Decoy Spreads: River Chute Two-Spread Set

Learn about decoy spreads and the River Chute Two-Spread Set. Explore decoy placement strategies to attract waterfowl and create an effective hunting setup.

Learn about decoy spreads and the River Chute Two-Spread Set. Explore decoy placement strategies to attract waterfowl and create an effective hunting setup.

Mel DeLang has seen many sunrises from duck blinds in southeast Iowa. DeLang, from Burlington, guided for 40 years on the Mississippi River and the Lake Odessa Wildlife Area. He is also a former world champion duck caller (1963), and he has judged numerous duck calling contests, including three world championships.

Now in his sixties, DeLang has given up guiding and competition calling, but he still hunts every day of the season from a permanent blind on a chute just off the Mississippi River, the former Lakewood Hunting Club. This is a typical open-water setup, where the decoys are exposed to strong winds and currents. DeLang and his partners maintain three blinds, each of which is complemented with its own large, permanent spread of up to 300 decoys.

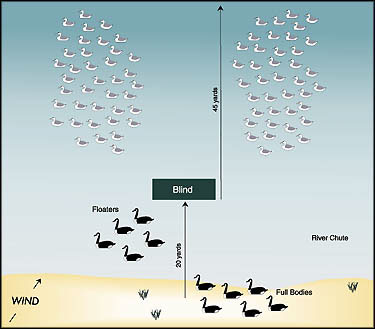

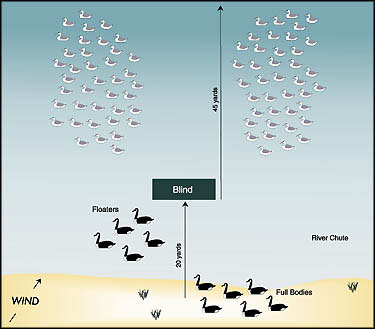

"We use this many decoys for greater visibility and to attract high, passing ducks," DeLang explains. "We use all super magnums, mostly mallards with a few pintails mixed in. Mallards are the main ducks we're hunting. Also, we set about 50 Canada goose floaters off to one side of the blind and another 75 standup full-body geese on a mud flat behind our main blind."

The river slough where DeLang hunts is approximately two miles long by 200 yards wide. It is totally open-no brush or trees. It is also shallow, two-and-a-half feet deep when the Mississippi River is at pool stage at Burlington. "The chute runs north and south, and our blind is just out in the water off the west bank," says DeLang.

DeLang hunts over what he describes as a two-spread setup. Basically, this is a separate, rounded decoy spread of equal size off each corner of the blind with an open "meat hole" in the middle. Decoys in each spread are concentrated within 45 yards of the blind. The goose floaters are set off the north back corner of the blind, between the ducks and the mudflat. Then, the standup geese are spread behind the blind on the mud.

"Our best winds for working ducks are northwest, west, and southwest, and with this setup they'll hook around and land in the open hole between the two spreads," DeLang explains. He adds that this setup doesn't work as well on an east wind, but the breeze blows rarely from this direction in southeast Iowa.

DeLang ties his decoys with heavy parachute cord and anchors them individually with home-poured concrete anchors "the size of a Styrofoam beer cup." He says the heavy weights are necessary for days when the wind or river currents kick up.

"I like to set each decoy individually instead of running them on long lines the way some open-water hunters do," DeLang continues. "I think the random spread looks more natural. I cut my anchor lines four feet long (again, for two-and-a-half feet of water), and I set my decoys two feet apart. This way, when the wind changes, all the decoys can swing together without tangling."

Two major problems with this type of spread are ice and rising water. "When ice begins forming, we start pulling decoys," DeLang says. "If it gets really icy, we'll pick up all the decoys, then put out what we want to hunt over each day. If we leave 'em out, ice floes will carry them down the river."

DeLang does likewise when the water level begins rising. "When the water comes up, logs and debris will snag our decoys and scatter them from here to St. Louis. So we keep a careful watch during a rise, and we pick up the decoys if we have to." DeLang has a system for quick decoy pickup. "I attach a snap swivel to each anchor, and when I pick up a decoy, I just unsnap the weight and then put the decoy in the pile without winding up the cord. Those heavy parachute cords won't tangle. This system is faster than wrapping the anchor and string around each decoy."

One thing DeLang is fastidious about in his open-water spread is keeping decoys untangled. "I hate the sound of decoys bumping together. With the way we rig our set, we usually don't get many tangles unless there's a big blow. But when tangles happen, I straighten them out. Tangles might not bother the ducks as much as they bother me, but I don't tolerate 'em!"

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy