North Atlantic / New England Coast

Level III Ducks Unlimited conservation priority area, major wintering area for Atlantic Flyway brant, scaup, black ducks and bufflehead

Coastal and inland wetlands along the Atlantic coast have been recognized as an important ecological resource, not only for waterfowl, but wading birds, shorebirds and other aquatic species that depend upon coastal marshes during their lifetime. Within the mid-Atlantic region, a substantial number of salt marshes have been lost during the past 200 years. Between 1954 and 1978, loss rates were extremely high primarily due to urban and industrial development. However, since the passage of protective legislation, loss rates have declined dramatically. The focus of DU's conservation programs in the region is on meeting the needs of migratory and wintering waterfowl by restoring and conserving coastal watersheds.

Importance to waterfowl

- The most common nesting species in this initiative are mallards, black ducks and Canada geese.

- Coastal wetlands in Maine are used extensively by black ducks, sea ducks and geese during winter and migration.

- The majority of Atlantic Flyway populations of brant, greater scaup, black ducks and bufflehead winter in southern New England and the New York bight.

- About one-third of the entire Atlantic Flyway population of wintering black ducks can be found in the New York bight.

Habitat issues

- The New England Coast is one of the most populous and heavily industrialized coastal areas in the world.

- Remaining coastal wetlands are subject to extreme social and economic pressures.

DU's conservation focus

- Meet the needs of migratory and wintering waterfowl by restoring and conserving coastal watersheds.

- Breeding objectives for mallards and black ducks.

- Efforts to restore wetlands and associated habitats will be focused in the coastal areas.

- Establish public education programs on the importance of wetland values and a healthy environment.

States in the North Atlantic / New England Coast region

Connecticut | Maine | Massachusetts

New Hampshire | New York | Rhode Island

Background information on DU's North Atlantic / New England Coast conservation priority area

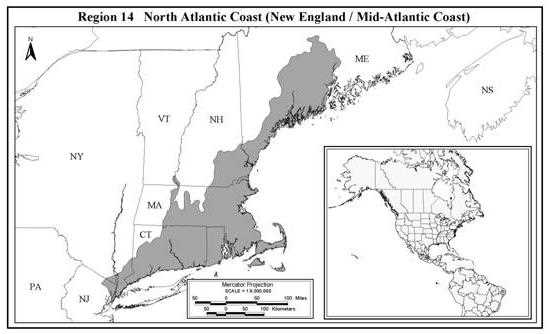

The North Atlantic Coast Waterfowl Conservation Region (Region 14*) includes the portions of the Atlantic Northern Forest and the New England/Mid-Atlantic Coast Ecoregions identified by the Commission for Environmental Cooperation (IAFWA 1998). A chain of extensive estuarine embayments characterizes the North Atlantic Coast , stretching from Long Island Sound, to Scarborough Bay in Maine . The complex geology and geography of the Atlantic coast creates a remarkable diversity of highly productive shallow water and adjacent upland habitats including barrier beach and dune, submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) beds, intertidal sand and mudflats, salt marsh islands, fringing tidal salt marshes, freshwater tidal marsh, and maritime forest. Major river systems drain into estuaries, merging into a network of tidal channels and bays, before ultimately flowing into the Atlantic Ocean . Inland habitats include coastal plain intermittent ponds, hardwood and Atlantic white cedar swamps, upland forests, and agricultural areas.

Coastal and inland wetlands along the Atlantic coast have been recognized as an important ecological resource, not only for waterfowl, but wading birds, shorebirds and other aquatic species that depend upon coastal marshes during their lifetime. Within the mid-Atlantic region, a substantial number of salt marshes have been lost over the past 200 years. Between 1954 and 1978, loss rates were extremely high primarily due to urban and industrial development. However, since the passage of protective legislation, loss rates have declined dramatically. Remaining tidal marsh is fairly well protected, but is severely degraded due to past grid-ditching activities. This practice resulted in altered hydrological patterns, lowered water tables, and invasion of exotic species such as common reed and purple loosestrife. Although coastal wetlands are under protection, protection of inland wetlands is not as effective. Pressure on inland wetlands and adjacent uplands continues to grow due to increases in human populations desiring proximity to coastal areas. The Atlantic coast is the most populated and heavily industrialized coastal area in the world. Industrial and agricultural runoff from major river systems continues to pose a threat to coastal waters and tidal marshes. This development trend continues today with grave consequences for coastal habitats and the wildlife that depend upon those systems.

Atlantic estuaries are a major link in the migratory chain that stretches from South America to Canada. The significance of this complex of habitats relates to its geographic location, which acts to concentrate migratory marine and estuarine species along the coastlines in both directions. The majority of Atlantic flyway populations of brant, greater scaup, black ducks, and bufflehead winter in southern New England and the New York Bight. About 1/3 of the entire Atlantic flyway population of wintering black ducks can be found in the New York Bight. Further, 80% of the wintering population of Atlantic brant are found in New Jersey and Long Island . The most common nesting species in this initiative are mallards, black ducks, and Canada geese. Conservation efforts in along the North Atlantic coast focus on migratory and wintering waterfowl needs, as well as breeding objectives for mallards and black ducks.

*Region 14 - NABCI Bird Conservation Regions 14 & 30 (Atlantic Northern Forest, New England/mid-Atlantic Coast)

Importance to waterfowl

Expansive estuarine and near-shore habitats along the Atlantic coast historically provided abundant SAV and animal foods (including clams, snails and other invertebrates) used by waterfowl (Peterson and Peterson 1979). Tidal and riverine freshwater and brackish emergent marshes provide sheltered resting areas for wintering ducks and geese (Gordon et al. 1989).

Areas of historical importance to waterfowl in the North Atlantic coast include significant habitats found along the Connecticut River, in Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island , along the Merrimack River and Plum Island Sound in Massachusetts , the Great Bay estuary in New Hampshire , and Merrymeeting and Cobscook Bays in Maine.

Waterfowl migrate in substantial numbers down the Hudson and Connecticut Rivers and/or along the Atlantic Coast , stopping to rest and feed in coastal bays and wetlands. For several species, such as brant, greater scaup, black duck, and bufflehead, the mid-winter populations occurring in the southern New England - New York Bight account for a major part of their total Atlantic flyway populations. The New York Bight accounts for about one-quarter of the Atlantic flyway wintering population of buffleheads ( USFWS 1997). Coastal wetlands in Maine are used extensively by black ducks, sea ducks and geese during winter and migration, especially Merrymeeting and Cobscook Bays . In addition, large concentrations of scoters raft off the shoals of Nantucket and Cape Cod in Massachusetts (Bellrose 1980).

During 1986-1990, 72% of all black ducks wintered in the Atlantic Flyway. About one-third of the total Atlantic flyway population of black ducks winters in the New York Bight. Wintering black ducks are found in bays, marshes, and flats along the Hudson River, New York Harbor.

Importance to other wildlife

The wetlands of North Atlantic estuaries, and the riverine wetlands of tributary streams and creeks, provide spawning, nursery, and feeding sites for a multitude of fish and shellfish species. The lower Hudson River Estuary is a major nursery area for striped bass, white perch, and tomcod that spawn elsewhere in the Hudson River system. In addition, the river is a wintering area for the federally listed endangered shortnose sturgeon.

Coastal and inland wetlands provide critical habitats for waterfowl, wading birds, and shorebirds, as well as other wildlife. Every spring and fall, wetlands and beaches of the estuary host massive migrations of shorebirds, waterfowl, raptors and songbirds. All types of natural habitats, including marshes, fields, successional habitat, and woods, are used by fall migrants, although woodlands adjacent to salt marshes seem to be particularly important. Black Guillemots breed in Maine 's coastal habitat, while Leach's storm petrels, gulls, terns, and the southernmost population of breeding alcids nest on off-shore islands.

Threats and special problems

The New England Coast is one of the most populous and heavily industrialized coastal areas in the world. Much of the upland and wetland shoreline of the major Atlantic bays and their watersheds have been developed, impaired, or degraded by industrial, commercial, and residential uses. Wetland losses have resulted from coastal impoundment and filling, dredging projects, and natural sea level rise. Urban development has resulted in substantial wetland loss and has accelerated the rates of erosion along shorelines that have been stripped of vegetation. Remaining coastal wetlands are subject to extreme social and economic pressures. Ecological impacts from urban and suburban development include point and nonpoint source pollution, oil and chemical spills, recreational overcrowding, floatable materials, atmospheric fallout of pollutants, dredging and dredged material deposition, over harvesting of fishery resources, competition from exotic and invasive species, and destruction of essential natural habitats (USFWS 1997).

In addition, significant wetland losses are attributable to conversion of nontidal, forested wetlands to agriculture (USFWS 1988). All of the Atlantic states have enacted laws and regulations to protect coastal wetlands. However, protection of inland wetlands has not been as effective. In addition, pressures on adjacent uplands continue to grow with increases in human populations seeking proximity to the coast.

Current habitat conservation programs

The focus of conservation programs in the North Atlantic is on meeting the needs of migratory and wintering waterfowl by restoring and conserving coastal watersheds. The primary goal is to restore hydrologic function to degraded coastal wetlands by addressing invasive species, removing tide gates, replacing undersized culverts, removal of roadbeds and dikes, and removal of dredge spoil or fill material. Efforts to restore wetlands and associated habitats will be focused in the coastal areas.

Goals

- Restore and protect ecological functions and values of coastal watersheds.

- Protect and maintain grass, tree and shrub buffers around the existing marshes.

- Gain a better understanding of the geographic distribution of waterfowl needs.

- Target areas where complexes can be built on existing and/or protected habitat.

- Establish public education programs on the importance of wetland values and a healthy environment.

Assumptions

- Restoring tidal hydrology, via ditch plugging, restores function and habitat value to coastal marshes

- Restoration work in the headwaters will improve habitat by improving water quality in the coastal marshes

- Restoration of coastal habitat will improve survival of wintering waterfowl or increase carrying capacity

- Coastal restoration activities designed for migratory or wintering waterfowl will also benefit breeding waterfowl

- A working assumption is that fall and spring coastal habitat for waterfowl is not different

Strategies

- Protect and enhance coastal and riverine marshes, shallow bays and adjacent upland areas along New England using a 'complex concept': restoration of wetland, upland, and riparian habitats located in or near permanently protected habitats.

- Re-create open water habitat, such as deeper pools and shallow pannes, to provide protective and productive foraging areas for waterfowl, game fish, baitfish, and migrating shorebirds and wading birds.

- Restoration should focus on restoring tidal hydrology to wetlands that have been altered by roadways, railway lines and historic grid ditching.

- Focus on restoring buffers adjacent to the marshes to improve water quality that negatively affects the salt marsh system.

- Continue cost-sharing the long-term control of invasive species, such as common reed and purple loosestrife.

- Partner with other groups and agencies to promote wetland conservation, management and protection.