Marsh Terraces as a Conservation Practice

Louisiana has the highest rate of coastal wetland or marsh loss in North America. Currently, Louisiana loses 25 to 35 square miles, or 16,000 to 22,000 acres, annually, which equates to losing an area the size of football field every 30 minutes. Nearly 1,500 square miles of marsh have been lost over the past seven decades. The causes of marsh loss in Louisiana are complex, but primarily are attributed to alterations of natural hydrology.

Main line levees on the Mississippi River prevent deltaic processes from building marsh in southeastern Louisiana, and they also have reduced the long-shore mud stream that builds marshes in the Chenier Plain of southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas. Further damaging these marshes, construction of navigation channels and oil exploration canals, particularly in the Chenier Plain, allow saltwater to intrude into areas of the marsh where vegetation is less tolerant of high salinity. Extended exposure to saltwater causes death of marsh vegetation, leaving large open areas of shallow muddy water void of submersed aquatic or emergent vegetation. Submerged aquatic plants and detritus are the basis of the food chain in the coastal marsh. Submerged aquatics directly provide vital food, while detritus supports invertebrate production, both of which sustain several million waterfowl each winter.

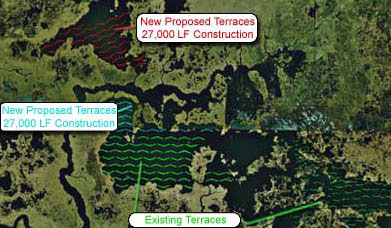

Where natural hydrology and marsh building processes cannot be re-established, or until such time as they are re-established, management of hydrology and salinity regimes to mimic historical patterns can restore some areas of deteriorating broken marsh. For example, installation of perimeter levees, water control structures, canal plugs, or some combination of these techniques, allow management of hydrology and salinity to mimic historical patterns, particularly in southwestern Louisiana and southeastern Texas. Upon establishment of perimeter protection that allows control of salinity levels, earthen terraces may be constructed (where soil types allow) to reduce the impact of wind and waves in areas of broken marsh in an effort to reduce rate of interior marsh loss by erosion. Further, by reducing wave action, water clarity appears to improve dramatically, allowing sunlight to reach the marsh bottom and stimulate growth of submerged aquatic vegetation. This often results in excellent habitat for waterfowl, alligators, and several commercially important marine species such as white and brown shrimp, red drum, and blue crabs, and for a host of other wetland-dependent wildlife and fish species.

The terraces are arranged in an alternating pattern at 30-degree angles and are approximately 1,000 feet long, 40 feet wide at the base, and about 10 feet wide at the top. The surface of each terrace is approximately two feet above water level and is planted with native vegetation to reduce erosion. They are typically designed in a "V" shape (we typically refer to this as a "duck wing terrace") so that regardless of the wind direction, calm water will exist on the downwind side of the terrace.

When Hurricane Rita struck southwestern Louisiana, marsh management infrastructure, especially perimeter protection of interior marsh, was damaged and will need to be repaired to protect these marshes from saltwater. However, the terraces constructed in interior marshes were not significantly impacted. In fact, the terraces appear to have had some unanticipated, potentially beneficial, effects. Hurricane Rita literally scoured and ripped up large areas of marsh. Some of this vegetation and its attached soil were captured by terraces and deposited in broken marsh areas. It is likely that the vegetation deposited in the terraced marshes by Rita is dead or will die, but it also seems probable that the soil and other organic debris may increase marsh elevations and allow establishment of emergent vegetation that will aid in the marsh building process in these broken marshes.

The following images provide a brief look at the potential benefits of marsh terraces on the coastal Louisiana landscape. Photo captions document their construction date, location and subsequent effects from hurricanes Katrina and Rita.

This photo was taken approximately 1 month after construction. You are looking south-west at terraces built on USFWS property. This project was part of a North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA) grant awarded to DU to build terraces on public and private land located within the Cameron Creole Watershed. These sites were evaluated and went through DU's terrace selection criteria. This photo is of newly constructed terraces planted with single row plugs of Spartina alterniflora oriented in the "duck-wing" pattern. |

This is a post Rita October 2005 image of terraces built through a NAWCA grant in 2002. This photo was taken looking north. It appears as though some marsh has settled on the south side and throughout the terraces that was uprooted from the storm. Unfortunately this marsh came from some other place but it was not lost to the Gulf of Mexico or adjacent lakes. While this vegetation may die back from stress the end result should be a gain in elevation around the terraces which should improve conditions for aquatics and possibly emergent vegetation. |

This image (looking southwest) is of terraces built in the spring of 2005 on private lands within the Cameron Creole Watershed. If you look at the left center of the photo you can see the island right next to the terrace as mentioned in the next photo. |

This photo is looking east on terraces that were constructed on private lands within the Cameron Creole Watershed in the spring of 2005. A landmark to note is the small island near the center of the photo. |

This is on private lands within the Cameron Creole Watershed. The terrace is on the top left of the image and you can see marsh and mud all around it. These terraces were built in 2002 in open water ranging from 1 to 2 feet. |

This photo is looking north at terraces constructed in 2002. All terraces were constructed in open water areas ranging from 1 to 2 foot in depth. What is shown here is what appears to be marsh that has settled mostly on the south side of the terrace. While it is hard to predict, there is a chance that the gain in elevation will result in emergent marsh and scattered ponds around some of the terraced areas. Unfortunately this is not new marsh and was uprooted from the surrounding area. |

This photo shows the gap left between terraces and what appears to be marsh scattered throughout the terraces. This is on private lands within the Cameron Creole Watershed and the terraces were built in 2002. |

Ducks Unlimited uses cookies to enhance your browsing experience, optimize site functionality, analyze traffic, and deliver personalized advertising through third parties. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. View Privacy Policy