High and Dry

Drought and other long-term water challenges threaten the heart of the Pacific Flyway

Drought and other long-term water challenges threaten the heart of the Pacific Flyway

by Mark Petrie,PhD, and Ryan Sabalow

William Finley was a director of the Audubon Society when he crossed the Cascade Mountains into the Klamath Basin in the summer of 1905. But that year he also carried a badge. Oregon had deputized the well-known naturalist and assigned him the task of ending the state’s feather trade. At the time, thousands of birds were being killed in the Klamath Basin for fashion, their feathers used to decorate hats and clothing. Although much of the basin was high desert, its unique geology formed three massive lakes—the Upper Klamath, the Lower Klamath, and the Tule. Together, they spanned 350,000 acres of seasonal and permanent marshes. When Finley saw them, they teemed with so many egrets, grebes, terns, and pelicans that he quickly declared the Klamath Basin the most important breeding grounds on the Pacific Coast. Knowing that he could never patrol such a vast wetland wilderness, he instead convinced the Oregon Milliners’ Association to stop purchasing the skins of local birds. In his words, “We cut at the roots instead of hacking off the branches.”

His mission fulfilled, Finley left the Klamath Basin before he could see the millions of ducks and geese that arrived each fall. His departure also coincided with the end of the region’s splendid isolation. By 1906, work had begun on the Klamath Basin irrigation project, which would eventually bring over 200,000 acres of land into production. Both Tule Lake and Lower Klamath Lake were mostly drained and converted to farmland, while Upper Klamath Lake was left as a source of irrigation water.

Finley knew these places would soon be gone. Today, we can be thankful that he was not without friends. In 1908, he petitioned President Theodore Roosevelt to protect what was left of these incredible wetland landscapes. Roosevelt responded with an executive order that established the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge, making it the nation’s first refuge for migratory waterbirds. Twenty years later, nearby Tule Lake also became a national wildlife refuge.

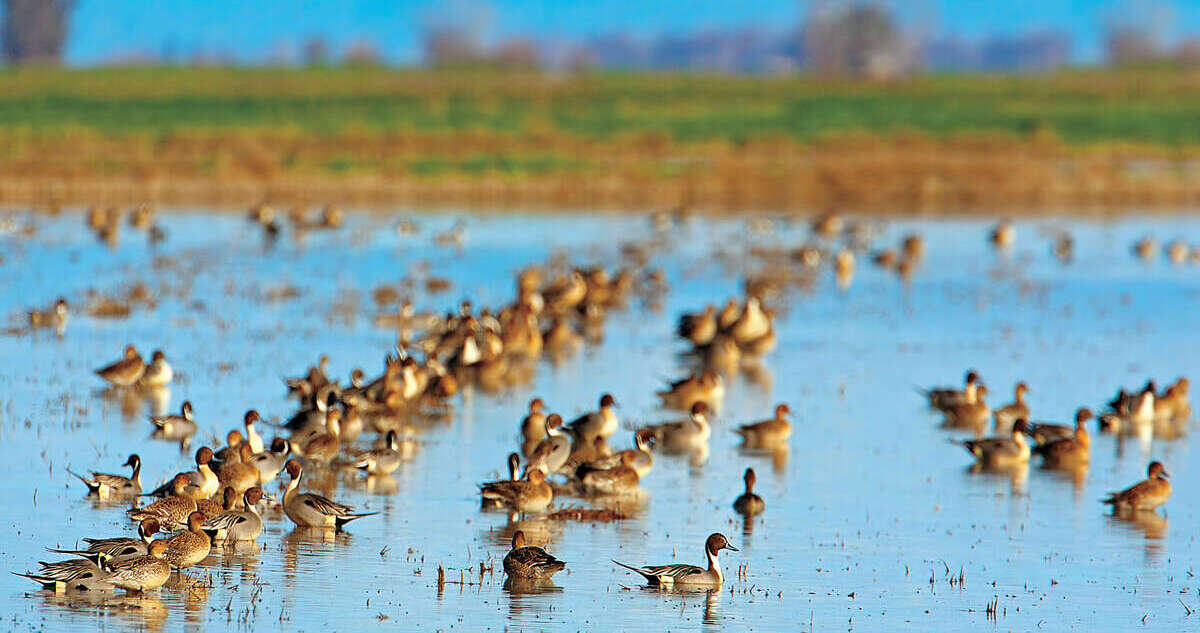

It is no small irony that the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges were created in the midst of an irrigation project dedicated to their drainage. The refuges and agricultural interests eventually reached a truce, and over time were able to prosper side by side. By the 1950s, the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges had become some of the most important public habitats for migrating waterfowl in the United States. They held staggering numbers of waterfowl. In 1957, more than 3 million northern pintails were counted on Tule Lake alone.

By 2022, both refuges were completely dry, and the massive rafts of waterbirds that used the area during Finley’s time were long gone. The recent western drought is just part of the reason. Over the past 20 years, regulators have gradually sent Klamath Basin farms and refuges less water in order to meet the needs of endangered fish populations in Upper Klamath Lake and the Klamath River.

Despite their importance, the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges are a geographic rounding error within the landmass of the Pacific Flyway. Why be concerned about two dots on a very large map? The answer lies in the very nature of the West. Waterfowl and other wetland-dependent birds disproportionately rely on the West’s few low-lying areas that historically provided large areas of wetlands. As a result, most birds are concentrated in just a handful of places. In fact, just three areas support 70 percent of all waterfowl in the Pacific Flyway from fall through spring—what we call the Big Three. These include the Central Valley of California, the Great Salt Lake, and the border region of Southern Oregon and Northeastern California, called SONEC for short. At the heart of the SONEC region lies the Klamath Basin.

The Big Three share the same populations of waterfowl and other wetland-dependent birds. In the fall, birds migrate through the Klamath Basin and the Great Salt Lake and then into the Central Valley. In spring, they retrace their flight on their way back to their breeding grounds. Unfortunately, the Klamath Basin is not alone in its woes. The Great Salt Lake is now at its lowest level since records were first kept in 1847. Nearly 70 percent of the lake’s 500,000 acres of wetlands are dry, and only managed wetlands fed by canals and shaped by levees currently hold water. Until the storms of January 2023, the Central Valley was hardly in better shape. Rice provides half of all the food available to waterfowl in the valley, but last May a lack of water led to less than half the rice ground being planted. To make matters worse, only about 50 percent of all wetlands in the Central Valley had been flooded by late November 2022. As was the case in the Klamath, the shortage was caused by a combination of drought and the fact that water for farms and wetlands was being held back for endangered fish.

It’s been said that the West was “built on an empire of snow,” and there is no doubt that habitat conditions in the Klamath Basin, Great Salt Lake, and Central Valley are closely tied to annual snowpack. Snowmelt feeds the West’s rivers and reservoirs, and from there its wetlands and waterfowl-friendly crops. Yet annual snowpacks are now providing less runoff than they once did because of higher temperatures and increased evaporation, while the West’s demand for water has only increased.

Irrigated rice fields are among the most important habitats for waterfowl and other wetland birds in California’s Central Valley.

The West has two types of wetlands: managed and unmanaged. Managed wetlands contain water-control structures and levees that allow water levels to be manipulated throughout the year. Unmanaged or natural wetlands lack such infrastructure. Most managed wetlands in the Big Three rely on annual deliveries of surface water, and without these water diversions they will go dry. The same is true for working lands important to waterfowl and other wetland-dependent birds. More than 80 percent of all the food available to ducks in the Big Three is provided by managed wetlands or by waterfowl-friendly agriculture like rice. Yet these habitats exist only if we divert water in their direction. This is a dangerous and growing vulnerability on landscapes where surface water supplies are increasingly scarce as snowpacks shrink and the demand for water grows.

Many unmanaged wetlands are even more at the mercy of annual snowmelt and a changing climate than managed wetlands. A recent study by Patrick Donnelly of the Intermountain West Joint Venture revealed that many of these habitats are getting drier. Donnelly found that the length of time that wetlands hold water in the West has declined over the past 40 years. These declines have disproportionately impacted semipermanent wetlands, which typically remain flooded throughout the year. Donnelly states that “in the last decade, semipermanent wetlands have declined by over 40 percent in places like SONEC. These drying wetlands are transitioning to shorter flooding regimes that are helping to backfill losses of many seasonal or temporarily flooded wetlands that are now often dry altogether, but there is nothing to replace semipermanent wetlands. The urgency to overcome these conservation challenges will only grow as temperatures continue to warm.”

What can be done? First and foremost, we need to make sure that the managed wetlands and waterfowl-friendly agriculture that now feed most of the waterfowl in the Pacific Flyway get enough water. But doing that will require broad support for the work that DU does. Water users across the West would benefit from the recovery of endangered fish, and DU’s work needs to be viewed in that light for those outside the organization’s traditional circle of support. Put another way: Water for wetlands and farms will only become reliable once fish populations stabilize and recover. Healthy, viable wetlands will be key to that recovery.

There is a growing awareness among fish biologists that flushing water down rivers or holding it back for fish will not be enough to bring them back from the brink of extinction. Endangered fish populations in the Klamath Basin and Central Valley rely on wetlands during crucial parts of their life cycles. Unfortunately, many of these wetlands are seriously degraded, are no longer accessible to fish, or have disappeared altogether. Nobody is better able to help restore those wetlands than Ducks Unlimited, which can do it in ways that meet the needs of birds, fish, and people.

Although the Great Salt Lake and its watershed are not home to endangered fish, this important area is also suffering from a lack of water, and nobody living on the Wasatch Front is spared the consequences. As the lake bed dries, it gives way to toxic dust storms. Many of the commercial industries that rely on the lake are also threatened by low lake levels. Even the famous Utah powder so cherished by skiers is at risk since much of the snow is produced by the Great Salt Lake’s remarkable “lake effect” weather patterns. A smaller lake will lead to less snow and fewer days on the mountain. That’s bad news for the region’s tourism-based economy.

Sixty percent of the water reaching the Great Salt Lake is delivered by the Bear River. But as demands on the river increase and snowpacks decline, less water is reaching the lake. Joel Ferry is executive director of the Utah Department of Natural Resources, and he is helping to lead the charge to get more water back into the Bear River. “There are real opportunities to increase the efficiency of how agricultural water is used in the Bear River watershed and to increase river flows,” Ferry says, “and DU and others concerned about the Great Salt Lake have an important role to play.”

The ongoing drought and the long-term plight of the Big Three have done much to focus DU’s conservation efforts in the West. In November 2022, DU launched its Great Salt Lake Initiative at a ceremony with Utah Governor Spencer Cox and DU CEO Adam Putnam in attendance. The objectives of the initiative include improving the infrastructure of the lake’s managed wetlands, working with the agricultural community to increase water-use efficiency, and helping to control invasive plant species. Grants and donations totaling nearly $2 million have been secured from many individuals, foundations, and corporations, including Marathon Petroleum, Dominion Energy, and Procter & Gamble. DU’s philanthropic goal is to raise $5 million for this effort over the next five years. DU was also awarded a North American Wetlands Conservation Act grant to support the initiative. With this new funding dedicated to the Great Salt Lake, DU has added biological, engineering, and policy staff to help see these objectives through.

Similar work is under way in the Klamath Basin and Central Valley. In 2021, DU announced its Klamath Basin Initiative, an effort aimed at finding water solutions that work for refuge, agricultural, and tribal interests. Key to DU’s effort: the role of wetlands in helping recover endangered fish. In the Central Valley, DU is working with agriculture and fish advocates to find solutions that meet the needs of farmers and fish, all while supporting millions of waterfowl and other migratory birds that gorge in rice fields that are flooded after harvest. To date, the Klamath Basin Initiative has secured over $1 million in commitments from concerned individuals and organizations, including a generous grant from the Harvey L. and Maud C. Sorensen Foundation.

“Whiskey is for drinking and water is for fighting” goes the tired but prophetic phrase. But in those parts of the West that are crucial for waterfowl and other wetland-dependent species, DU can help avoid those battles and seek solutions that work for everyone, all while creating healthy populations of fish and birds. That’s a goal that early conservation leaders such as William Finley and Teddy Roosevelt surely would have rallied behind a century ago.

We owe it to their legacy—and to our birds and fish—to find a better way.

With support from Procter & Gamble (P&G), Ducks Unlimited will improve water quantity and quality in the Lower Bear River and Great Salt Lake watershed by enhancing 625 acres of wetland habitat and increasing irrigation efficiency on 230 acres of farmland. DU will convert over 5,000 feet of earthen ditch to pipe to improve irrigation efficiency and provide supplemental water to wetlands on two sites in Utah’s Box Elder County. By improving water management, these projects will allow better control of invasive species that can crowd out native plants and degrade waterbird habitat.

P&G has announced a strategy to help build a water-positive future by reducing water use in manufacturing, responding to water challenges through innovation and partnerships, and restoring water for people and nature. As part of that announcement, P&G is partnering with the Bonneville Environmental Foundation’s Business for Water Stewardship to help fund these DU projects and several others in the western United States. Learn more at us.pg.com/mapping-our-impact/.

Dr. Mark Petrie is director of conservation planning and Ryan Sabalow is communications coordinator in DU’s Western Region.

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy