Cotton and the King

A sickly puppy that had cheated death. A poor farm kid with a unique gift. When fate brought them together, they made history

A sickly puppy that had cheated death. A poor farm kid with a unique gift. When fate brought them together, they made history

By Chris Madson

They were born on the same day, 34 years apart. Which considering the way things turned out, seems like something more than a simple coincidence.

The black Labrador retriever was whelped on April 3, 1948, in Storm Lake, Iowa, on a blustery night with the first scent of spring on the wind. His sire came from Arden kennels, owned by New York Governor William Averell Harriman. His mother traced her lineage back to the Banchory kennels of Countess Lorna Howe in England.

There were eight pups in the litter, five males and three females. By early fall, all eight had been sold. Two of the males went to new homes in Omaha, Nebraska, one to E.J. Karnes and the other to Robert Howard. The price for each pup was $50. Ed Quinn, the breeder, thought that Karnes got the better of the two, "a better retriever as a puppy, and superior to Howard's pup in every way," Quinn said.

A crowd watches the 1952 National Championship Stake in Weldon Spring, Missouri, where King Buck won his first national title.

Photo SHOWMANSHOOTER.COM

Unfortunately, Karnes never had a chance to find out how that promise might have been fulfilled. Within days after their arrival in Omaha, both youngsters came down with distemper. Karnes took his puppy to a vet, where it soon died.

Howard made a nest of blankets in a basket next to the furnace in his basement, and for almost a month, he and his wife fought to save the little dog that was so weak he couldn't stand. Mrs. Howard tempted him with an occasional egg, kept him warm, and they both waited.

"One night I went downstairs to have a look at him," Howard remembered later, "and he managed to stand in his basket and greet me. I knew then that he was going to make it."

Recovery was slow. The young dog was thin and lacked appetite. Occasionally, he passed a bloody stool, suggesting that he might have suffered permanent internal damage. A vet told Howard that the dog had a bad heart and shouldn't be used as a hunter.

But, as the dog recovered, he showed unusual intelligence and the kind of hustle trainers look for in a retriever. The youngster needed a name, and Howard settled on "Buck," because it didn't rhyme with any commands and was easy to yell. In a moment of completely unwarranted optimism, he added the word "King," in the hope that the dog would overcome his inauspicious beginning and make a mark in the rapidly growing world of Labrador field trials

King Buck was born with exceptional intelligence and drive. Pershall harnessed and refined those talents to create a champion.

Photo Winchester-Nilo

"A real brainy dog," Howard recalled. "Buck was also eager and affectionate with me." And his talent was unmistakable. He won a licensed derby when he was only 18 months old. Soon after that first victory, he took first place in the Missouri Valley Hunt Club's licensed field trial in western Iowa.

Howard was beginning to appreciate Buck's potential. This was a dog that should be run in the biggest trials on the continent, Howard saw, but he couldn't afford that kind of effort. So he approached Byron Grunwald of Omaha with an offer to sell King Buck to Grunwald for $500 if Howard could continue to train the dog and handle him in trials. The deal went through in December 1949. Before Buck reached his second birthday, he had taken a first, two seconds, and several third places in trials across the Midwest.

King Buck had his off days. He sometimes struggled to mark falling birds, which meant he occasionally had to depend on his nose, quartering until he found what he was after. Following one trial, a judge approached Howard. "Bob," he said, "that dog is nothing but a runner and will never amount to a damn. If you're smart, you'll get rid of him."

Photo Winchester-Nilo

Two weeks later, Buck won the open trial at Eagle Lake, Wisconsin. Howard said, "I never claimed that Buck was the world's greatest marker, but, Lordy, the way that dog entered the water and the way he took a line!"

In the two weeks after Eagle Lake, Buck took second place in two more trials, finishing the requirements for official designation as "field champion."

It was about that time that John M. Olin took notice of Buck. Olin, the owner of Winchester-Western, had constructed a new kennel in Brighton, Illinois, and was looking for dogs to build its reputation. He approached Grunwald, who had already turned down $5,000 for the young prospect. Olin upped the ante, and King Buck was headed for Nilo Kennels.

John M. Olin, the owner of Winchester-Western, purchased King Buck and brought him to Nilo Farms, his property in Illinois where he established a world-class kennel.

Photo Winchester-Nilo

The man was born on April 3, 1914, to Lewis and Lena Pershall, who were scratching out a living on a hardscrabble farm at the edge of the Ozarks near Walnut Ridge, Arkansas. His mother named him Theodore, but his mop of nearly white blond hair earned him the nickname "Cotton." When Cotton was 13, his family moved to the St. Louis area, where his dad took a job managing a hunting club for Paul Bakewell III, a wealthy insurance executive.

By the time Cotton was 16, he was officially considered a blacksmith in Bakewell's stables, but as his boss's interests turned to field trialing retrievers in the 1930s, Cotton got involved with the dogs. He trained Bakewell's golden retriever, Rip. With Bakewell as his handler in the trials, Rip won the National Open Field Trial Stake in 1939 and received the Field and Stream trophy for outstanding retriever that year and again the following year. Rip's dominance might have continued if he hadn't died of an internal injury suffered in an accident before he was three.

Cotton Pershall was one of the most successful retriever trainers of all time. He trained 28 field champions and won three national titles with multiple dogs. But he said he had never seen another dog like King Buck.

Photo DU/BIRDDOGFOUNDATION.COM

After Rip's passing, Bakewell shifted to Labs, with Cotton still doing the training. In 1942, Bakewell showed up at the national open with another dog Cotton had trainedShed of Arden. Shed won the open stake in 1942, again in 1943, and a third time in 1946. In 1947, Bracken Sweep won the national open, trained and handled by Cotton Pershall. He also trained Marvadel Black Gum, Bakewell's winner in the national open in 1949. With Cotton training and occasionally handling dogs in trials, Bakewell's Deer Creek Kennel won eight of 11 Field and Stream trophies for the high-point retriever of the year between 1939 and 1949.

It's hard to say how long the partnership between Bakewell and Pershall might have lasted if it hadn't been for the tragic loss of Little Pierre of Deer Creek, one of Bakewell's Labs that promised to surpass Shed of Arden as a trial champion. Little Pierre died young under mysterious circumstancesrumor had it that the dog had been poisoned by a jealous competitor. Devastated by the loss and embittered by what he saw as a growing win-at-any-cost attitude in the world of retriever trials, Bakewell steadily withdrew from competition with his dogs. Luckily for Pershall, another wealthy enthusiast had just built a top-flight kennel and bought what he hoped would be a top-flight Lab. All he needed was a top-flight trainer. In 1951, Pershall went to work for John M. Olin.

Photo Winchester-Nilo

Right at the start, the two men had a disagreement. Cotton had his doubts about King Buck. No other pup out of Buck's litter had shown exceptional talent, and Buck's struggles with distemper were cause for concern. Cotton had convinced Olin to buy two other Labs, Hot Coffee of Random Lake and Freehaven Muscles. Of the three, Cotton thought Muscles had the best chance in the big trials. Around the kennel, King Buck was thought of as "J.M.'s dog."

Buck wasn't long in allaying Cotton's doubts. In 1951 he won two field trials, placed second in two, and took third place in two more. His performance earned him an invitation to the National Championship Stake, held that year in Carnation, Washington. He completed 10 of the 11 series in that trial, good enough to show he belonged with the best retrievers in the nation but not good enough to edge out the winner, Ready Always of Marian Hill.

King Buck and (from left) Cotton Pershall, Paul Bakewell, and John Olin with the Field and Stream Challenge Cup, which Buck won in 1952.

Photo SHOWMANSHOOTER.COM

In 1952, Buck took top honors in two trials and placed in three others, earning another invitation to the National Championship Stake, which was held that year in Weldon Spring, Missouri, just outside St. Louis, an easy trip from Nilo Kennels. He finished the tenth series in the trial with a 225-yard water retrieve. Claude Bekins, one of the judges for the event, remarked that, "King Buck gave the best performance throughout the trial that I have ever seen." Bekins scored the three-day performance at 99 out of a possible 100 points. Buck was 1952's champion retrieverthe king in fact, as well as in name.

After the trial, Olin and Buck flew to Stuttgart, Arkansas, one of Olin's favorite hunting spots, for a few days of mallard shooting in the green timber. On the night of their arrival, Olin held a reception for the dog. He filled the sterling silver championship bowl with water and let Buck drink. Then he dumped the water, filled the bowl with champagne, took a drink, and passed it to the man next to him. Each man in turn took a drink out of the bowl to honor the Lab's achievement until one guest refused, unwilling to drink out of the bowl a dog had used. A silence settled over the group as Olin glared at the man, who was invited to leave the premises while he still could.

The next morning, Olin and Buck were in the flooded timber before sunrise. It was a special day, Olin remembered later: "He was one of the finest wild duck retrievers I have ever seen. In spite of his intense field trial training, he loved natural hunting. He used his head in the wild, just as in field trials. That first wild duck shoot was his day, every minute of it, and he made the most of it. He was beautiful to watch."

That night, Buck slept at the foot of Olin's bed, the first time he had ever spent the night outside his kennel.

Photo Winchester-Nilo

Cotton arrived in Stuttgart two days later and was appalled to see the way the dog was being spoiled. "I asked [Mr. Olin] if he had any problems with Buck. Oh, he broke a couple of times, but don't worry about it, Cotton; he'll be all right.' Shoot, it always took me a couple of weeks to get him steadied up again after one of those trips. I'll tell you what, thougha dog that breaks now and then usually has a lot of desire." And desire was what Cotton looked for in a retriever.

In spite of the headaches these expeditions caused for the trainer, the dog and his owner were just fine with the arrangement. For the rest of Buck's life, when he and Olin traveled together, they shared the same bed.

The champion and his trainer spent the spring and summer of 1953 in workouts. In the fall, they emerged to claim three straight field trials before traveling to Easton, Maryland, for Buck's third National Championship Stake. The judges gave him perfect scores in the first nine series, but several dogs closed the gap on the tenth series. The judges called for two additional series to decide the event. Afterwards, one of the judges commented that "in 11 out of 12 series King Buck was faultless in every department on land and in the watermarking, bird sense, manners, steadiness, and control near at hand and far out. It was so apparent to all by the twelfth series that he was the clear and decisive winner that I am sure the official announcement came as an anticlimax."

Still the king.

Buck campaigned for another four years. In 1955, he retired three trophies from the Midwest Field Trial Club in a single day, having won each of them three times. In the nationals, he remained a rock-steady performer. Looking back on his performances, Cotton said, "He always seemed to have some power of knowing when the competition was really rough, and he always came through."

In his last appearance at the nationals, he missed completing the twelfth series. It was the first series he'd missed since the eleventh series in his very first national in 1951. He had completed 63 straight series in seven National Championship Stakes. No other retriever had ever accomplished such a feat.

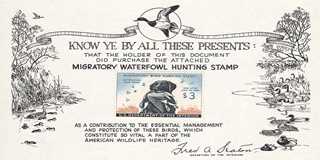

In 1958, the US Fish and Wildlife Service announced the subject for the 1959 federal duck stamp. The authorities had decided that the art on that stamp should include a retriever, honoring the place that dogs have always held in the tradition of waterfowling and the work they do to reduce crippling loss.

When John Olin heard about the choice of subject, he arranged to get in touch with Iowa artist Maynard Reece about the possibility of using King Buck in the art he would enter. Reece had already won two duck stamp competitions, and, as an avid hunter, was more than happy to take Olin up on the idea. Reece drove down to Nilo Kennels to meet Buck.

Photo SHOWMANSHOOTER.COM

"He was a well-mannered, intelligent dog," Reece later wrote, "and a good model. After 15 minutes, he went to the door and wanted out. The modeling session was over. I ended up using just his head and shoulders with a dead mallard in his mouth." The painting won the competition, and Buck, his muzzle graying with age, his dark eyes fixed on the horizon, provided the image that has defined duck dogs ever since.

Time is no friend to dogs or the people who love them. In the winter of 1962, Cotton could see that Buck was failing. John Olin knew the end was near and left the final decision to Cotton.

"He had arthritis and he was gettin' dehydrated," Cotton said. "You could see him shrinking, and it was gettin' kind of hard for him to get up in his doghouse. I just wasn't going to see the dog in that kind of shape." The vet put him down four days before his fourteenth birthday, a striking old age for a purebred dog that had suffered through such a rocky start. After Buck's death, Olin had him buried in front of the kennel. They raised a tumulus over the grave, like the burial site of a Viking warlord, and set a full-size statue of him on top. He was a king, after all.

Cotton went on to win another national open stake with Marten's Little Smoky in 1965. Altogether, he trained 28 field champion retrievers and won three national titles, but in a long life with working dogs, he never saw another like King Buck.

"I ain't seen a dog that could even smell where he's been," Cotton said of Buck. "Linin', handlin', runnin', or doin' anything else."

The dog was about as good as there ever was. So was the man. Together, they set the standard for a new generation of dogs and dog men. These days, whenever a Lab hits the water after a crippled mallard, huffing like an old steam engine, or sprints down a corn row in hot pursuit of a rooster pheasant, Buck is in his blood and Cotton is in his heart.

The most famous retriever of all time, King Buck passed away in 1962. A full-size statue marks his grave at Nilo Farms.

Photo SHOWMANSHOOTER.COM

King Buck at the Waterfowling Heritage Center

Photo John Hoffman/Ducks Unlimited

Learn more about King Buck, Cotton Pershall, and John Olin's Nilo Farms at the DU Waterfowling Heritage Center inside Bass Pro Shops at the Pyramid in Memphis, Tennessee. You can see some of King Buck's field-trial trophies and other memorabilia and watch rare historic footage of Buck and Cotton in action.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy