Finding the Range

Take aim at trap, skeet, and sporting clays to fine-tune your waterfowl shooting skills during the off-season

Take aim at trap, skeet, and sporting clays to fine-tune your waterfowl shooting skills during the off-season

Author Phil Bourjaily is an avid clay target shooter and waterfowler.

No one is born knowing how to shoot. And you can’t become a better wingshooter simply by reading about it or watching a YouTube video. The best way to learn is by shooting clay targets on a trap, skeet, or sporting clays course. Even a half dozen trips to the gun club in the weeks before duck season will make a difference in your shooting. Here’s how you can bag more birds next waterfowl season by breaking clay targets this summer.

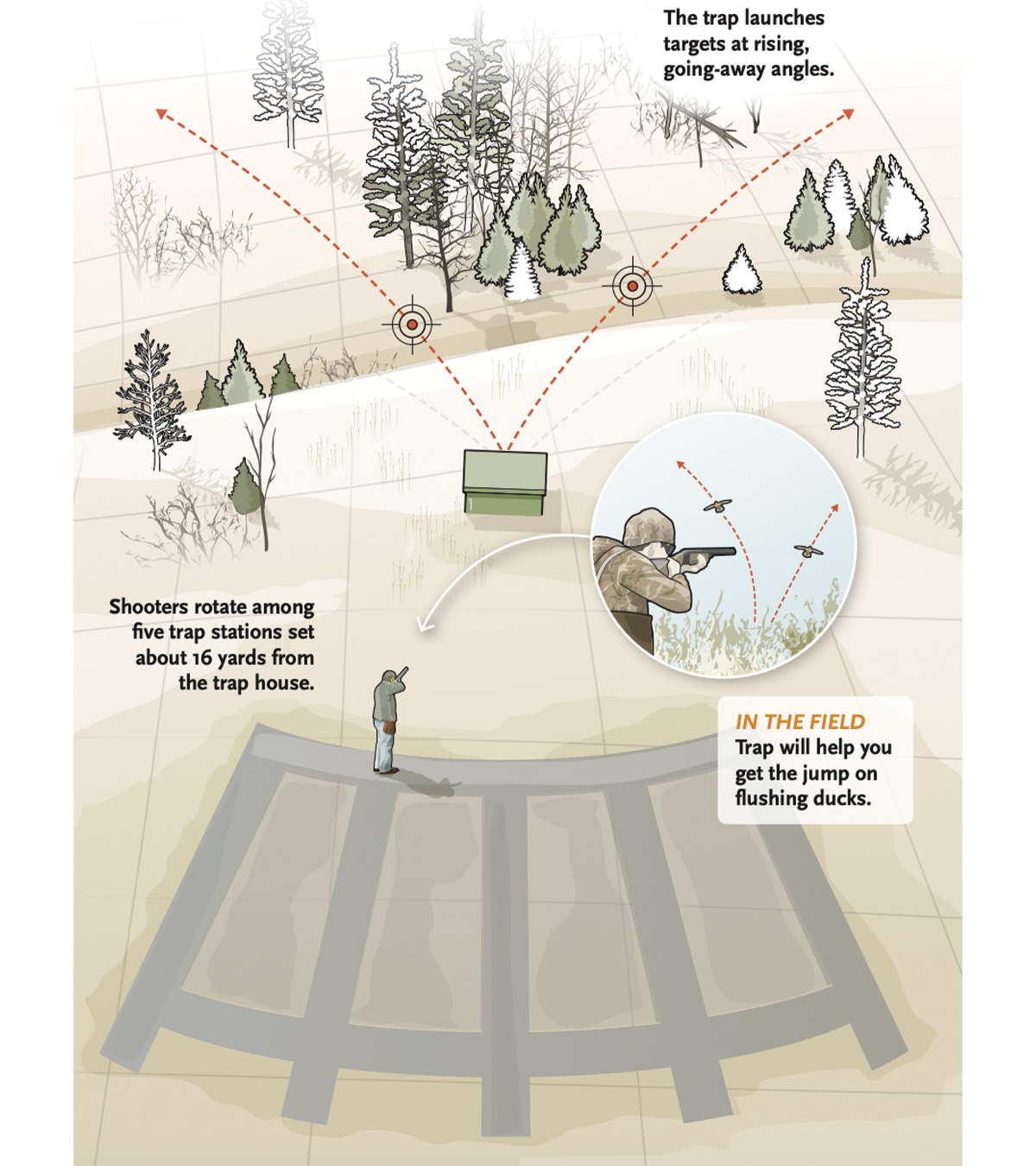

Trap is the oldest and most popular clay target game. Trapshooters rotate among five stations set up in an arc about 16 yards behind the trap house. The mechanical thrower—or trap—inside the house oscillates, launching targets at various angles from the shooter. For handicap trap, shooters stand between 17 and 27 yards behind the house. And in double trap, the machine doesn’t oscillate but throws two targets instead of one.

Most likely you’ll start out shooting 16-yard singles. In that case, load one shell at a time. You can have a live shell in your gun with the action open as you wait your turn. Remain at your station until the trapper or scorekeeper reads your score, then move to the next stand, keeping your gun open and unloaded.

Trapshooters have a reputation for being somewhat standoffish toward newcomers. There’s a bit of truth to that, because the actions of others in the squad can affect everyone’s shooting rhythm, concentration, and score. Just be ready when it’s your turn to shoot and remain quiet until it’s time to say “pull,” and you’ll be fine.

You will, however, need to control your empty shells. If you shoot an autoloader, you’ll absolutely need a shell catcher or a rubber band around the receiver to keep your empties from hitting the person to your right.

Guns and Loads

Shots at trap targets are long, around 35 or 40 yards. Using your duck gun with a modified, improved-modified, or full choke and an ounce or 1 1/8 ounces of size 7 1/2 or 8 shot will break any trap target. Be sure to bring 25 shells, plus a few extras. You’ll also need a bag or pouch to carry your live and empty shells. A hunting vest or a nail apron will work in a pinch.

Trap Tips

Consistency rules in trap. Your routine before the shot, as well as where you hold the gun and where you look for the target, need to be the same every time at a given station. For example, most shooters will hold on or above the left corner of the trap house when they stand at station 1.

This isn’t hunting, so don’t rush to load and shoot. Close your gun and mount it on the hold point. Then get your eyes up off the gun and look into the distance above the trap house. Think a positive thought, and call for the bird. The whole sequence takes about three seconds.

Never try to guess where the bird is going. Instead, see the bird first, read its angle, and then move the gun to it. Surprisingly, that makes the target seem to move slower—not faster—than if you try to aim down the barrel and chase the blur of the target out of the trap house.

Shoot just before or as the target peaks. Waiting too long, as many new trapshooters do, means you’re shooting at a dropping target that’s slowing its rotations, making it harder to break. It probably means you’re aiming, too, and trying to double-check to make sure you’re on the target. Trust your eyes and hands—and shoot.

What You’ll Learn

With its shallow, going-away angles, trap resembles jump-shooting more than it does any other kind of waterfowling. If you stalk ducks in sloughs, this is the game for you.

Trap also teaches fundamentals, including one a lot of waterfowlers have trouble with: keeping your head on the gun. Heavy duck and goose loads generate a lot of recoil, and many hunters develop a subconscious lift of the head to get up off the stock and away from recoil. Trap shooting punishes head-lifting mercilessly, causing misses over the top. You’ll quickly learn not only how to diagnose the miss but also how to correct it by keeping your head on the gun all the way through the shot—because if you do stick your head up to watch the target break, you’ll surely miss.

Skeet was invented as hunting practice by two grouse hunters in the 1920s. There are two trap houses, a high and a low house, and eight stations on a skeet field. The first seven stations are aligned in a semicircle from the high house to the low house, and the last station is in the center of the skeet field, midway between stations 1 and 7. Skeet targets fly at the same height and angle every time, passing over a crossing stake set 21 yards from the stations.

In a round of skeet, shooters get 25 shots apiece. Stations 1, 2, 6, and 7 feature a pair of single shots—one from each house—followed by a double. The other four stations offer only a single target from each house. Shooters get an immediate repeat shot (called an option) at the first target missed.

Skeet is a more sociable game than trap, and conversation between shots is usually fine. If you shoot a break-action gun, cover the breech with your hand to catch empties, and stash them in a vest pocket or pouch. With pumps and autoloaders, let the empty cartridges fly and pick them up after the round is over.

Guns and Loads

Guns for skeet should have open chokes such as cylinder, skeet, or improved-cylinder. Serious competitors use size 9 shot to increase the probability of a hit, but 8s and 7 1/2s are also good target loads for this game. Competitive skeet is shot with everything from a 12-gauge to a .410-caliber shotgun, and all the targets are in range of small-bore guns.

Skeet Tips

In skeet, as in all clay shooting, finding the right hold point (where you start your gun) and look point (where you pick up the target with your eyes) makes the game easier. Although it’s tempting to call for the target with your gun pointing at one of the trap windows, try moving your muzzle several feet ahead, then cut your eyes back closer to the window so you can see the target sooner. When you set up that way, the target comes to the gun and seems to fly slower.

Skeet can be shot by swinging through targets from behind, which is how most of us learned to shoot, but that’s the hard way. If you hold your gun far enough off the house, you never have to let the target pass your muzzle. Using some form of maintained lead or pull-away works best. Be advised that skeet targets at stations 3, 4, and 5 require very long leads; after a summer of skeet shooting you might have to shorten your leads slightly in the field.

What You’ll Learn

Although it was invented for upland hunters, skeet actually offers more to waterfowlers. The clay bird on High House 1 is like a wood duck coming in from behind early in the morning. The incomers from Low 1 and High 7 are similar to diving ducks that don’t flare when they see you but speed up and keep coming. And the crossing shots at stations 3, 4, and 5 simulate ducks skirting the decoys.

In addition, the maintained-lead and pull-away methods that win on the skeet field work very well in the marsh too. Keeping your muzzle in front of real birds instead of trying to swing through them lets you move the gun slowly and under control instead of scrambling to catch a departing target.

Skeet competitors shoot with a premounted gun. But if you play the game the old-fashioned way and call for the target with a dismounted gun, you’ll be getting great gun-handling practice.

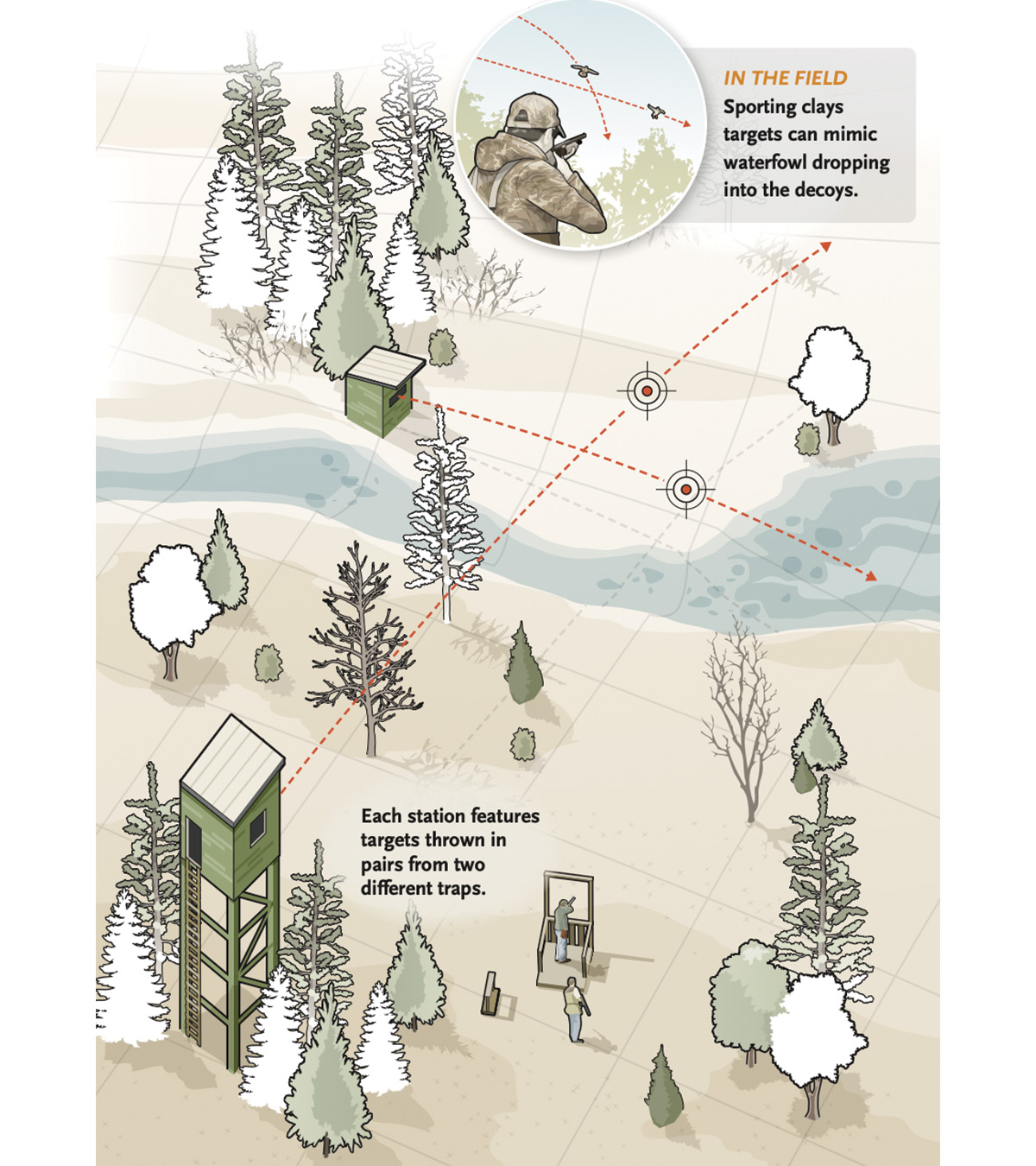

The game of sporting clays was imported in the 1980s from England, where it was called hunters clays because it duplicated field situations. It has since evolved into a game of its own, with targets that curl, bounce, fall, and shoot straight upward, as well as many that still mimic real birds.

A round of sporting clays consists of 50 or 100 targets, all thrown as pairs, and there are usually five pairs per station. No two sporting clays courses are the same, and every course changes periodically. Unlike trap and skeet, where perfect scores are common, sporting clays scores are much lower. Depending on the course, you should be happy to break more than 50 percent of the targets the first time out.

Paired targets come in three types: true pairs, in which both targets are launched simultaneously; following pairs, where one target is thrown shortly after the other; and report pairs, in which the second target is released on the report of your gun. There will be a sign at each station telling you what to expect. The shooting order rotates, so everyone takes a couple of turns as the guinea pig, going first at a new station.

The most sociable of the target games, sporting clays permits plenty of conversation, joking, and advice sharing as you make your way from station to station. You’ll need a bag to carry 100 shells and some extra ammo. A round of sporting clays will last at least an hour, so you might want to carry along a bottle of water as well. Some clubs rent out golf carts to transport you and your gear around the course, which can be spread out over several acres.

Do not load your gun until you have stepped into the shooting cage and your muzzle is pointing downrange. The first shooter gets to call for a “show bird” from each trap at a new station. You can look at the target and point a finger at it, but don’t point your gun unless you are in the shooting cage.

Guns and Loads

A 12- or 20-gauge duck gun with an improved-cylinder or light-modified choke is a good all-around choice for sporting clays. Although some shooters bring a variety of shells to accommodate different target distances, an ounce to 1 1/8 ounces of size 7 1/2 or 8 shot will cover all the bases. Choke changing is permitted before you shoot at each station, but once you start shooting, you must stick with what’s in the gun.

Sporting Clays Tips

Watch the show targets all the way to the ground to get a clear idea of how close or far away they are, and what they are doing in the air. Make a plan. For example, when shooting a true pair, decide which target you will break first and where you will break the targets. Sporting clays is like pool, in that you want to plan your first shot so it leaves you in a good position to shoot the second target.

Also determine where you will look for the birds and where you will start your gun. There’s a point in the flight of most birds at which they look big, fat, and easy to see. That’s the spot where you should plan to shoot it. Stick to your plan if it’s working, as you’ll have to execute it five times in a row to shoot the 10 birds. If your plan isn’t working—change it.

Whereas all the targets move at the same speed in trap and skeet, there are fast and slow birds in sporting clays. Pay attention to target speed and move your gun in time with the bird.

Start your muzzle where it won’t block your view of the target. For most birds, that means pointing below the line of flight, but it can also mean holding to one side of a bird like a springing teal, which goes straight up.

As with skeet shooting, you’ll have a hard time breaking long crossing targets if you try to swing through them from behind. Start your muzzle away from the trap and never let the target pass it. Stay in front of and below the clay bird.

What You’ll Learn

Sporting clays presents almost any waterfowling situation that you can imagine, from high overhead passing shots to long crossers to ducks dropping into the decoys and then flaring out of them. Unlike trap and skeet, however, sporting clays is harder to get grooved into because the targets are always changing. You need to learn to read the line of flight and put the gun in the right place, just as you do with unpredictable wild birds.

Because every station presents a double, you have to make the most out of both shots, a skill that serves you well when a flock of ducks or geese comes into the decoys. The fact that you can shoot without premounting the gun is another great advantage of sporting clays.

Some sporting clays stations have nothing to do with field shooting. If you’re there solely for preseason practice, go ahead and shoot only the stations that simulate the type of hunting you do. That’s the best way to find the range on the types of shots you’ll see come duck season.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy