Building a Better Duck Load

A look back at the evolution of waterfowling ammo, from the black powder era to today’s state-of-the-art shotshells

A look back at the evolution of waterfowling ammo, from the black powder era to today’s state-of-the-art shotshells

It’s easy to forget that the duck load that you casually drop in the loading port of your autoloader is the result of 150 years of ammo evolution. The invention of cartridge ammunition played a huge part in turning waterfowling into the sport we know today. Before cartridges, every shot was a hand load. Hit or miss, you had to stand up to ram pellets, powder, and wadding down the barrel, and then you had to prime the gun before it was ready to shoot again.

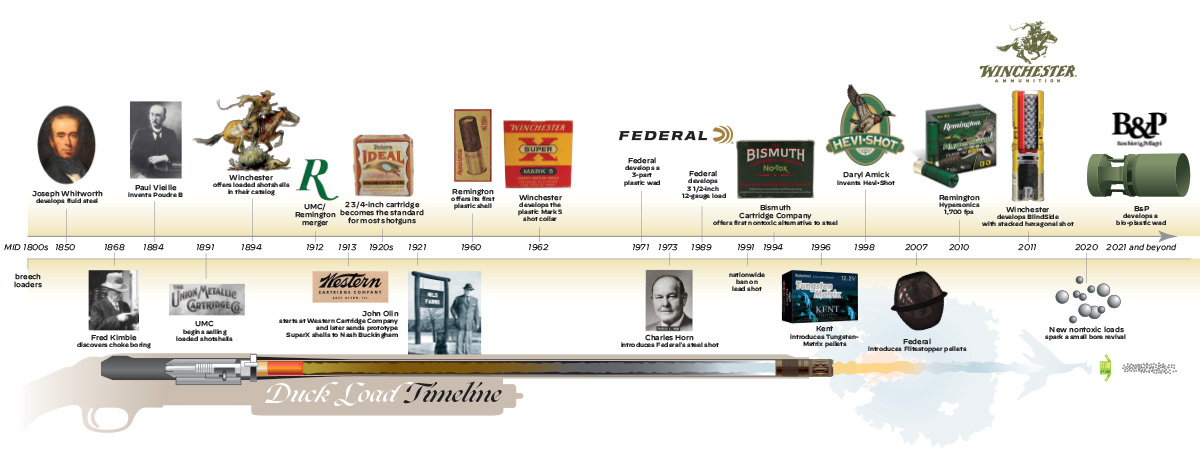

Starting with the development of breechloaders in the 19th century and continuing through to the 1980s, lead loads for waterfowling became more efficient, more weatherproof, and more reliable. While shotshells have always evolved, there have been flurries of development throughout history. The first centered around smokeless powders in the latter part of the 19th century. The 1920s and '30s saw improvements in shot and refinement of powders. Widespread use of plastics improved shotshell performance in the 1960s and '70s. The present era began in 1991, with the nationwide switch to nontoxic pellets, and the waterfowl ammo market has been marked by constant developments, changes, and trends ever since. There will be more change in the future, and as we wonder what may come next, it’s worth taking a look back to see how far waterfowl loads have come.

The latter half of the 19th century saw the birth of modern shotguns and ammunition. Gun makers experimented with breechloaders for centuries before practical models appeared in the mid-1800s. Also in the midcentury, Joseph Whitworth’s development of fluid steel enabled gunsmiths to make lighter, stronger gun barrels that could withstand higher pressures. In 1868, trapshooter and duck hunter Fred Kimble of Illinois discovered choke boring while opening the bore diameter of an old musket barrel. Pinfire break-action shotguns were popular during this period, but they used black powder cartridges with a built-in firing pin that could detonate when dropped.

Modern guns needed modern ammunition. Primers replaced percussion caps and pinfires in the 1860s. Two effective primer designs were invented almost simultaneously by American Hiram Berdan and Colonel Edward Boxer of England. In 1864, Prussian artillery Captain Johann Edward Schultze invented a type of nitrocellulose-based gunpowder made by soaking cellulose or cotton in nitric and sulfuric acids. After Schultze’s factory burned down in 1868, Englishmen Clement Dale and William Bailey saw the powder’s potential and bought Schultze’s brand name and process. Establishing a factory in a safely remote area of Hampshire village, they built Schultze powder into a worldwide concern. Meanwhile, French chemist Paul Vieille invented Poudre B (the B stood for “blanche,” or “white,” to distinguish it from black powder) in 1884. Both Schultze and Poudre B were smokeless powders that could achieve higher velocities and pressures than black powder could. Unlike black powder, these propellants didn’t produce billowing clouds of sulfurous smoke, nor did they badly foul gun barrels with residue that attracted moisture and caused guns to rust.

Primable brass cartridges came next, followed by paper hulls with brass bases, which appeared around 1875. Fully loaded factory shells appeared just before the century’s end. Union Metallic Cartridge Company, which would merge with Remington in 1912, offered loaded shotshells in their 1891 catalog. Winchester listed them in their 1894 catalog.

Despite the advantages of smokeless powder, ammo makers loaded black powder cartridges well into the 20th century, as there were plenty of old guns still in use. While the 1916 Winchester catalog still listed 2-ounce black powder shells for 8-gauge guns, black powder was on its way out. The following decades would see major advances in shotshell design.

Shotshell lengths were standardized at 2 3/4 inches for all shotguns in the 1920s, with the exception of the 10-gauge, which used a 2 7/8-inch hull, and the .410, which had a 2 1/2-inch cartridge. Noncorrosive primers, made with lead styphnate in place of fulminate of mercury, reduced wear on gun barrels and chambers during the same period.

The higher velocities and pressures generated by smokeless powders presented ballistic challenges that became the focus of shotshell design in the 1920s and '30s. Lead shot, unprotected in the shell, was deformed both by setback forces when the shell was fired and by contact with the bore. Shot that was squished out of round patterned poorly, and the patterns themselves strung out as deformed pellets lagged behind the rest. In England, Major Gerald Burrard tried to measure shot-string lengths by firing at an armored Model T as it drove past him at various speeds and distances.

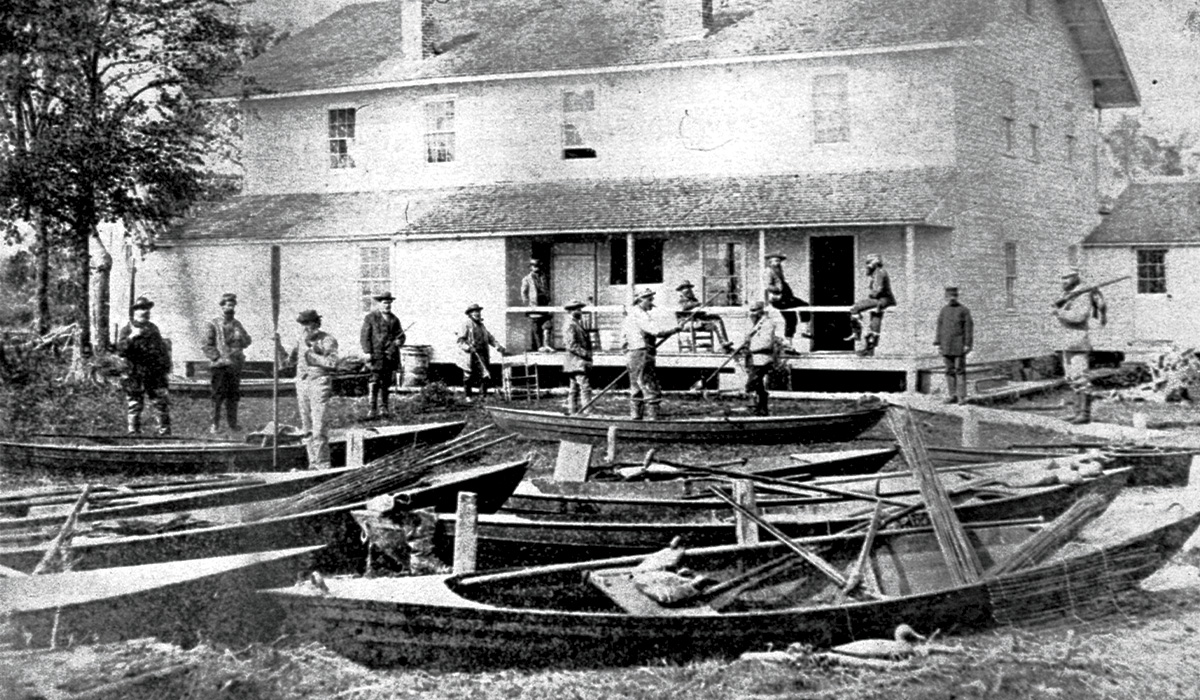

Waterfowlers gather at Winous Point Shooting Club in Ohio, one of the nation’s oldest duck clubs.

Around the same time, in the United States, a brilliant young chemical engineer, waterfowler, and retriever breeder named John Olin invented and patented a “flightometer” to measure shot strings, and he went to work on the problem. Olin started work at his father’s Western Cartridge Company in 1913, and before he was done had built the company into Winchester Ammunition, which was one part of Olin Industries. Olin also worked to improve waterfowl loads through the use of progressive powders, which treated shot more gently upon ignition, and harder lead shot. In the fall of 1921, Olin sent eight boxes of new shells along with a specially bored Fox shotgun to his friend Nash Buckingham, who reported that the new ammo extended the effective range of his shooting by 15 to 20 yards. The shells were prototypes of what would become Winchester Super X shotshells, and Buckingham was so impressed with the Fox that he ordered a customized version from gunsmith Burt Becker. Colonel Harold P. Sheldon gave Buckingham’s famous Fox the nickname Bo Whoop after the gun’s distinctive hollow report.

Olin kept improving Super X ammo, adding copper plating to the pellets and creating 3-inch 12-gauge and 3 1/2-inch 10-gauge magnum loads for waterfowlers. He also created a 3-inch .410 load to go along with the Model 42 pump for upland bird hunters. Winchester didn’t introduce 3-inch 20-gauge loads until 1954.

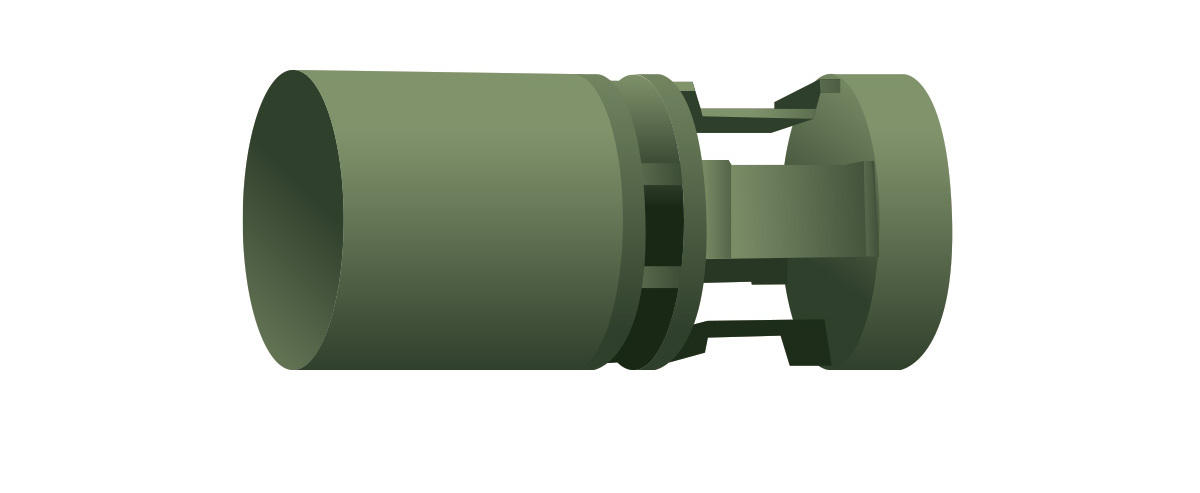

Everything turned to plastic in the 1960s, including shotshells. Remington’s plastic SP hull appeared in 1960. Plastic hulls had major advantages over paper. They were impervious to moisture and swelling, and they could be reloaded many times. In 1962, Winchester used a plastic wrap, the Mark 5 shot collar, to protect pellets from bore deformation, improving patterns dramatically. All-plastic wads followed soon after. Remington’s Power Piston wads not only had plastic petals to protect shot, but the bottom section was designed to collapse under recoil, softening the jolt to the lead payload and the shooter alike.

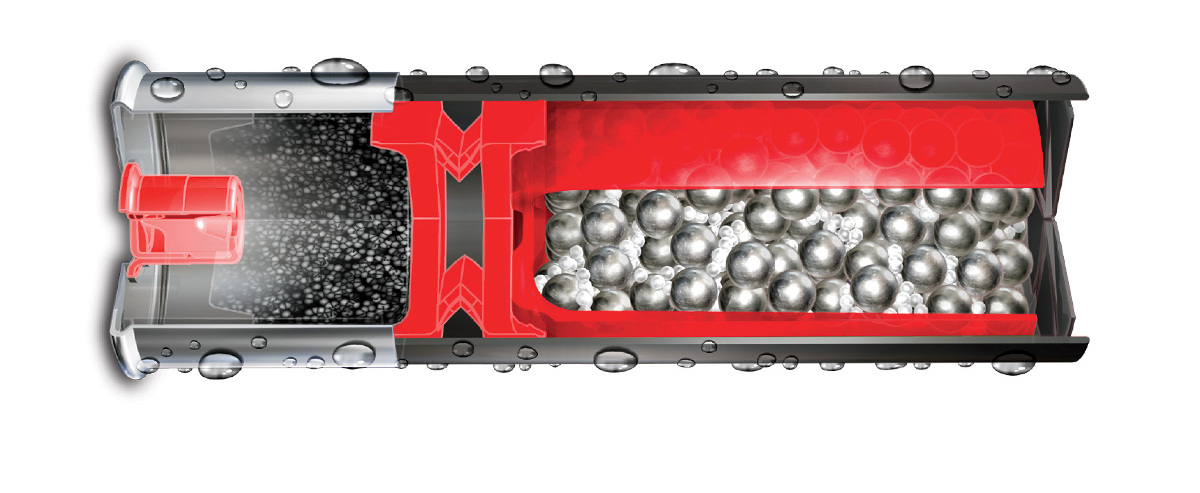

While the first Mark 5 shells had fiber base wads and plastic collars, it wasn’t long before shotshells went entirely plastic. A 1971 Federal ad shows a cutaway of a duck load with a three-part plastic wad incorporating the shot cup, the collapsing pillar, and the over-powder wad all as one piece. Finally, ground plastic buffering material known as “grex” was loaded in Winchester’s Double X and Federal’s Premium magnums in the 1970s. The plastic particles surrounded and cushioned shot to keep pellets from pressing against each other and deforming in the bore.

By the late 1970s, Winchester Double X, Federal Premium, and Remington Premier ammo, all loaded with hard, copper-plated, buffered shot and protected by plastic shot cups, were some of the best-patterning, hardest-hitting waterfowl loads ever made. In the mid-'70s, Field & Stream Shooting Editor Bob Brister conducted a series of patterning tests in which he shot at 16-foot-long sheets of paper mounted on a boat trailer being towed behind a station wagon driven by his wife. Brister's tests showed that state-of-the-art, high-quality buffered shotshells not only patterned better than the ordinary “duck and pheasant” loads of the time, but the moving targets proved that they produced much shorter shot strings.

Even as copper-plated shot and plastic buffer materials improved the performance of lead ammo, Federal Cartridge Company’s longtime president Charles Horn, who was also an ardent conservationist, saw the future. Biologists had known for years that waterfowl died from lead poisoning as they ingested pellets incidentally while feeding on the bottom of wetlands. One of his last acts at Federal was to oversee introduction of steel shotshells in 1973.

With a ban on lead shot looming throughout the 1980s, ammo makers worked to improve the only existing alternative: steel shot. The industry encouraged hunters to choose more open chokes and to go up two or three pellet sizes to compensate for steel’s low density and tight patterning characteristics. The need for larger hulls to hold magnum loads of larger steel pellets helped the 10-gauge make a brief comeback. The 10 was soon joined, and then eclipsed, by Federal’s new 3 1/2-inch 12-gauge cartridge. The new shell debuted in 1989 along with Mossberg's 835 Ulti-Mag pump chambered for 3 1/2-inch loads. Benelli’s 3 1/2-inch Super Black Eagle semiauto came out in 1992, and the 3 1/2-inch cartridge went mainstream.

Steel loads improved throughout the ’90s. New primers and powders increased steel velocities and reduced fouling in the barrel. Lacquer around the primer and crimp prevented pellet rust. New wads guarded against barrel damage while allowing larger payloads of steel pellets.

Estate Cartridge was the first ammo maker to offer what at the time were the first modern high-velocity loads rated at 1,450 fps. Additional speed and improved components made steel much more effective. Remington and Federal each offered the first Duplex ammo loaded with different-sized pellets. Federal even briefly offered a Tri-Power shell with three sizes of shot. While Duplex loads didn’t catch on at the time, the idea would stage a comeback years later.

Despite the improvements, steel was still steel—relatively ballistically inefficient and hard on soft steel barrels. Ammo makers and entrepreneurs looked for alternatives. Ontario carpenter John Brown, who enjoyed hunting with vintage shotguns, partnered with wealthy gun collector and publisher Robert Petersen to develop bismuth-tin alloy pellets, which had a density between lead and steel and were safe to use in older guns. Loads produced by the Bismuth Cartridge Company hit the market in time for the 1994 waterfowl season.

Tungsten, a hard, dense, expensive metal, emerged as another nontoxic alternative. In 1996, Kent Cartridge introduced Tungsten-Matrix pellets, consisting of powdered tungsten blended with a soft polymer. These pellets were almost as dense as lead and just as forgiving in gun barrels. In the next two years, Federal introduced a pair of tungsten-based pellets. One was a tungsten-polymer blend similar to the Kent product while the other was a very hard tungsten-iron pellet that required an extra-thick wad with overlapping petals to prevent barrel damage.

The past quarter-century has seen ammunition development branch off in many directions, driven by attempts to improve steel and by the need to deal with rising prices of pellet materials. The beginning of the 21st century brought pellets that outperformed lead. Daryl Amick, the metallurgist who had worked on Federal’s two tungsten projects, had retired and was living in Oregon when a hunting partner offered to back him financially in the development of a better type of nontoxic shot. The resulting Hevi-Shot pellets were denser than lead and outperformed even the best buffered magnums of the lead-shot era. Soon, several blends of denser-than-lead tungsten-iron ammo joined Hevi-Shot: Winchester Xtended Range, Remington Wingmaster HD, and Federal Heavyweight. High material prices killed off Heavyweight and Xtended Range and forced Hevi-Shot to reduce the density of its pellets. Bismuth disappeared from the market at times, too, as the material grew scarce and prices rose.

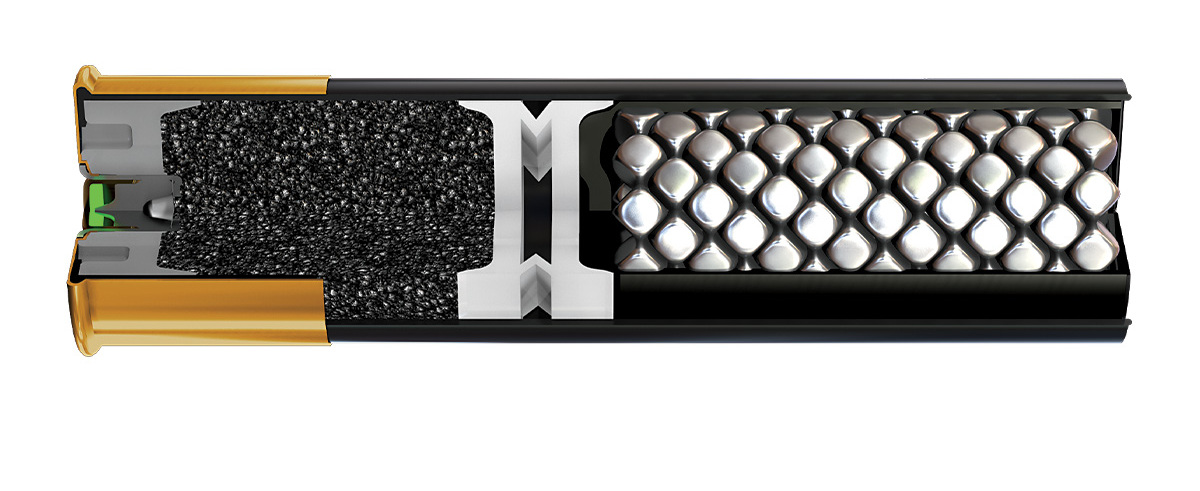

Meanwhile the industry responded in ingenious ways to try to improve steel. Federal’s Black Cloud introduced the idea of new pellet shapes in 2007 with ridged Flitestoppers, which were designed to increase wound trauma. It also used a unique rear-braking wad that tightened patterns. Introduced in 2011, Remington Hypersonic loads pushed pellets to new velocities. The two-stage shells featured a small charge of powder in a hollow stem over the primer that ignited first, pushing the wad far enough that the main charge could ignite without dangerous pressure spikes. The shells hit the previously unheard-of velocity of 1,700 fps. Winchester would follow in 2015 with hex-shaped Blind Side shot. Duplex shells reappeared in 2014. Hevi-Shot’s Hevi-Metal loads mixed Hevi-Shot and steel pellets to punch up performance while keeping the price down.

The global price of raw bismuth fell sharply in the mid-2010s, and raw tungsten prices dipped too. Ammo makers took advantage of the opportunity to load bismuth shells again and to take another look at improving the pellets. New alloy formulations made second-generation bismuth less brittle. Both Winchester and Boss Shotshells introduced buffered bismuth shells that patterned better than the competition. Lower tungsten prices and new ownership by Vista Outdoor brought the original Hevi-Shot back at a price many hunters were willing to pay. Tungsten Super Shot (TSS), the densest pellets of all, went from a handloader's secret to production ammo from Apex Ammunition and Federal in the late 2010s. The sky-high price of TSS relegated it mostly to stacked loads and turkey ammo.

The proliferation of bismuth and the return of original Hevi-Shot has sparked a resurgence of small-bore shotguns among waterfowlers in recent years. Browning's introduction of the Sweet 16 A5 almost single-handedly started a 16-gauge revival in 2016. Many hunters went even smaller, downsizing to 20-gauges and even 28s, especially after the introduction of a new 3-inch magnum 28-gauge by Benelli and Fiocchi.

As of this writing, bismuth prices have soared, and raw tungsten costs significantly more as well. The small-bore boom may be over just as it's starting. However, there are already rumors of new pellet materials becoming available in the near future, which could once again change the ammo landscape. In the meantime, after 50 years of development, the state of steel ammo is better than ever. It too may have to evolve.

The push to replace single-use plastics has already started across the Atlantic. European manufacturers are leading the way with bio-polymer wads like B&P's Green Core bio-plastic wad. In the United States, Federal now offers both steel and lead loads in target sizes with paper wads. While components include a new base wad that provides improved gas seals, the paper shot cups aren't yet thick enough to protect barrels from larger shot sizes. Perhaps in the future some other discovery will lead to new, currently unimagined biodegradable components. All we can be sure of is that shotshells have evolved continually since their invention, and they will keep evolving and improving in the years ahead.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy