Falling Snows

After soaring to record highs, midcontinent light goose populations have declined dramatically in recent years

After soaring to record highs, midcontinent light goose populations have declined dramatically in recent years

By Mitch D. Weegman, PhD; Kevin Kraai; and Mike Brasher, PhD

The sights and sounds of snow and Ross’s geese—collectively known as light geese—thundering into the air from overnight roosts and spiraling down like white tornados into croplands are among the greatest spectacles on Earth. From the shores of Hudson Bay to the Gulf Coast, hunting these majestic birds is among waterfowling’s most exhilarating and challenging experiences.

Interest in hunting light geese increased dramatically in the 1990s, coinciding with liberalized harvest regulations that had been implemented to help curb their rapidly increasing numbers. However, recent data suggest that these populations have now collapsed to levels not seen in nearly 30 years. Researchers are hard at work diagnosing the causes of this recent population crash and studying implications for future management of these birds. This article examines recent trends in light goose numbers and offers insights into what may lie ahead. We also hope to inspire a new narrative around these incredible birds, as they have challenged our brightest scientific minds and deserve our respect and admiration.

Snow and Ross’s geese are among the world’s largest populations of geese. In North America, there are three populations of light geese, which are monitored and managed independently. The midcontinent population consists of lesser snow and Ross’s geese that nest across the central Arctic and subarctic and migrate and winter primarily in the Central and Mississippi Flyways. The western population nests in the western Arctic and far eastern Russia, wintering in coastal states of the Pacific Flyway, where they commingle with Ross’s geese from the midcontinent. Greater snow geese nest in the eastern Arctic and winter in states along the Atlantic Coast. Each population presents its own unique history and modern management challenges. However, the midcontinent population has experienced the most dramatic population swings over the last 35 years.

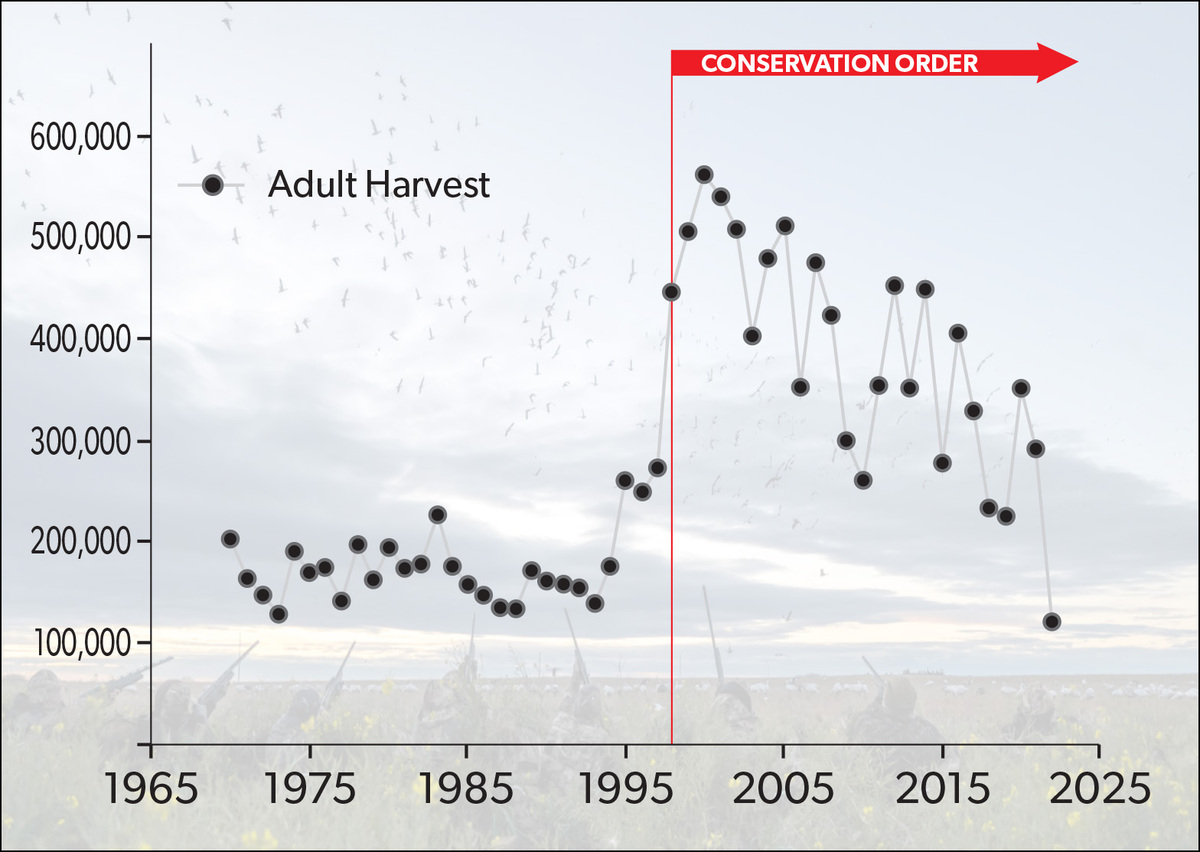

After increasing sharply when the Light Goose Conservation Order was implemented in 1999, annual harvests of adult midcontinent lesser snow geese have been trending downward. Photo: Michael Clingan/Montana Outdoor Imagery

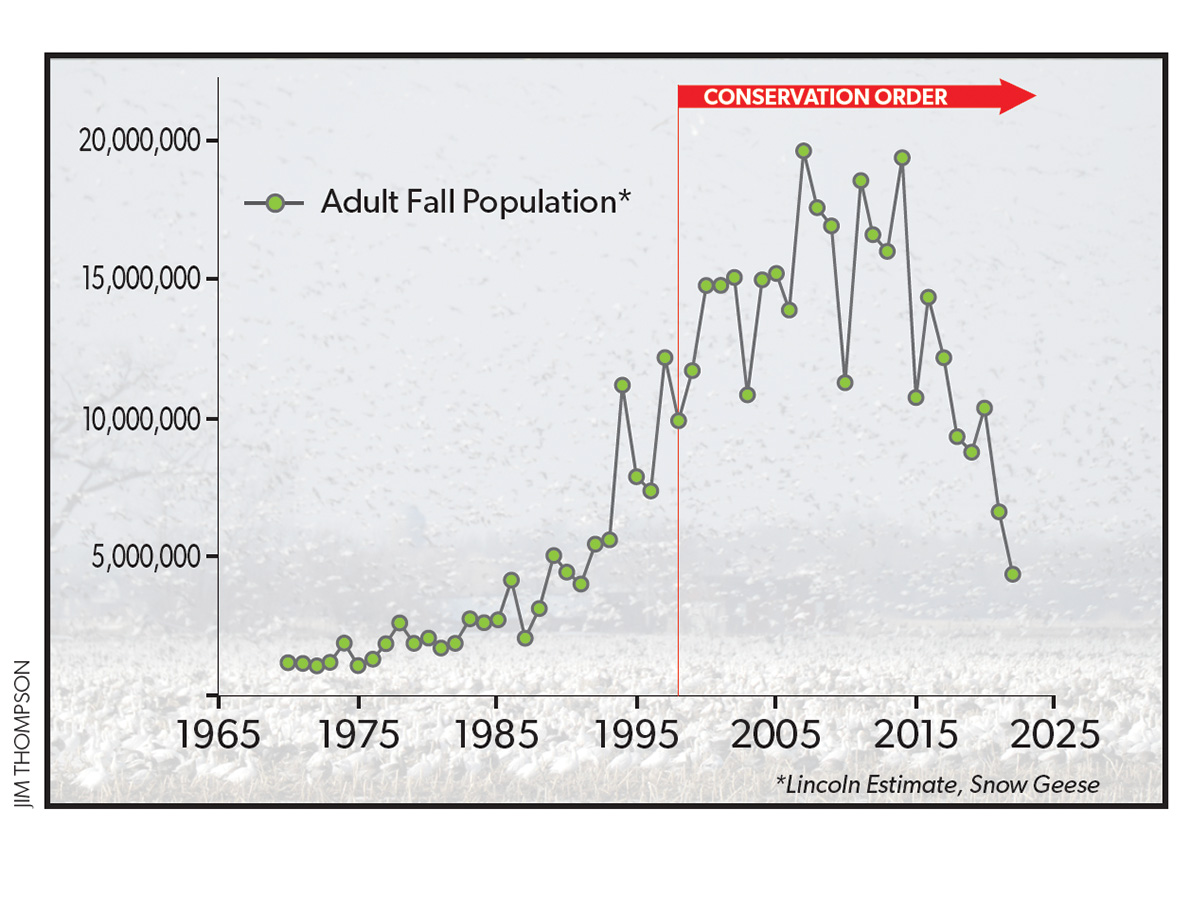

Researchers believe that there were just over 4 million adult midcontinent light geese during the early 1990s. The population grew exponentially during the 2000s, peaking at around 20 million by 2007. The rate of population growth was so extreme that biologists worried that feeding behaviors of hyperabundant light geese would irreparably damage fragile Arctic and subarctic ecosystems, threatening other populations of wildlife.

Population modeling, coupled with observations of worsening goose impacts on breeding areas, prompted the US and Canadian governments to pass legislation in 1999 that provided unprecedented opportunities to harvest light geese outside of the normal frameworks of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. Known as the Light Goose Conservation Order (LGCO), its primary objective was to decrease adult survival rates to reduce and maintain light goose populations at acceptable levels. Federal, state, and provincial managers collaborated to develop population and harvest rate thresholds that would be used to monitor whether the conservation order was effective.

Although harvest rates and total harvest increased immediately following implementation of the LGCO, the levels were insufficient to slow the growth of midcontinent light geese. The population continued to increase over the next decade, but that trajectory changed in the early 2010s, as researchers documented consecutive years of population decline. The decline has continued unabated, with around 6 million adult light geese estimated in the midcontinent population as of 2022. This equates to a 70 percent decline from its peak, and it represents the steepest decline of any North American waterfowl population in recent history.

Hunters in the Central and Mississippi Flyways might question these estimates, as fields filled with tens of thousands of light geese are still common in migration and wintering areas. Yet evidence of the decline is supported by multiple data sets. Continental estimates are obtained using the Lincoln-Petersen estimator, which uses harvest rate and total harvest to calculate population size. The decline is mirrored by contractions in the physical size and number of nesting geese at the historic Karrak Lake snow goose colony in the central Arctic. The ratio of juveniles to adults in Arctic and subarctic banding operations also shows this trend.

Waterfowl managers have calculated recent declines in light goose populations in part by analyzing band return data reported by waterfowlers. This information has also revealed that light goose harvest rates have remained below management objectives.

The rise and fall of midcontinent light geese is a remarkable story of waterfowl ecology in a changing world, and one that is currently the focus of intense study. Historically, light geese wintered in the coastal marshes bordering the Gulf Coast, where they fed on short grasses and sedges that were relatively limited in abundance, and it is believed that these food sources restricted their population size. Over time, snow and Ross’s geese learned that waste grain in harvested rice, corn, and wheat fields was highly accessible and provided an abundance of calories. Feeding on these rich food sources across vast landscapes allowed the birds to return to their tundra breeding areas in optimal condition for reproductive success. The result was an extended period of exceptional productivity, as millions of young light geese were produced and added to the population, fueling its growth.

What changed? Growth or decline of wildlife populations is often due to changes in survival (the percentage of birds that survive from one year to the next) or productivity (the ratio of juveniles to adults in the population each year). Reducing adult survival was originally identified as the best method for potentially controlling midcontinent light geese. Despite numerous studies that have looked for links between harvest rate, survival, and changes in population size over the last 35 years, none have been identified.

Since implementation of the LGCO, harvest rates of adult midcontinent snow geese as a percentage of the total population have changed little, hovering around 2 to 3 percent. Likewise, adult survival rates have barely budged and have even increased in recent years. In short, the LGCO has been unsuccessful in reducing adult survival—the primary vital rate it was designed to affect—and changes in survival or harvest are not responsible for recent population declines. With this knowledge in hand, our focus shifts to productivity.

With an abundance of agricultural food resources on migration and wintering areas and low harvest rates, survival remains high for adult lesser snow and Ross’s geese and has even increased in recent years.

Thanks to decades of band recoveries and harvest surveys from hunters, along with field data collected by government scientists and university faculty at long-term Arctic and subarctic research stations, known as “goose camps,” we have ample information to examine trends in productivity. Detailed analyses have found that annual changes in light goose productivity have the strongest effect on overall population change.

Agricultural waste grain remains an abundant food source for geese across the midcontinent today, providing opportunities for light geese to build nutrient reserves en route to their breeding areas. But that factor alone isn’t enough to guarantee high productivity. The Arctic summer is short, and geese face a narrow window of time in which to lay and hatch a clutch of eggs and raise their goslings before flying south. Adverse weather conditions or even slight disruptions in the timing of these activities can severely impact goose productivity. Goose hunters are familiar with the results of strong production years, which bring an abundance of juveniles that are easier to decoy.

If you’re a hunter in the Central or Mississippi Flyway, you have probably seen fewer juvenile light geese in recent years. According to data from summer banding operations in the Arctic and fall surveys in Prairie Canada, fewer juvenile snow and Ross’s geese have been produced in the midcontinent population over the last decade. The reasons for this poor productivity are not completely understood, but most evidence points to changes on their breeding areas. Temperature data show that the Arctic is warming much faster than more southerly areas. Arctic-nesting birds time their movements to coincide with the anticipated green-up of vegetation, because early plant growth is most nutritious for gosling growth and survival. With spring temperatures warming earlier, green-up is also happening earlier. Meanwhile, snow and Ross’s geese have been unable to sufficiently alter their dates of arrival and hatching to coincide with these changes. As a result, the timing of peak gosling hatch is no longer aligned with green-up, compromising their access to optimal nutrition and reducing gosling body condition and survival.

In addition to banding geese, waterfowl biologists based at research stations in the Arctic and subarctic monitor annual breeding success among light goose populations. Researchers believe that a recent decline in productivity is the main cause of decreasing light goose numbers.

Arctic summers are also changing rapidly. Warming sea temperatures are contributing to an increase in precipitation during summer, which often falls as cold rain that can last several days. Goslings are particularly vulnerable to rain and cold weather because their downy feathers provide only limited thermal protection and do not repel water. Storms that occur early in the lives of goslings can result in mass mortality, essentially wiping out all production for the year. Moreover, researchers have discovered that adult birds have been arriving on breeding areas in recent years with lower protein and fat reserves, which contributes to smaller clutch sizes and lower nesting success.

The effects of these phenomena are more than conjecture. Multiple data sets show declining productivity for midcontinent snow geese—measured as the ratio of juveniles to adults—while also revealing a dramatic disparity in age ratios between hatching and summer banding, when goslings are nearing flight. This highlights the severe impact of adverse weather on fall age ratios. These data also show that productivity has been exceptionally low for several years and that reproduction has been insufficient to offset the number of birds dying during those years, ultimately contributing to year-over-year population declines.

After peaking at approximately 20 million birds in 2007, the midcontinent lesser snow goose population declined to less than 5 million in 2022. This represents one of the most dramatic declines of any waterfowl population in recent history.

What about previous reports that geese are destroying their Arctic and subarctic ecosystems? There is no doubt that intensive grazing by once hyperabundant lesser snow and Ross’s geese has changed the areas where they breed and stage across the north. Portions of western Hudson Bay that served as both staging and breeding areas, such as La Pérouse Bay, incurred local ecological change. But it is apparent that widespread damage did not materialize as once feared, and the most intense damage was localized. Scientists believe this is because the Arctic and subarctic ecosystems that can support light geese are massive—larger than the scale of what even millions of birds might alter. Further, some damaged areas are expected to recover, albeit over decades.

Given this new understanding, it is reasonable to wonder about the future of light goose populations and the LGCO. Management of Arctic-nesting geese is guided by detailed plans that are collaboratively produced by federal, state, and provincial biologists. For midcontinent light geese, the plan identifies thresholds for harvest rates and population size that determine when management actions should be implemented or modified. In 2024, one threshold was crossed for lesser snow geese—the three-year running average of population size (4.74 million) dipped below 5 million. Both harvest rate and population size thresholds must be crossed simultaneously to trigger alternative harvest regulations, and this has not yet happened. Nevertheless, states or provinces may decide independently whether to participate in the LGCO. In 2024, Texas became the first state to withdraw from the conservation order, citing continental declines and severe, long-term losses of light geese from regions of their state, which has a rich goose-hunting culture. No other state has followed suit.

In positive news, light geese do not appear to have caused significant long-term damage to their fragile tundra breeding habitats as many waterfowl managers had feared.

Whether population declines will continue to levels that trigger more restrictive regulations is unclear. Light geese remain among the most abundant geese in North America and are capable of rapid population growth when conditions allow. For example, midcontinent light goose productivity rebounded in 2023 and 2024, when juveniles made up 20 to 30 percent of birds surveyed in Prairie Canada during fall. Emerging issues, such as highly pathogenic avian influenza, further complicate this picture. Outbreaks of avian influenza on staging and wintering areas over the past three years caused widespread illness and mortality among snow and Ross’s geese. Mortality appears to have been greatest among juvenile birds, potentially wiping out much of the recent increase in production. Meanwhile, researchers continue to explore other factors that may contribute to population and productivity declines, including body condition of birds during spring migration.

Waterfowl scientists are encouraged by the continued interest in these fascinating birds from researchers, hunters, and other waterfowl enthusiasts. These unique developments also encourage reflection on the value of long-term research and data to inform our understanding of the population dynamics of snow and Ross’s geese as well as other waterfowl species. Long-term commitments among researchers and conservation practitioners are rare in studies of the natural world, and they offer a point of pride for all who care about these birds. Continued collection of these data will be vital to maintaining our understanding of population dynamics and informing science-based management. We will continue to report on the complexities of light goose populations as new knowledge is developed. In the meantime, whether you enjoy watching light geese over decoys or with a cup of coffee on your back porch, take in the amazement, wonder, and mystery of these terrific birds with the confidence that the waterfowl management community has their best interests at heart.

For at least 100 years, researchers and biologists have studied snow and Ross’s geese at remote nesting colonies across the Canadian Arctic and subarctic, where they have gained unparalleled knowledge about the breeding biology of these birds and the ecosystems they inhabit. The challenges of living and working at Arctic field camps are immense, often requiring months of preparation. The men and women who have staffed these remote Arctic outposts are true conservation pioneers. From Dewey Soper’s intrepid expeditions to Baffin Island to study blue phase lesser snow geese in the 1920s to Ray Alisauskas’s influential research at Karrak Lake, the ongoing work at these camps has helped establish North American goose management as a worldwide gold standard for science-based decision-making with long-term data.

Most of these goose camps remain operational, made possible by support from government agencies and other partners. Researchers at the camps have banded over 1 million geese and led or co-led more than 700 peer-reviewed scientific articles. In addition to hosting seasoned researchers, the camps have trained hundreds of young professionals in Arctic field research. For more information about these legendary goose camps, visit agjv.ca/history-of-goose-field-camps-in-northern-canada/.

Dr. Mitch D. Weegman is the Ducks Unlimited Canada endowed chair in wetland and waterfowl conservation and an associate professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Saskatchewan. Kevin Kraai is waterfowl program leader with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Dr. Mike Brasher is DU’s senior waterfowl scientist, based at DU national headquarters in Memphis.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy