Knapp’s Island

A duck hunter travels to the spiritual home of Ducks Unlimited and uncovers the story of a man who cared as deeply about a small rural community as he did about North America’s waterfowl

A duck hunter travels to the spiritual home of Ducks Unlimited and uncovers the story of a man who cared as deeply about a small rural community as he did about North America’s waterfowl

By T. Edward Nickens

Photos by Peter Frank Edwards

Its the end of a long day of not much. Theres no way to sugar-coat it. Its mid-November and 78 sunny degrees on North Carolinas Currituck Sound. Theres not enough wind to snuff a candle, and its been this way since dawn, which was a long time ago.

Three days earlier, Ron Wade Jr. tells me, the ducks were everywhere. Ive hunted with Wade long enough to know hes a straight shooter. Three days from now, hell send me photos of his hunters tailgate mounded with ducks, with the apologetic caption: Wish you were here. But for the moment, I look out over the backs of goose and duck decoys, over the water and marsh and sky, and then at the single bufflehead reposed on the shooting rail, and think, Next time.

Its the end-of-a-slow-hunt benediction every duck hunter can recite from memory. Next time. Next time well have a little bit of weather. Or a little bit of wind. Next time I bet it will be a little colder up north. Next time well get em.

The refrain takes on a different meaning on Currituck Sound, however. The very fact that there is hope for the next duck hunters dawn is rooted in the marsh around Wades blinds, what happened here, and what has happened across North America because of what happened here. At the close of shooting hours, we empty the shotguns and Wade pushes the boat toward the decoys. I look out over the Knotts Island marsh, where a trio of swans is silhouetted in the falling light. I might be disappointed for the days show of ducks, except for what this place means and for the movement it launched, thanks to a man named Joseph Palmer Knapp.

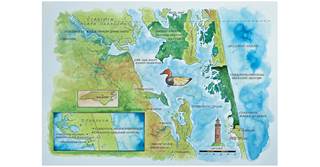

The marshes and woodlands around Knotts Island and Currituck Sound were a place of recreation and inspiration for Joseph Palmer Knappone of DUs founding fathers.

On this remote spit of marsh and pinewoods that juts like a bony knuckle into northeastern North Carolinas famed Currituck Sound, Knapp, a New York publisher, philanthropist, and son of a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company founder, hatched an idea and an organization based on what was then a pioneering concept: Instead of merely conserving wildlife through regulation, scientific principles of propagation and conservation could be used to actually increase game populations on the landscape.

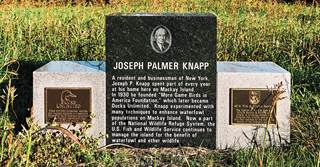

At Knapps palatial three-story, 37-room hunting estate on the southern tip of Knotts Island, he formed the More Game Birds in America Foundation. Incorporated on October 6, 1930, in the throes of the Great Depression, Knapps organization would take over management of Americas first school for gamekeepersthe Game Conservation Instituteand even pull off the first aerial international waterfowl population survey, the 1935 International Wild Duck Census. The group was eventually depleted by the economic woes of the period, and in 1936 More Game Birds in America shifted its resources and assets to a brand-new and even more visionary effort: the 1937 founding of a truly international organization called Ducks Unlimited.

Knapps estate on Live Oak Point was a cultural and economic anchor for the local community. He employed dozens of residents and provided funding to improve the areas schools and medical facilities.

Photo SPOONERCENTRAL.COM

So its true that the name Ducks Unlimited was born in a Beaverkill River fish camp in upstate New York, with its organizational structure codified in 1936 and its incorporation papers signed in the District of Columbia in 1937. But DUs spiritual birthplace has always been along the wild shores of the Knotts Island marsh. And there, nearly a century later, residents still recall the man who changed their islandand conservationforever.

Last November I spent two days on Knotts Island. I went to hunt, of course. Ive hunted with Wade over the course of a decade or better, and I can nearly guarantee that he wants his clients to shoot ducks even more than they want to. But I also went to find out just what remains of the Joseph Knapp legacy on the marshy peninsula.

Knapp passed away in 1951 at the age of 86. Shortly after his death, his Knotts Island property was sold and its timber harvested. Knapps former estate fell into disrepair and became a victim of vandalism. In 1961 the US Fish and Wildlife Service acquired 7,800 acres on the island, including the Knapp mansion, to provide habitat for waterfowl, and the decaying home was eventually removed. I wondered if any remnants of the house might be left, and what memories might remain from residents who can recall a time when this remote peninsula hosted throngs of wealthy hunters from the North.

Photo SPOONERCENTRAL.COM

Today, most of Knotts Island is part of the 9,500-acre Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge, but a strong guiding tradition continues, and a surprising number of residents remember the days when Knapp and his wife lived on the island for months at a time. Knapp used his fortune not only in support of conservation, but to shore up education in the remote communities bordering Currituck Sound. He built a school on Knotts Island that opened in 1926. He built housing for teachers, bought school buses, brought in medical staff to treat patients in Currituck County, and in 1947 donated a quarter of a million dollars for a statewide school needs assessment and a fisheries research program.

Photo Mike Reagan

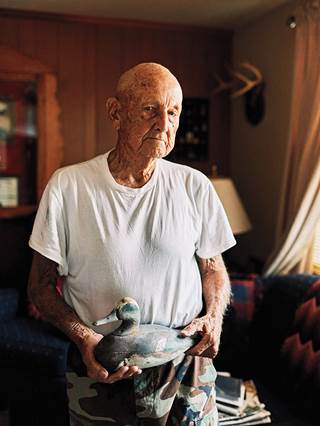

On the island, Knapp is less known for his estate than for his generosity. Anybody who wanted a job, he would hire them and pay double the money they were getting from the Works Progress Administration, recalls Joe Lewark, a longtime Knotts Island hunting guide and former caretaker of the old Swan Island Club and Currituck Sound Club. The Works Progress Administration was the federal program born during the Great Depression to employ workers to build roads, public buildings, and other large projects. Knapps massive mansion was an anchor for the island, employing dozens of residents as guides, groundskeepers, cooks, and more.

Local waterfowl guide Ron Wade Jr. grew up listening to his grandmother and great-grandmother tell stories about Knapp, the estate, and visitors from the North.

It was almost mythic how generous he was, Morris Waterman told me. Waterman was born on Knotts Island in 1931, attended classes in the schoolhouse Knapp built, and constructed his own home using foot-wide cypress weatherboards that came from a maids quarters that had been torn down on the Knapp estate. Like many on the island, Waterman remembers the Christmas gifts the Knapps handed out to Knotts Island childrenshoes and shirts, candy, and Christmas stockings. He recalls the opulence that surrounded the Knapps. Watermans uncle was caretaker of the Knapp estate, and Watermans father helped build the mansions signature curving staircase.

For Wade, memories of Knapp are relegated to the stories his mother and grandmother told. One afternoon we motor through Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge to a stake blindwhat locals call a bush blindthat Wade and his father built 60 years ago. Blind sites are carefully regulated on Currituck Sound. You have to re-up your blind every year, Wade says. And if you forget, thats it. You cant put a new blind anywhere in the county.

Morris Waterman attended school on Knotts Island that was built by Knapp.

Wades grandmother and his great-grandmother loved to play the piano, and they played it well. The Knapps would send a car to pick up Wades grandmother and bring her to the mansion to play. And that was back when there werent many cars on Knotts Island, Wade says, so it made quite a fuss. When Mrs. Knapp came to Currituck from New York, she would bring excess material and finery left over from the seamstresses who custom-made her clothing. She gave these luxuries to Wades great-grandmother, who made dresses for Wades grandmother. Wade laughs when he thinks of the irony. My grandma always said that, for being so poor, she was the best-dressed kid in Currituck County.

One of the most intriguing conversations I had on Knotts Island was with a feisty 83-year-old native named Jane Brumley. Brumley was born and raised on Knotts Island, where her father, Jim Miller, was a guide. I grew up with hunters and hunting, she says proudly. People will ask me, Why dont you have a Southern accent? And I tell them its probably because I was around all these Yankees all the time.

Jane Brumley holds a photo of the 37-room mansion, one of many in her collection.

Brumleys father loved history, and he passed on that passion to his daughter. The two of them used to explore local cemeteries together. Brumleys aunt and uncle worked for the Knapps, as did her grandfather, who would take her to the estate on Saturday mornings and let her roam the house and grounds. When the Knapps werent there, I had full range of the house, she says. She remembers the curving stairs that Morris Watermans father helped build, and the hidden liquor cabinet that was a staple of Prohibition-era estates.

Brumley has four filing cabinets stuffed with historical documents and artifacts. She pulls out two in particular. One is a small iron duck given to her father many years ago. She recalls that early leaders of DU returned to Knotts Island not long after DU was chartered and handed out the small mementos to locals. As far as she knows, it is the only one in existence.

The other is a rare photograph of the Knapp mansion taken by Bayard Wootten, a pioneering female photographer whose career spanned the first half of the 20th century. Brumley has a large silver gelatin print of the photograph, which shows gardens and sky and the faade of the soaring Knapp mansion, and she remembers it allthe saltwater pool, the ornate shrubbery, the Swedish maids the Knapps brought from their home in New York.

When I ask Brumley if shed let me borrow the print for a day, she briefly hesitates.

Ill bring it back tomorrow, I say. I promise.

I have a wild idea.

After the next mornings hunt, I meet Mike Hoff at the entrance gate to Mackay Island National Wildlife Refuge. Hoff is the refuge manager. He is proud of the progress the refuge has made through prescribed burns in the marsh and uplands, and of the sustainable smart shorelines planned to stem erosion and help clean Currituck Sounds waters. We ride to a marshy spit called Live Oak Point, passing a field of winter wheat planted for snow geese, where Knapps nine-hole golf course once stood. Theres a stone marker, erected by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, commemorating Knapp and his storied mansion, and a small, weathered kiosk outlining Knapps life. It seems somewhat forlorn and inconsequential, given what occurred here. I ask Hoff if many people show up looking for the homesite of DUs founder. Id expect a steady trickle, if not a stream, of waterfowlers on such a historic pilgrimage. But the refuge is far off the beaten path. No, he says, shaking his head. Very few. People are actually surprised when they hear of it.

When I pull out Bayard Woottens photograph of the Knapp mansion, Hoff studies it closely. I think that photo was taken from around the pool, he says. And I know exactly where that isI hit the foundation with a tractor one day.

I follow Hoffs tan-and-brown uniform as we edge through tall brush just a few feet from the seawall that has long protected this stretch of the shoreline. Hoff hesitates for a moment, then plunges into a soaring labyrinth of wisteria, privet, and who-knows-how-many species of briar. Im hot on his heels when we spot a tangle of tall phragmites up ahead. That stuff likes its feet wet, Hoff calls over his shoulder. Id say its growing inside of the old pool.

I hold back as Hoff shoulders through a wall of bramble and shrubs. A tangle under a giant water oak, its bark elephantine, its trunk arthritic and swarmed with vines, stymies us for a moment, and then we suddenly realize were standing on somewhat of a mound. I spot a deer trail tunneling into the thicket and follow it, stooping to worm through the brambles, but soon Im on my hands and knees, using my hat brim to turn away the thorns. When a cream-colored patch in the leaves catches my eye, I look closer. A piece of timeworn concrete emerges from the roots and muck. I brush away a few decades worth of rotting leaves, and the edge of Knapps concrete swimming pool emerges in the gloom.

Ive hunted the marshes of Knotts Island a half dozen times, and always my eyes were drawn to this tangled shore. It seemed hard to believe that such a historic site as Knapps mansion could molder away. It was always an odd reverie for a duck hunt: With ducks and geese and swans in the air, I often thought of what might be hidden away on shore.

Now I stand in a small opening in the brush, and I hold out Brumleys photograph. In it, a young, spindly pine tree anchors the center of the frame, with the curved roofline of the mansion just to the side. Standing on the edge of the old pool, I line up the photograph with a soaring old pine that clears the brush and thicket, its canopy framed in blue skyan old soldier from long ago. I cant help but think that Im in the right place, a long time later.

The famed photographer Bayard Wootten took this photo of the sprawling estate. The buildings are gone now, but the conservation legacy of Joseph Knapp continues through DUs continental habitat work.

And this may be all thats left, I think. All the rest is gone now. Dilapidated, torn down, carted away, grown over, forgotten. The mansion is gone, the boathouse is gone, the decoys are gone, the curving staircase that was unlike anything ever seen on Knotts Islandgone.

But the marsh and the ducks and the geese and the hope for more on the way remain. That was Joseph Knapps desire and dream. Hope for more ducks on frosty mornings. Hope and, thankfully, the means and vision to make it so. More fitting than a monument or building, and more enduring even than the memories of Knotts Islanders, his legacy is in every duck hunters sunrise.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy