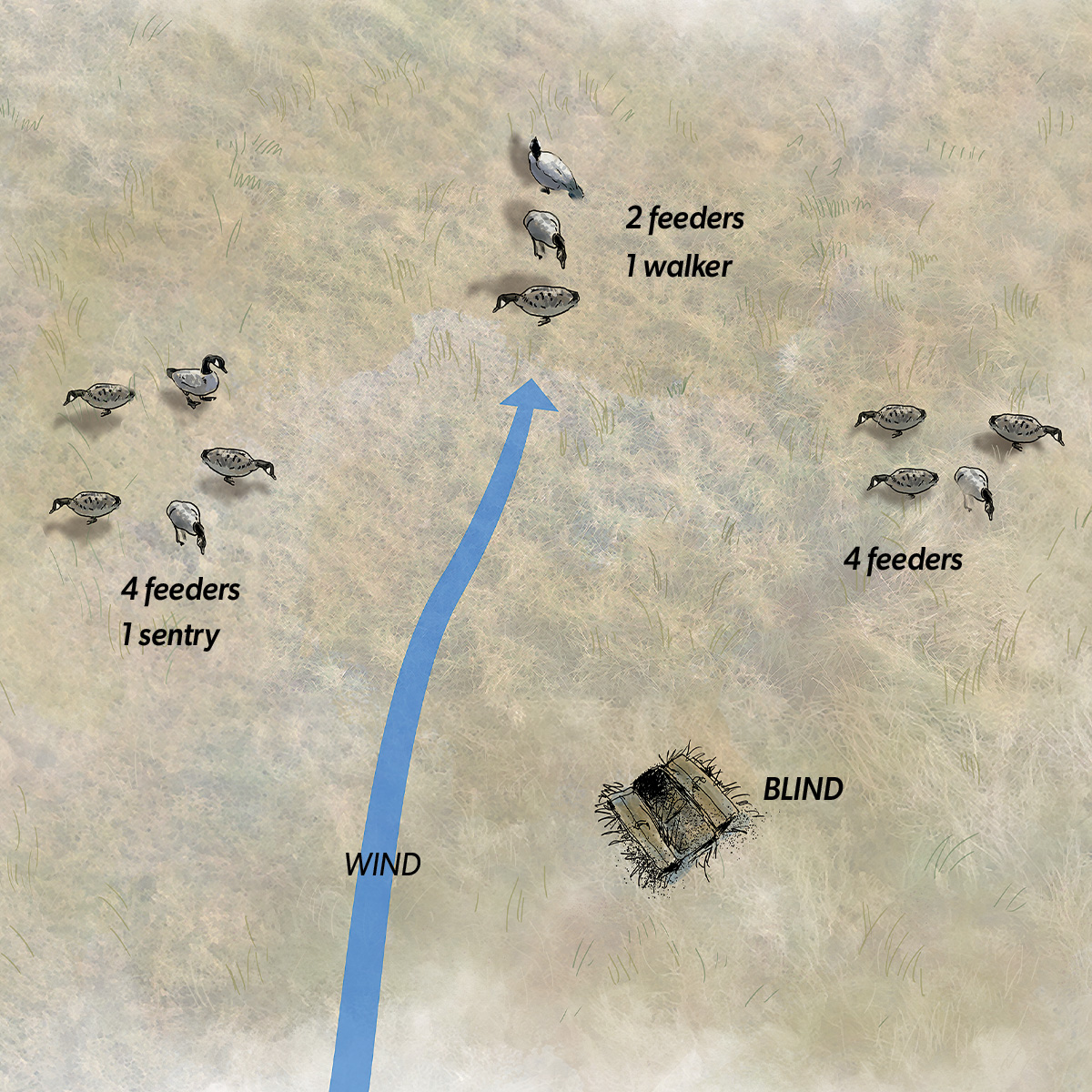

Using decoys with the right head and neck postures is another important consideration when using a small spread. “Heads up mean geese are nervous, so I use only one sentry at most,” Johnson says. “I typically set my decoys in what I call a ‘lunch line,’ where I place several feeders in a small group and then a walker that looks like a bird that has just landed and is walking over to join the group. Real birds key on that look and will often land next to them.”

One of Johnson’s favorite spread configurations consists of three small groups of decoys positioned about 30 yards downwind from his blind. For an extra touch of realism, he removes the bases on some of the decoys to imitate birds resting on their bellies. He hunts from a layout blind, which he sets against a clump of grass or other cover to help break up the outline. He also makes sure his blind is thoroughly brushed with vegetation that closely matches the surroundings. “Hiding is one thing that I can control, so I make sure to do a thorough job,” he says.

Jerry Talton hunts with small spreads because the secret to success along North Carolina’s Outer Banks is getting away from the competition, and that’s easier to do when you travel light. “You’ll see hunters parked at every access point every day of the season here,” he says. “I have to hunt places where other hunters can’t go or don’t want to go.”

A small spread packs easily into the 14-foot canoe he uses to navigate tidal creeks and sloughs. “I’m like everyone else. I have all this duck hunting gear, but over time I have pared it down to a shotgun, a pocketful of shells, two calls, and a few decoys that allow me to travel light.”

A professional decoy carver, Talton typically hunts over four to six wooden Core Sound–style blocks that he makes himself. He scouts mornings and evenings and watches birds as they follow the tides. “I’ll cut open the crops of ducks I shoot to see what they’re eating and try to locate where they are feeding,” he says.

Jerry Talton sets his simple hand-carved spread along open bends in tidal sloughs to maximize visibility.

The barrier islands Talton hunts are diverse, both in terms of habitat types and the birds that use them. Teal and wood ducks are the most numerous species, but as the season goes on, he encounters black ducks, pintails, and wigeon, as well as the occasional diving duck. He always tries to “match the hatch” by using decoys that represent the species that are most numerous in the area he hunts.

Talton says that decoy placement is the key to success when hunting with a small rig. “My duck hunting mentor taught me that the function of decoys isn’t to attract ducks; it’s to control where ducks land,” he says.

Talton’s ideal hunting spot is a bend in a salt marsh slough where there is plenty of natural cover nearby for concealment and his decoys will be visible to passing birds. He stakes his canoe to the bottom with poles and hangs camo netting between the poles to serve as a blind. He always attaches one decoy to a jerk string. Sometimes he uses a tent stake rigged with a bungee cord, which allows him to make a big splash, but he mainly uses a 50-foot length of sinking crab-pot cord.

Using his own wooden decoys is one of the most important aspects of the hunt for Talton. “When you hunt ducks, you spend a little time looking at real ducks and a lot of time looking at your decoys,” he says. “So I use decoys that I like to look at.”

According to Brook Richard of Higdon Decoys, intense hunting pressure has forced waterfowlers to get creative when hunting white-fronted geese in east-central Arkansas. “Ten or 15 years ago, specklebellies were easy to hunt,” he says, “but as the interest in hunting these birds has increased, the same old tactics are not nearly as effective as they used to be.”

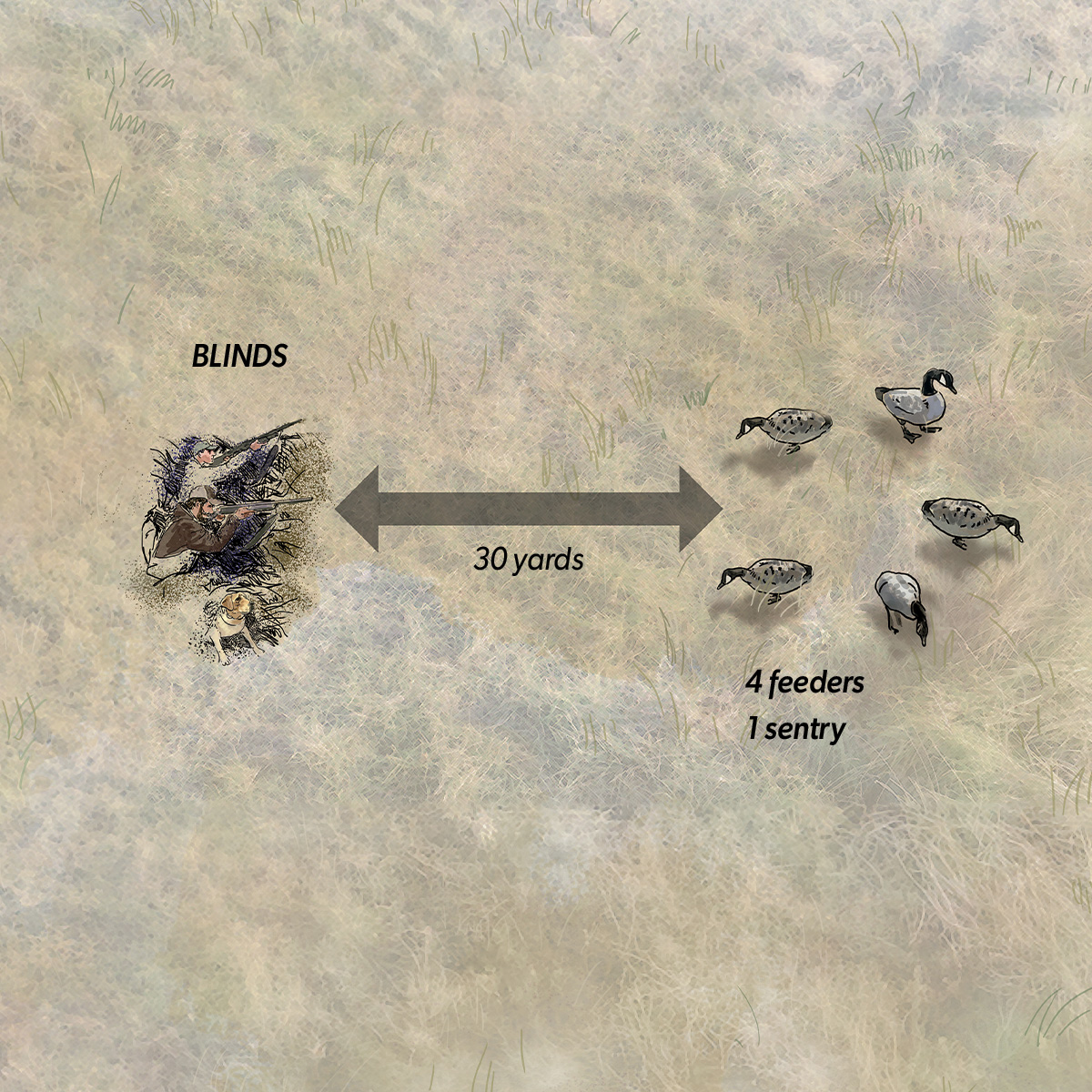

Instead of setting a large spread like many other hunters do, Richard has simplified his rig to only five full-body decoys. “That’s my standard spread,” he says. “I can carry five decoys and a layout blind anywhere I need to go.”

Richard packs his gear into the middle of rice fields, away from levees and ditches that geese have learned to associate with danger. Ideally, he likes to set up between or adjacent to large concentrations of feeding geese, so he can pick off birds trading back and forth. “They all go to the same place first thing in the morning; then at about 9 or 10 o’clock they will start to fly around in small bunches. I am using my decoy spread to paint a picture of a few geese that have landed apart from the others, or maybe they look like the first birds to find tomorrow’s feed,” he says.

Brook Richard’s downsized specklebelly spread simulates a small flock that has just landed and started feeding.

Richard’s downsized speck spread consists of one decoy with an upright head position and four feeders, or just five feeders, which he places facing in different directions. The spread simulates a small flock of geese that has just landed and started to feed. Richard sets the decoys in roughly a five-yard circle, spread out just enough that they don’t block the view of the others to incoming flocks.

He places his decoys no farther away from his position than he wants to shoot—about 35 yards—and sets up with the sun at his back. He uses a MOmarsh Invisilay layout blind, which comes with metal “feet” that help keep hunters out of the mud and water. “In the old days we wore ghillie jackets and waders and tried not to get too wet,” he says, “but this is much more comfortable.”

If Richard can see or hear specklebellies in the distance, he calls them. As the birds get closer, he’ll maintain the volume but reduce the frequency of the calls, so he’ll have something in reserve if they start to slide off to one side. Late-season specks will often circle two or three times to get a good look at the decoys before swinging around to come in.

“When you downsize your decoy spread, everything else has to be better,” Richard says. “Your hide, your decoys, and your calling all have to be just right. When you get out in the middle of a rice field, it’s an intimate hunt. I love the challenge of it.”

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy