The Lovelock Spread

A century ago, archaeologists working in the Nevada desert discovered the world’s oldest-known duck decoys, providing today’s hunters with a fascinating glimpse into waterfowling’s ancient origins

A century ago, archaeologists working in the Nevada desert discovered the world’s oldest-known duck decoys, providing today’s hunters with a fascinating glimpse into waterfowling’s ancient origins

By Chris Madson

It was his last hunt of the fall, I’d guess. He hunted the cold front in the morning with the faith all waterfowlers have in such things; then, as the temperature fell, he gathered his spread and stored it for the winter, figuring on coming back when the birds returned. The flocks returned the following spring, as they always have and, God willing, always will. The hunter never did.

It fell to a couple of curious young men to retrieve the decoys. Mark Harrington, a veteran ethnologist with the Museum of the American Indian in New York City, heard a tantalizing report of excavations in the desert of northwestern Nevada. In the process of digging bat guano, which was to be used for fertilizer, in a shallow cave near the settlement of Lovelock, some miners had come across an unusually rich cache of native artifacts along with some burials. Reports of the find had made their way to the University of California Berkeley, and officials there sent Llewellyn Loud, a self-taught archaeologist with the university, to investigate.

The path to Nevada’s Lovelock Cave (top), where researchers discovered more than 10,000 native artifacts, including 11 remarkably well preserved duck decoys (above) that were later estimated to be more than 2,000 years old.

Loud spent the summer of 1912 digging exploratory pits in the cave. After four months’ work, he had found an astounding 10,000 specimens, including exquisite pieces of basketry, woven mats, nets, and woven sandals. These artifacts piqued the interest of many specialists. Unfortunately, a lack of funding prevented a return to Lovelock Cave the next summer, and the cataclysm of World War I and its aftermath diverted the world’s attention to more pressing matters over the subsequent decade. It was 1924 when Harrington convinced his superiors to fund a return to Lovelock. Loud, still at Berkeley, was happy to lend his experience to the project.

As they were excavating near the mouth of the cave, they came upon one of 40 storage pits they eventually discovered. Like most of the pits, this one was lined with mats woven from rushes, and it contained two woven baskets, apparently intended as containers for seeds. Under it all were several large rocks.

The Lovelock decoys were found buried under some woven baskets and large rocks, where their owner had apparently hidden them away until his next hunt.

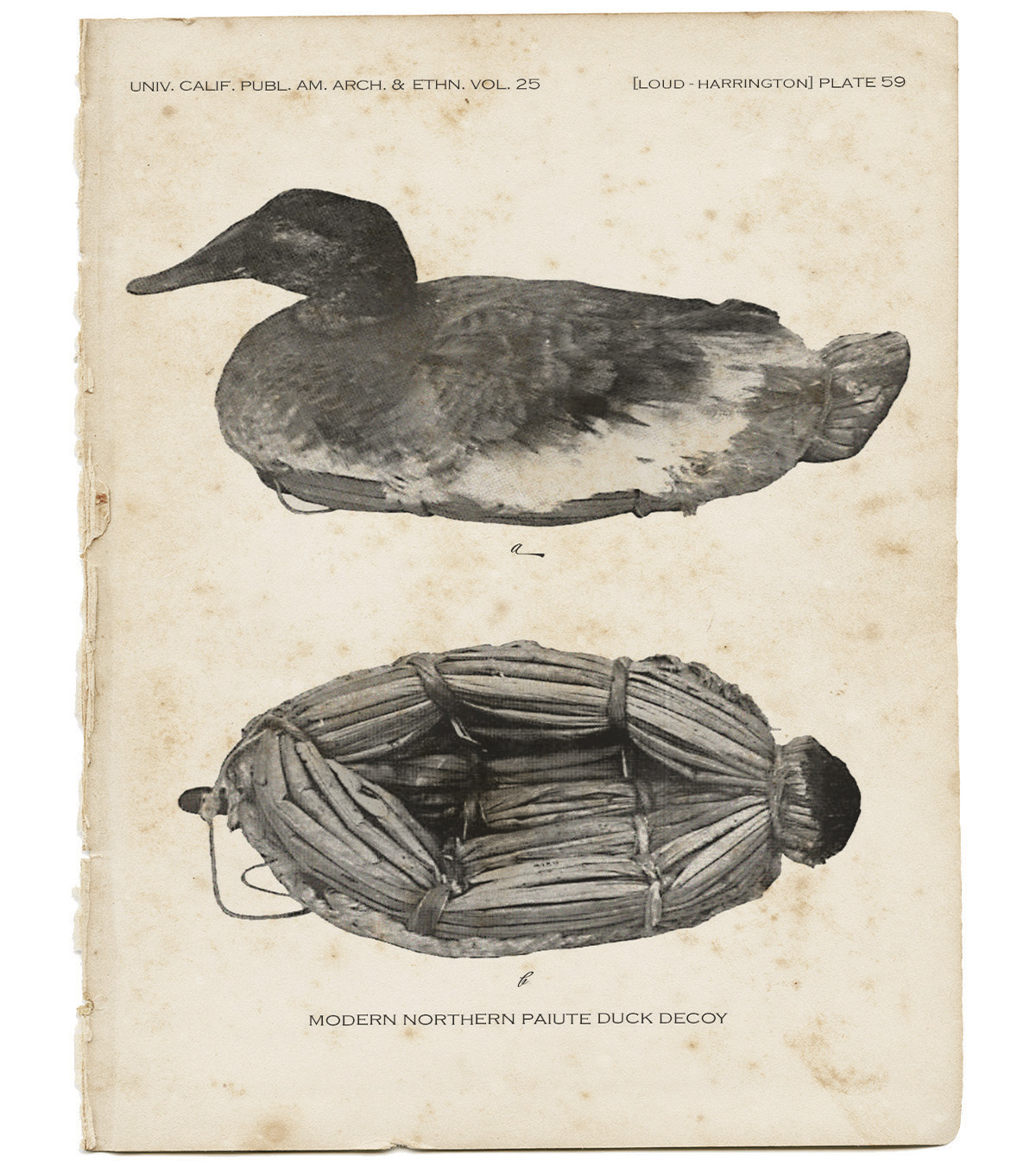

When they moved the rocks, they found another bundle, “a bulky package wrapped in rush matting,” Harrington later wrote. “This contained 11 remarkable decoys made of rushes, most of them feathered and painted to represent ducks; a rush bag full of feathers; feathers wrapped in a piece of mat; a bunch of feathers tied with string; and two bundles of snares made of string and twigs, all in excellent condition. Some waterfowl hunter had hid his decoys here against another season. He may have filled the pit with refuse as an added precaution, but if not, anyone who looked into it saw only the stones and lining of an apparently empty storage cache.”

Excellent condition, indeed. Anyone who knows waterfowl can look at these decoys and recognize them immediately, not just as ducks, but as canvasbacks, as exquisite in their own way as the decorative decoys we admire from today’s generation of carvers.

For waterfowlers, these decoys are immediately recognizable as canvasbacks. Even today, it’s difficult to not admire the craftsmanship and artistry of their maker.

Judging from the admittedly disturbed stratigraphy, Harrington estimated that the decoys were about 1,200 years old. In the early 1980s, a new generation of specialists applied carbon-14 dating techniques and found they were far older— analysis of material from two of the decoys yielded dates of 2,080 and 2,250 years before present, making them the world’s oldest-known waterfowl decoys. The master who made them was hunting over a spread of canvasback blocks before the birth of Christ.

How had that last hunt gone for him? I wonder. The desert of western Nevada still has a few wetlands. The Lovelock waterfowler probably hunted the marshes on the margin of the Humboldt Sink, part of the ancient Lake Lahontan fed by the Humboldt River, or wetlands in the Carson Sink just to the south and east. The geology and archaeology of those far-off days are jumbled. There may have been a drought at about the time of his last hunt, but since there were no irrigation diversions, it’s likely that the shallow lakes in the basins were generally larger than they are today, with extensive wetland margins—perfect habitat for a waterfowl population that was probably near an all-time peak. Little wonder that duck hunting was ingrained into the local culture.

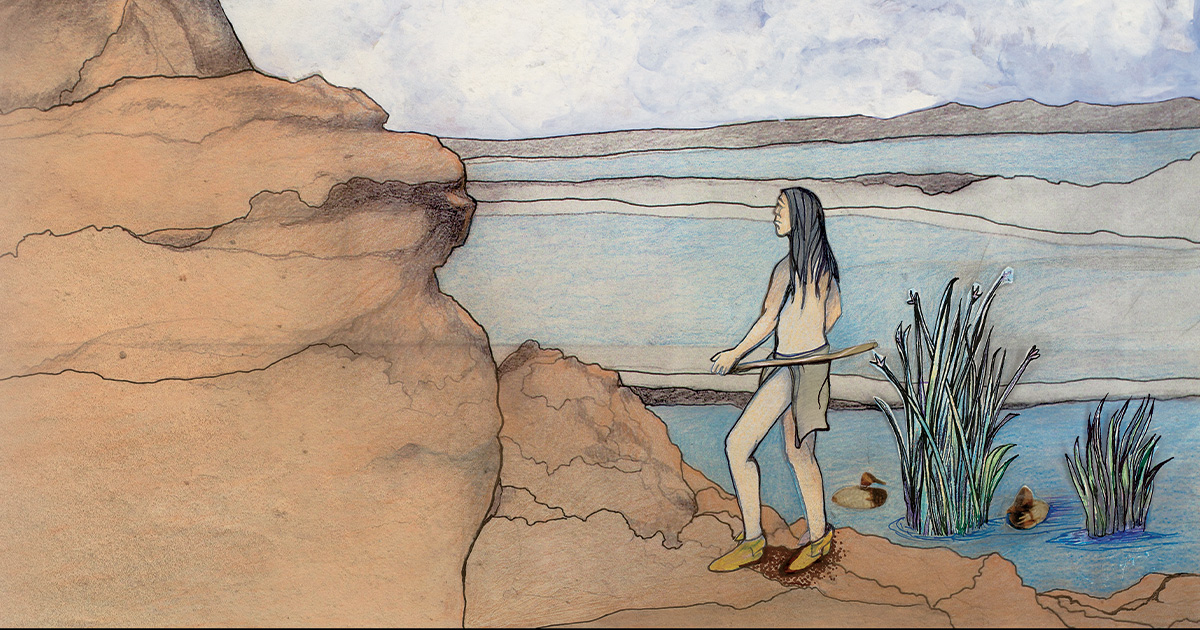

While the subsistence hunters of that time were undoubtedly more inured to cold than we are today, I doubt this hunter was inclined to stand hip-deep in the marsh for hours on end, especially after the first cold fronts had triggered the migration. While he and his cohorts left no evidence of watercraft, the first white explorers in the region saw the resident Paiutes using boats made from bundles of bulrush held together with cattails.

In the 1940s, a Paiute elder demonstrated the technique for Margaret Wheat, a young geologist who had taken an interest in Paiute history and culture. “Not use a paddle,” he explained as he launched his one-man craft. “Just use stick to push.” He told Wheat that “tule boats never sank even after they had absorbed much water.”

The rudiments of making decoys out of the same materials came down through the millennia to the Paiutes. The elder showed Wheat how he made a floating body of bulrush and cattail to stuff into the skin of a pintail he’d killed. He stuffed the neck with cattail and held it vertical with a greasewood stick run inside the skin and through the top of the skull, then anchored the other end in the bulrush body.

Excavations in Lovelock Cave and several other rock shelters nearby had found decoys built in much the same way, along with heads and necks that had been stuffed and may well have been used in clumps of vegetation the hunters gathered after they’d chosen a place to set up.

Some native hunters fashioned realistic decoys by stretching a duck skin over a form made from rushes. The decoys were anchored with a stone or a stick

driven into the mud.

A duck skin offered the ultimate in realism and relieved the person making the decoy of the need to fine-tune the bulrush body and head to imitate the genuine article. That raises the question of why at least one ancient hunter preferred to make his decoys without skins, carefully crafting realistic bodies and heads instead, then painting them or using a few feathers on the bodies. Duck skins couldn’t have been hard to get. Did the unfeathered tule decoys last longer than the stuffed skins? Did they ride better in the water? The answer died with the maker.

At least one modern Paiute hunter anchored several decoys by strings attached to a willow stick driven into the mud. While on a scientific survey in the area in 1867, ornithologist Robert Ridgway reported that the Paiutes he watched anchored their decoys “by a stone tied to a string, the other end of which is fastened to the bill,” an arrangement that could give the decoy a feeding action in a stiff wind.

The entrance to Lovelock Cave.

Ridgway made this comment under his description of a redhead, implying that most of the decoys he saw were of this species. Most of the decoys that have been collected from Native Americans use canvasback skins, and it’s worth noting that the oldest Lovelock decoys also imitate cans. That may be more than coincidence.

Diving ducks aren’t as quick off the water as dabblers, which may have left them a little more vulnerable to neolithic weapons. The artifacts from Lovelock include the remnants of bows as well as spear throwers and four “throwing clubs.” Any of these implements could kill or cripple waterfowl at close range. One modern Paiute tells of special “duck arrows” with main shafts of cane and heavier foreshafts of greasewood and nothing more than a sharpened wooden point, apparently designed to lodge in the bird and impede its flight or, if it hit the water, its escape. An atlatl dart would do much the same thing. A throwing stick launched into a dense flock could, at least in theory, break necks or wings.

Ancient traditions continue in this more modern example of a Paiute duck decoy, circa 1920.

One or two hunters could use any of these weapons to take a bird or two out of any flock that decoyed close enough, and it’s possible that the snares found in the cache were also pressed into use.

And the apparent preference for decoys that imitated diving ducks suggests another possibility: Could a group of hunters decoy a flock of divers and drive them into a strategically placed net? The remains of beautifully crafted nets have been found in Lovelock Cave and several other archaeological sites in the area, and driving jackrabbits into long, intricately woven nets was found to be a regular foraging technique among Paiutes centuries later, when they first encountered white explorers.

The beauty of ducks in flight inspires the hopes of waterfowl hunters across the centuries.

Speaking with anthropologist Catherine Fowler, a Paiute elder described setting a long net in a channel, staked with willow poles leaning at a 45-degree angle. A flock of diving ducks would land in the channel, only to be flushed into the waiting net, where their weight would dislodge the willow poles and allow the net to collapse over them. This technique also worked when waterfowl were flightless in late summer. It was said this worked best in the evening or at night when the net was hard to see. The more drivers available to move the ducks, the more likely this technique was to yield a major haul of birds, although a couple of hunters might make it work if the birds were mainly canvasbacks or redheads.

The idea of netting flocks of waterfowl may grate a little on modern sensibilities. Clearly, the Lovelock hunters were taking ducks, geese, swans, and other quarry not for sport, but to survive. If the traditions of the northern Paiute are any guide, these pre-Columbian people took as much game as the season and their technology allowed, feasting when it was fresh and drying as much as they could for the lean months when the birds went south, the fish were safe under the ice, and the wild crops in the surrounding landscape were dormant. Even at its most benevolent, the Nevada desert has always been hard country that often leaves little margin for survival—sometimes, none at all.

The craftsman who stored those decoys led a hard life—it doesn’t take much imagination to understand why he never came back for them. I hope his end was merciful. The Lovelock decoys are a monument to his skill. They reach across an unimaginable span of time, across staggering differences in technology, culture, language, and lineage as a reminder of what we, in these complicated times, still hold in common with him. I’d like to think that, when he lay down to rest after that last hunt so long ago, his dreams were filled with the sound of wind in the tules and the rush of wings.

As mine so often are.

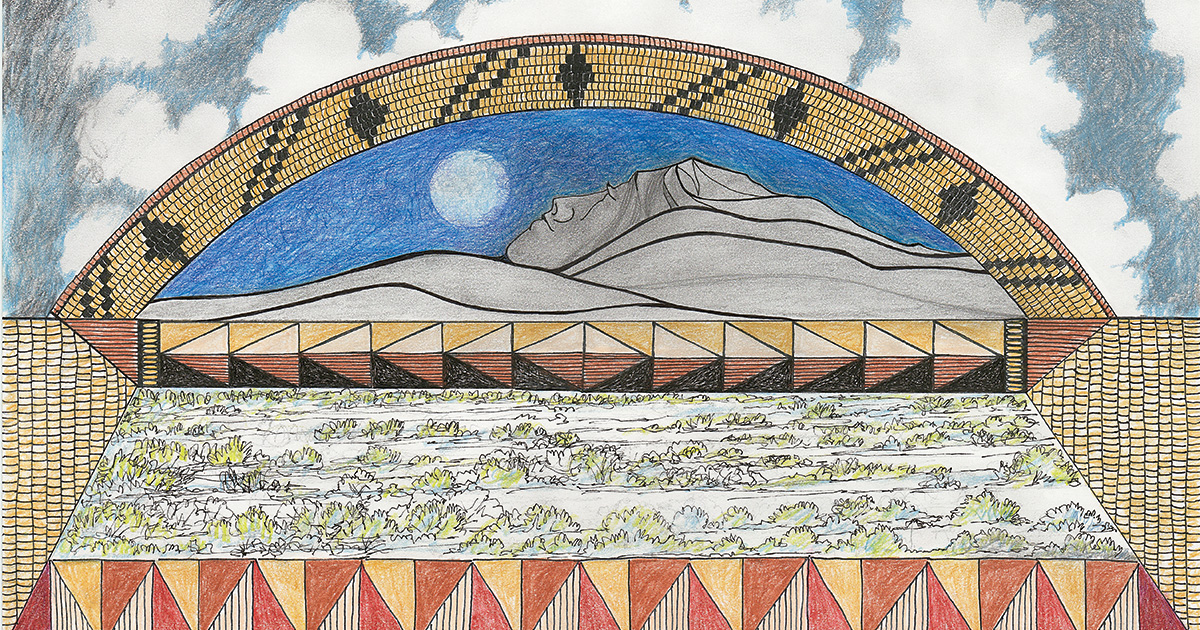

Ben Aleck lives near Pyramid Lake, Nevada, and is a member of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe (Kooyooe Tukadu). Aleck received his formal education at the California College of Art (formerly the California College of Arts and Crafts) and graduated in 1972 with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree.

Aleck’s early work consisted mainly of oil paintings with the human figure as subject matter. More recent pieces feature drawings using pen and ink and graphite on paper. His current work is mixed media, using water-based paint, ink, dyes, and natural materials. The human figure is still a major theme; however, he incorporates a variety of materials and subjects. Some of his works include statements relating to cultural issues and environmental concerns.

The Beauty of the Great Basin, 2019. Pen, ink, colored pencil, and graphite on paper, 11”x17”. This piece was created for a mural inside the Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum.

Aleck has participated in several group shows in Nevada and other Western states. His works have been shown at the Oakland Museum of California; the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC; the Stewart Indian School Cultural Center and Museum in Carson City, Nevada; and the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno.

For more information about Aleck and other native artists from the region, visit greatbasinnativeartists.com.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy