Hail to the King

The regal canvasback occupies a special place in the hearts of many waterfowlers, but ongoing drought and habitat loss mean King Can is facing an uncertain future

The regal canvasback occupies a special place in the hearts of many waterfowlers, but ongoing drought and habitat loss mean King Can is facing an uncertain future

By T. Edward Nickens

We borrowed a canoe and tied it to the top of the car. And by "top of the car," I mean just that. We placed the canoe upside down on the roof of my ratty two-door Capri and lashed it down with ropes that passed through the open windows. It made for a chilly ride to the lake, but we were college kids at the time, and equal measures of crazy and tough. We paddled to a wooded point that knuckled into the lake, set decoys, and settled down. At that point in my life, I had hunted ducks maybe three times, so I didn't fully appreciate it when a single canvasback drake ripped around the point, in range.

I dropped the bird with my first shot. When I paddled out and pulled it from the water, I was more excited about the band on its leg than its species. But my pal, Jake Parrott, had more duck-chasing experience than I did, and he knew how special the moment was. When I recently talked to Jake about that hunt, we both tried to remember details of the day. It was nearly 40 years ago. "What I remember most," he said, "was how amazed I was that you and I could actually go down there by ourselves with our crappy gear, not knowing hardly anything, and manage to bag a king."

The canvasback has been known as the King of Ducks for who knows how long, and those of us who have pursued this wild, singular creature understand why it is so special. Part of it, for me, is because seeing canvasbacks is a rarity where I live, although there is a long historic connection to canvasbacks along the coastal sounds of my native North Carolina. Part of it is because the bird itself has such a stately air, with that blocky head and sloping brow, so regal in profile that it doesn't even need a crown to suggest a certain sort of royalty. Part of it is the canvasback's history, deeply woven in the fabric of waterfowling lore, science, and conservation. And part of it is the fact that the canvasback, pardon the unscientific verbiage, is simply such a cool duck.

Photo © Collection of C. John Sullivan

In 1986-just two years after I harvested my first canvasback-the hunting season for these regal birds was closed in the Atlantic, Mississippi, and Central Flyways, and the birds would be off-limits for years. I mounted my can, which had been banded in Saskatchewan, and I've displayed it on one wall or another in five different homes over almost four decades. It's a bit tattered and ratty today, but it still hangs near my office desk. I pass it a half-dozen times a day, and as it fixes me with that lordly red eye, I confess a temptation, still, to genuflect in front of the King.

The canvasback's nickname might be among the most memorable in the waterfowling world, but its scientific name and common English moniker have a few stories to tell as well. I've come across references theorizing that the canvasback got its name because prodigious numbers of the birds were toted to market in canvas sacks. Others hold that the textured pattern of its white wings resembled sails. The bird's scientific name, Aythya valisineria, is more straightforward to parse: The ornithologist Alexander Wilson first described the canvasback based on its love for Vallisneria americana, a.k.a. wild celery.

It was that staple of its migratory diet that helped affix the canvasback in the upper tiers of waterfowling lore. By choosing that savory submerged food, canvasbacks became some of the most highly prized of the market ducks. They fed heavily on the wild celery that once blanketed much of Chesapeake Bay, North Carolina's Currituck Sound, and other Atlantic Flyway waters. Situated close to major cities, which were knitted to the coast by quickly evolving transportation networks, those regions supplied canvasbacks and other ducks to the fish and game markets of New York, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, and other large cities.

In 1884, gunners on Church Island in Currituck Sound were paid cash on the spot by game buyers: one dollar for a pair of canvasbacks, 50 cents for a pair of redheads, and 25 cents for a foursome of teal, buffleheads, or ruddy ducks. A man had to work hard to make a living at those prices, but many did. According to Harry Walsh in The Outlaw Gunner, a Susquehanna Flats market hunter named Joseph Dye once took 76 canvasbacks with a single shot from a punt gun. Another local hunter topped that shot by killing 86 birds with a single trigger pull. On another morning, a pair of brothers gunning from sink boxes killed 350 canvasbacks and redheads. According to the legendary Forest and Stream editor George Bird Grinnell, 15,000 canvasbacks were shot each day during their wintering flights on Chesapeake Bay in the 1870s.

The birds were revered on the table. In The Golden Age of Waterfowling, Memphis writer Wayne Capooth described his city's opulent Luehrmann Hotel, whose restaurant was famed for its canvasbacks imported from Michigan. Three years after the blockbuster publication of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Mark Twain was on a long European tour and tired of the continent's food. He published a wish list of American food in his book A Tramp Abroad. "Canvas-back-duck from Baltimore" appeared on the list, just after woodcock.

Photo © Ken Archer

The canvasback's good graces on the table also had a darker side. Market hunting was beginning to decimate populations. In 1894, when a New York fish and game dealer was asked by The New York Times about which of his products were imperiled by the commercial trade, he replied: "Canvas-back ducks, red-head ducks, and the better kinds of game. All are increasing in price and decreasing in quantity. How will it all end? The buffalo was exterminated. Why not the oyster and the terrapin and the canvas-back duck and the other things that are worth living for?"

We can be thankful that King Can was not exterminated, although its population numbers have been on the ropes a time or two. Market hunting fixed the canvasback firmly in the imagination of waterfowlers, and it also helped to spur the country toward a greater embrace of conservation and waterfowl science. That's a pursuit that Ducks Unlimited biologists have been involved in with all the passion you could find among canvasback hunters on storied waters from Pool 9 on the upper Mississippi River to Lake Okeechobee.

Dr. Michael G. Anderson is emeritus scientist of DU Canada's Institute for Wetland and Waterfowl Research. Known as "Dr. Canvasback," he has studied the birds for half a century, much of that time in the famed pothole country near Minnedosa, Manitoba. He returns to the area each year to continue his surveys.

"The birds are beautiful and distinctive. They do a number of things differently than many other ducks in how they feed and nest and the journeys they make," Anderson says. On its breeding grounds, King Can lives a far less royal lifestyle than one might imagine. The birds use both large and small wetlands on the prairies, where hens build floating nests along the margins of the water and cattails. "One of the weird things about ducks is that they won't swim with nesting materials," Anderson notes. "That means canvasbacks need fairly thick cover to start with, and cattails or bulrushes can provide that structure. And their penchant for nesting in small potholes amazes people. I'll point out a little tenth-of-an-acre cattail pond with just a few square yards of water in it, and there will be a canvasback nest. People who only know these ducks from the winter, on really big waters, can hardly believe it."

But the ducks' narrow range of both breeding and wintering habitats effectively limits the species to a small population. During the severe prairie drought of the mid-1980s, the continental population fell to fewer than 400,000 birds but bounced back to healthy levels a decade later, when wet weather returned to the pothole country. Canvasback numbers peaked in 2007 with a population of 865,000 birds, the largest estimate since surveys began in 1955.

Photo © Todd J. Steele

Given the drought conditions that nesting birds faced on the prairies last spring, scientists are looking for another dip in canvasback numbers. "The birds like to nest in the margins where the water reaches vegetation, and during this drought the water might not have been in the margins," says Dr. Tom Moorman, retired chief scientist for DU. "Nesting success was likely very low." The good news is that canvasbacks are long-lived ducks, and in dry years they'll look for a safe place to spend the summer and molt, then return the next year and try again.

Ensuring that canvasbacks have a place to raise new generations is a race against the clock. In the canvasback's core breeding range of Saskatchewan and Manitoba, the bird faces significant challenges. In some key regions, provincial and local governments actually have programs to help facilitate wetland drainage, says Dr. Scott Stephens, DU Canada's director of regional operations for the prairies and Boreal Forest. "That's a struggle," he admits, "but that also means there is progress to be made to get policies in place that protect wetlands and recognize their broad benefits."

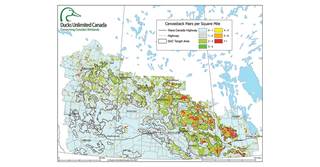

While work to change those policies moves forward, DU and its partners use a number of tools to conserve key habitats for canvasbacks and other waterfowl. By analyzing what are called "thunderstorm maps," which display duck breeding densities on the prairies, biologists can identify areas of particular importance to canvasbacks. "The maps look like the radar image of a thunderstorm rolling across the landscape," Stephens explains. "Like areas of heavy rain and lightning on a weather radar, areas where we know there are high densities of breeding canvasbacks will light up on the map." Once identified, those areas can be targeted for protection with perpetual conservation easements or acquisition through DU's Revolving Lands Program.

Some drained wetlands in prime canvasback breeding areas respond well to a relatively simple restoration technique. Many of these potholes were drained with a surface ditch, so plugging the ditch can be all it takes to restart the wetland's hydrological cycle. Since most wetland plant seeds have evolved to survive years of drought, the seed bank remains viable. "You can take a wetland that has been drained for 30 years," Stephens says, "and when you fix the hydrology, all those plants come back. It might take only a year or two, and it's very powerful to see that healing process."

Advancing technology could make it possible for producers of canola, wheat, and other crops to conserve wetlands on working agricultural lands in innovative ways. The data provided by precision agriculture, in which information technology helps producers make informed decisions about the most efficient use of resources, could also offer conservationists a significant new tool to help farmers reduce crop losses while boosting wetland acres on marginal lands.

Another wrinkle in canvasback conservation is the impact of nest parasitism on the productivity of breeding birds. Redhead hens frequently lay several of their own eggs in canvasback nests. It's an unusual reproductive strategy-goldeneyes and wood ducks occasionally do the same thing, but not as frequently as redheads.

When parasitism does occur, the canvasback usually gets the short end of the stick. The number of canvasback eggs in a clutch might be reduced by half. A canvasback hen often might hatch a brood of two or three redheads and only four or five of her own eggs. And since the incubation period for redheads is a few days shorter than it is for canvasbacks, redhead ducklings often hatch a bit earlier and get a leg-or a couple of wings-up on their nest mates. "They're among the first ducklings to get dried off and ready to go," Anderson explains.

For now, canvasback numbers may be lower than in the past few years, but fans should take (cautious) heart, because the rise and fall of duck populations is normal and expected. "Duck populations are boom and bust," Moorman explains. "They always have been, especially on the prairies. Canvasbacks can weather the current drought as long as it doesn't last like the decade-long drought of the 1930s." In one particularly dramatic turnaround, canvasback nesting success in southwest Manitoba during the drought year of 1977 was estimated at zero percent. Water returned the next year, and nesting success exceeded 70 percent.

I'd love to think that descendants of my Saskatchewan-born canvasback on the wall still occasionally find their way to the inland North Carolina waters where I first met the King. Flights of canvasbacks winging overhead are a majestic sight. So, too, is the spectacle of the birds strafing decoys in a North Dakota pothole, the cold air shrieking through their feathers. I've seen all that, and I hope to see it again. But I won't ever forget the sight of that single bird, cutting around the corner in the infant days of my waterfowling career-a wild, electrifying fragment of the northern prairies flung across the continent and straight into my decoys.

Ancienne noblesse. Such ancient royalty, indeed.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy