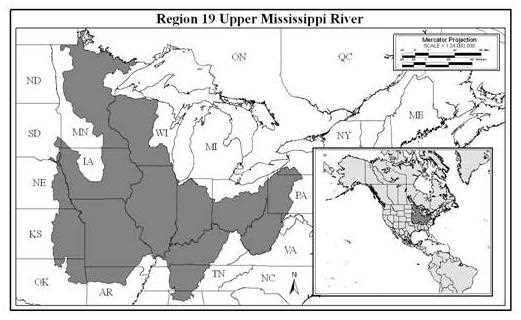

Upper Mississippi River

Level III Ducks Unlimited conservation priority area, providing a migration corridor for hundreds of thousands of dabbling ducks and significant numbers of divers

Millions of waterfowl rely on habitat along the Upper Mississippi River for breeding, migration and foraging habitat. This area provides a major migratory corridor for the Mississippi Flyway, which funnels more waterfowl to the wintering grounds than any other flyway. Habitat restoration and protection programs in the upper reaches of the watershed significantly improve water quality in the Mississippi River and impact waterfowl habitat as far south as the Gulf of Mexico. Through DU's Upper Mississippi Ecosystem Initiative, DU is working to conserve migratory habitat in the southern part of the initiative area, and breeding habitat in the north.

Importance to waterfowl

- The Mississippi River and its major tributaries provide a migration corridor for hundreds of thousands of dabbling ducks, and significant numbers of ring-necks, canvasbacks and scaup.

- Managed areas and restored bottomland forests provide wintering and migration habitat for mallards, black ducks, wood ducks, northern pintails and Canada geese.

- The Illinois River Valley provides some of the most significant mid-migration habitat for mallards in the Mississippi Flyway.

- The river systems in Ohio provide important migration and wintering habitat for mallards, black ducks and pintails.

- Wetland/grassland complexes provide beneficial breeding habitat for mallards and blue-winged teal.

Habitat issues

- The area has suffered the greatest wetland loss of the entire Great Lakes/Atlantic region.

- Timber harvest, levee construction and surface mining have altered habitat conditions for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife.

DU's conservation focus

- Conservation goals primarily focus on migratory issues in the southern parts of the initiative and on breeding issues in the northern area.

- Restore wetlands and associated grasslands on public and private land.

- Develop hydrological restoration and management systems that emulate natural conditions.

- Protect mid-migration habitat vulnerable to loss.

- Increase public awareness of the benefits of wetlands.

States in the Upper Mississippi River region

Alabama | Arkansas | Illinois | Indiana | Iowa | Kansas | Kentucky

Maryland | Minnesota | Missouri | Nebraska | New York | Ohio

Oklahoma | South Dakota | Tennessee | West Virginia | Wisconsin

Background information on DU's Upper Mississippi River conservation priority area

The Upper Mississippi River Waterfowl Conservation Region (Region 19*) includes portions of the Eastern Tallgrass Prairie, Prairie Hardwood Transition and the Central Hardwoods of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (IAFWA 1998). This region is bisected by the floodplain of the Mississippi River and its larger tributaries in all states of the watershed. The floodplains of the river systems include diverse wetland habitat, including temporarily and seasonally flooded bottomland hardwoods, permanently and semi-permanently flooded shrub and wooded swamps, emergent wetlands, mudflats and submerged aquatic beds, all of which are utilized by migrating waterbirds.

The Mississippi River and its major tributaries, the St. Croix, Chippewa, Wisconsin, and Rock Rivers, drain approximately 75% of Wisconsin's landscape. The Upper Mississippi River basin in Wisconsin has nearly 38,057 ha of riverine and bottomland habitat, 371 km river length, and almost 3,226 km of shoreline (USFWS 1998). This region provides important wildlife habitat and is vital to maintenance of water quality. Southeast Wisconsin contains the largest cattail marsh in the U.S., Horicon Marsh. Horicon Marsh is nearly 12,955 ha in size and is designated a RAMSAR Wetland of International Importance. Additionally, more than 35,830 ha are protected under public ownership in the Mississippi River and Trempleau NWRs.

Except for a small portion of the Chicago metropolitan area, all of Illinois occurs in the watershed of the Mississippi River. Approximately 90% of historic wetlands of Illinois have been lost (Dahl 1990). A major portion of Illinois that drains into the Mississippi River comes through the Illinois River Valley. Prior to settlement, the Illinois River basin contained approximately 141,700 ha of wetlands, but now less than 68,826 ha remain due primarily to drainage for agriculture. State and federal management areas protect 6,680 ha of existing habitat, and private duck clubs have secured an additional 6,478 ha (USFWS 1998). Because 80% of the watershed is used for agriculture, high erosion rates have impacted terrestrial and aquatic waterfowl habitat as well as water quality.

The Mississippi River Valley in southern Illinois contains more than 137,651 ha of wetlands. Along the Cache River, swamps, bottomland forests, limestone glades and success ional fields provide habitat for over 250 species of migratory waterfowl, wading birds and Neotropical migrant songbirds (USFWS 1998). This area has been designated as a wetland of international importance by the RAMSAR convention. Black Bottom, located at the southeastern tip of Illinois on the north side of the Ohio River contains low gravel hills with continual groundwater seeps. The area is rich in a diversity of unique flora, including cypress swamps, flood plain forests and rare species of orchids, mosses and ferns. Predominantly in private ownership, this unique wetland complex should be preserved for its integrity and benefit to all types of wetland bird species. Timber harvest, levee construction and surface mining have altered habitat conditions for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife in this region of Illinois.

Wetland loss in Indiana has been extreme with only 15% of the state's pre-settlement wetlands remaining (Dahl 1990). Clearing bottomland forests in southwest Indiana has been the primary impact on wetland habitat. Few flood control levees exist in southern Indiana, allowing rivers to flood over their banks and into the bottomlands in spring and fall. However, frequency and intensity of flooding events have been affected by agricultural and other human development. Threats to wetlands in this area include agricultural activities, commercial and residential development, road building, water development projects, timber harvest, mining, groundwater withdrawal and vegetation removal and sedimentation.

In addition to being dominated by the large river systems of the Ohio, Wabash, White and Patoka, the Indiana portion of this region also includes the Kankakee River basin in northeast Indiana, which once supported one of the largest freshwater wetland complexes in the U.S. (USFWS 1998). Known as the Grand Kankakee Marsh, this area once encompassed over 202,429 ha of prime waterfowl habitat. Wetland and prairies were intertwined with the Kankakee River as it meandered from South Bend, Indiana to the Illinois state line, taking a 387 km course to cover the 121 km distance. Channelization and drainage to support agriculture have resulted in the loss of nearly the entire marsh.

*Region 19 - NABCI Bird Conservation Regions 22, 23 & 24 (E astern Tallgrass Prairie, Prairie Hardwood Transition, Central Hardwoods)

Several areas of importance in Ohio are the Killdeer Plains/Big Island Wetland Complex and the watersheds of the Scioto, Great and Little Miami, and Muskingum Rivers. The Killdeer Plains/Big Island Wetland Complex was originally the eastern-most extension of a large wetland and prairie complex that consisted of prairie pothole and oak savanna habitats. This region has been extensively drained and converted for agriculture. The Scioto River is a major tributary to the Ohio River, and its valley is a mosaic of broad floodplains, small streams, agricultural land, and bottomland forests. Much of this region has been cleared and drained for agriculture giving it a high potential and priority for restoration.

Minnesota and Iowa are also important areas once dominated by lakes and wetlands. Loss of wetlands and grasslands has diminished the waterfowl production capacity of this landscape, however it continues to provide vital waterfowl migration habitat that includes large marshes and shallow lakes on the prairie to natural wild rice wetlands in the forest. The large wetlands remaining serve as a vital link between southern wintering grounds and breeding areas to the north and west. During prairie droughts, more permanent water in Minnesota's lake country offers refuge to displaced waterfowl. Although direct drainage no longer threatens these wetlands, recent research suggests that productivity in these wetlands has seriously declined and may be directly impacting waterfowl populations.

In Missouri and eastern Kansas, important migration and winter habitat occurs along the Missouri River and its major tributaries, including the Osage and Grand River systems. However, wetlands associated with these river systems have been severely degraded as a result of the effects of flood control and navigation projects. These projects dramatically altered natural hydrology of these rivers, and they have created disconnects between the rivers and their floodplains where most of the valuable wetland habitat was located. Subsequent to alterations of hydrology came conversion of many former wetland areas to agriculture and other uses. The net effect has been a reduction in waterfowl carrying capacity in the region.

Importance to waterfowl

Mallard nesting activity occurs throughout the Eastern Tallgrass Prairie, Prairie Hardwood Transition and the Central Hardwoods regions where there is suitable habitat, though little quantitative information is available. Wetland/grassland complexes provide beneficial breeding habitat for mallards and blue-winged teal. The bottomland hardwoods provide some of the best wood duck nesting and brood rearing habitat in the Upper Mississippi River Conservation Region. The breeding wood duck population in the Illinois River Valley is estimated at 20,000 (USFWS 1998). The Horicon Marsh and surrounding area provides some mallard and blue-winged teal production. Horicon supports the largest redhead breeding population east of the Mississippi River (WDNR 1973).

The Mississippi River and its major tributaries provide a major migration corridor for hundreds of thousands of dabbling ducks, and significant numbers of ring-necks, canvasbacks and scaup (USGS 1999). Managed areas and restored bottomland forests in the Eastern Tallgrass Prairie, Prairie Hardwood Transition and the Central Hardwoods regions provide wintering and migration habitat for mallards, black ducks, wood ducks, northern pintails, Mississippi Valley Population of Canada geese and other species. Horicon Marsh is a major migration stopover for the Mississippi Valley Population of Canada geese, with between 100,000 and 500,000 geese utilizing the marsh as they make their way from northern breeding grounds to wintering habitat in southern Illinois (Bellrose 1980). The Illinois River Valley and associated wetlands provide some of the most significant mid-migration habitat for mallards in the Mississippi Flyway, often peaking at over one million in the fall. Although not to the magnitude as the Illinois River, the River systems in Ohio provide important migration and wintering habitat for mallards and black ducks and other species crossing from the Atlantic coast, such as pintails.

The Missouri River and its major tributaries provide important migration habitat for mallards, green-winged teal, wood ducks and other puddle ducks, as well as Canada and snow geese. In years of mild winter weather, several hundred thousand waterfowl, particularly mallards, may over-winter in habitats associated with the Missouri River.

Current conservation programs

Within this Waterfowl Conservation Region, there area several significant areas in which DU delivers conservation programs. These include the Ohio Rivers area, Illinois River watershed, southeast and northwest Wisconsin, the Living Lakes area (MN and IA), and programs in Missouri.

The Illinois River watershed is a significant migration corridor. The number of mallards migrating through the valley has decreased by 65% and the number of divers, especially lesser scaup, have decreased by more than 90%. Despite these declines, 25% of all ducks I the Mississippi Flyway still use the Illinois River as a migratory corridor. The degradation of the system has also resulted in major non-point source pollution input to the Mississippi River ecosystem. Other significant areas in Illinois include the Rock River watershed for production and the confluence of the Ohio/Mississippi Rivers in southern Illinois and Indiana. In Illinois, the priority should be on diving duck migration habitat (fall and spring) mostly in the middle reach of the Illinois River. The second priority will be spring habitat for both dabblers and divers, and finally production in the upper reaches near Wisconsin.

Concentration areas in Wisconsin include the southeast and northwest parts of the state and conservation work is primarily focused on production, although these areas also provide important migratory habitat. The northwest area was historically dominated by pothole-type wetlands and the southwest area historically characterized by a glaciated mosaic of wetlands surrounded by tall grass prairie and oak savanna. Agriculture and urban development have resulted in substantial wetland loss, fragmented grasslands and increase sediment and nutrient loading to streams and rivers in both areas. The conservation focus in Wisconsin is on protecting and restoring small seasonal wetlands and re-establishing native prairie adjacent to wetlands for production and spring migratory habitat, and expansion of existing state and federal wildlife areas for fall habitat.

In Minnesota and Iowa, the Living Lakes initiative targets spring migratory habitat for multiple waterfowl species. The focus is to establish stepping stones of perpetually protected and managed wetland complexes for Keokuk Pool in southwestern Iowa through northern Minnesota that will provide waterfowl with the necessary food and habitat resources as they travel across this migratory pathway. This will be accomplished through shallow lake watershed improvements, shoreline protection and acquisition, and shallow lake and large marsh restoration, enhancement and protection.

The Scioto, Muskingum, and Miami River watershed s are currently being evaluated for the migration and wintering habitat benefits they provide. These river systems serve as primary migration corridors for tens of thousands of waterfowl between Lake Erie and the Ohio River, as well as waterfowl species traveling west from the Atlantic coast. Several thousand mallards, black ducks and Canada geese winter along these rivers, feeding in the rich agricultural fields lining the river valleys.

Conservation programs in Missouri and eastern Kansas also fall within the boundaries of the Upper Mississippi River Waterfowl Conservation Region. The focus of programs in Missouri and Kansas is on protection, restoration and development of migration habitat for waterfowl following corridors along major rivers such as the Marais des Cygnes, Kansas, Osage, Neosho, and Missouri and their major tributaries. To date, conservation efforts have been project-specific and include notable works at Marais des Cygnes Wildlife Area in Kansas, and Four Rivers and Grand Pass Conservation Areas in Missouri.

Goals

- Restore and protect wetlands and associated habitats that benefit waterfowl, wildlife, and people, improve water quality, and promote watershed health.

- Provide habitat of sufficient quality and quantity so to not be limiting to wintering, migrating and breeding waterfowl populations.

- Target wetland and lake restoration activities to provide adequate food resources to spring migratory waterfowl.

- Along river systems, aim for interconnected natural habitats of old-growth timber, buffered waterways, emergent flood plans, and complexes of wetland types by restoring Hydrology to the extent possible.

- Develop GIS targeting tools and the research needed to address current uncertainty in the life cycle needs and limitations of key waterfowl species within the Upper Mississippi Watershed.

Establish outreach programs to educate the public on the importance of wetland values and a healthy environment. - Evaluate the role of DU in regard to expanded conservation programs throughout the region, including: a) formation of new partnerships; b) provision of biological and engineering services to agencies and private landowners; c) development of partnership-driven private lands programs; and d) proactive use of conservation easements to protect habitat.

Assumptions

- Foraging habitat limits populations migrating through or wintering in the region.

- Wetland and grassland restorations provide all the habitat elements needed for successful reproduction and provide sustainable benefits.

- Wetlands and grasslands will continue to be restored, enhanced and managed to maximize productivity for waterfowl and other wildlife by state and federal agencies.

- Wetland restoration activities are additive towards improving water quality problems in the Mississippi River system and improving food resources for waterfowl.

Strategies

- Restore wetlands and associated grasslands on private land, utilizing Farm Bill Programs such as WRP, CRP and CREP, DU Private Lands Programs and NAWCA.

- Develop hydrological restoration and management systems that emulate natural conditions.

Maximize mid-migration habitat through the protection of habitats that are vulnerable to loss through acquisition, conservation easement or long-term management agreements and other cooperative land protection programs. - Increase public awareness of DU's programs and the benefits to wetlands they provide by developing public relations plans for regional conservation programs.

- Restore wetlands and associated grasslands on public land.

- Incorporate management capability into restored wetlands to maximize wetland productivity for waterfowl and other wetland wildlife.

- Expand wetland conservation programs to watershed or landscape levels - targeting water quality as a major issue/benefit.

Restore bottomland hardwood forests in concert with moist soil management units and enhancement of shrub/scrub wetlands to provide food resource benefits to migrating and wintering waterfowl. - Develop shallow water habitat to benefit the large numbers of waterfowl that frequent flooded agricultural fields during spring migration.