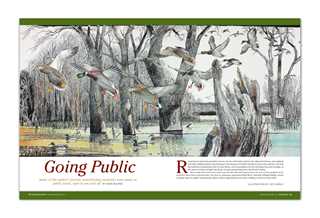

Going Public

Many of the author's favorite waterfowling memories were made on public lands, open to one and all

Many of the author's favorite waterfowling memories were made on public lands, open to one and all

.jpg)

From the Ducks Unlimited magazine Archives

By Wade Bourne

Recent heavy rains had caused the river to rise out of its banks and into the adjacent bottoms, and mallards and other dabbling ducks were flocking to the banquet of freshly flooded acorns in the oak flats.

My host had enjoyed a sensational hunt the day before, and our prospects for this morning were just as bright, as the arrival of dawn brought big flocks of ducks plummeting into the flooded timber.

What made this hunt extra sweet was the fact that this honey hole was not on the property of an exclusive duck club or private lease. We were on Arkansas's sprawling White River National Wildlife Refuge, which is largely open to public hunting and offers endless opportunities for those willing to work for their birds.

Public hunting areas are a cornerstone of our waterfowling tradition. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation was founded on the premise that wildlife belongs to everyone; therefore everyone should have access to these resources. Hunters have certainly paid their own way by funding the acquisition and management of public hunting areas through license and duck stamp sales, excise taxes on firearms and ammunition, donations to Ducks Unlimited and other conservation organizations, and much more.

In almost five decades of waterfowling, I have chased ducks and geese on national wildlife refuges, wildlife management areas, national and state forests, military reservations, private lands open to public hunting, and many other areas. Some of these places have provided me with the best duck and goose hunting imaginable. Following are just a few of my most memorable public waterfowl hunts.

"Number 4" was the place where I earned my stripes in duck hunting. Such was the designation given to the last field in the bottoms on a west Tennessee wildlife management area. This seasonally flooded area, managed by the Tennessee Game and Fish Commission (forerunner of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency), was one of those magic spots where ducks just wanted to go.

Phil Sumner and I were in our late teens, and we had fire in our bellies. It was no secret that Number 4 was a hotspot, and because it was open to all on a first-come, first-served basis, we made it a point to get there early. We'd arrive in the area's parking lot two hours before shooting time. After sliding Phil's johnboat out of his pickup bed, we'd load our gear, clamp on my old three-horse outboard, and start snaking through the timber toward Number 4.

What should have been about a 10-minute trip took us a good half-hour because my motor ran hot and would lock up after taking us only a few hundred yards. We would chug along until the outboard seized, paddle while it cooled off, and then crank it back up again. It took about three of these cycles to reach Number 4.

Permanent blinds weren't allowed on this management area, but someone had piled brush in a U shape on the point of a tree line where the ducks flew in from a nearby refuge. When we jammed our boat inside the U, we were fully concealed from circling birds' wary eyes.

We didn't bag limits there every day, but we were rarely skunked. And looking back, this spot provided good on-the-job training for setting decoys, calling, shooting, and other hunting skills. It never succeeded, however, in making us outboard mechanics.

Today, more than 40 years after my last hunt there, I look back on Number 4 with great nostalgia. In those youthful days I was crazy about duck hunting and girls, in that orderand Number 4 was my first true love. I couldn't get enough of her then, and she still holds a special place in my heart and memory today.

PLOTS is an acronym for Private Lands Open To Sportsmen, a program in which the North Dakota Game and Fish Department contracts with farmers to open their lands to public hunting. The department publishes an atlas showing the location of these tracts for hunters who wish to access them.

Bob Meek and I were on a muddy section road west of Devils Lake studying a PLOTS book. A freak early fall storm was raging, and the water was too rough to boat hunt on the lake, as we'd planned. So instead we were driving back roads looking for a sheltered marsh that we could hike into, toss out some decoys, and hide in adjacent cover. The book offered several possibilities.

The first couple of spots we checked showed little duck activity, but the third place looked promising. Steady flights of mallards were working into a harvested cornfield posted with "No Trespassing" signs.

But the ducks were coming from a tall grass pasture behind us that was marked with a welcoming yellow triangular PLOTS sign.

"Must be a pothole out in the middle of that field," Bob said, before climbing onto his truck's toolbox for a better look. As Bob raised his binoculars, a hawk flew over the middle of the field and a veritable curtain of ducks lifted into view. "There they are," he said, as the birds settled back down. "Looks like a good-sized marsh, and ducks are all over it."

We pulled on waders, shouldered bags of decoys, and started hiking toward the mother lode, which is exactly what it turned out to be. Puddle ducks of several species were flying low over the shallow water and cattails. We waded a few yards into the marsh and set our spread in an opening where several mallards had flushed. Then we hunkered down in a thick stand of cover to await the next flight.

We didn't have to wait long. The action was steady, and soon we had taken a mixed bag of mallards, gadwalls, pintails, and green-winged teal. The shooting was deceptive in the strong, steady wind. Most ducks were flying straight into the blow, which greatly slowed their progress. For once, we had to concentrate on not leading the ducks too much.

Several states have programs similar to PLOTS. South Dakota's Walk-In Areas and Kansas's Walk-In Hunting Access programs are two examples. These efforts provide public access to high-quality private lands, offering ample opportunities to hunters who have the gumption to seek them out.

Nobody warned me that I should reconsider standing up to shoot from a pirogue. Besides, my two hunting partners were doing it. The fact that they had grown up in these boats didn't deter me, but it should have.

We were on Delta National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) on the east side of the Mississippi River downstream from Venice, Louisiana. This 49,000-acre refuge is a mosaic of freshwater and brackish ponds and marsh.

Accessible only by boat, Delta NWR offers high-quality public hunting for those who can get there.

The September teal season was open. Devlin Roussel and Mike Ellis had invited me to join them on a traditional Delta teal hunt. We'd launched Devlin's large fishing boat before dawn at the Venice marina and headed downriver. After we'd run several miles, Devlin turned into Main Pass and motored a few more minutes before taking a winding, twisting trail into the marsh.

Finally he killed the big engine, dropped anchor, and unloaded three pirogues that we'd ferried in. Our plan was to paddle these traditional Cajun craft to a nearby pond where Devlin thought teal should be working.

I'd never been in a pirogue before, but I was aware of their reputation for being tippy. Devlin steadied my boat while I climbed in. Then he and Mike hopped into their own boats, and soon we were paddling farther into this chaos of water, weeds, smells, and marsh sounds.

I covered the 200 yards to our hunting site without a problem. The tide was low, and the water was calf deep where Devlin and Mike tossed out our decoys. Then we shoved our pirogues into a nearby stand of roseau cane. The cane and shallow muck stabilized the boats enough for us to stand in them with little danger of flipping over.

The bluewings came with the dawnsingles, doubles, and an occasional large flight. Our shooting was steady, and after an hour passed, Devlin and Mike each had their limit of four teal. I needed two more.

I hadn't noticed that the tide was coming in and that my boat was now floating. When the next teal buzzed in, I swung my shotgun hard left . . . and my pirogue flipped to the right. My fall lasted a millisecond. Then I made a four-point landing in thick black goop.

I was covered head to boots. I had mud in my hair and mouth. I wiped it from my eyes and roped it off my clothes. My hosts offered quick assistance before their grins broke into open laughter. After attempting to recover my dignity, I borrowed Devlin's gun and shot my last two teal.

Back at the launch ramp I tried to remain oblivious to bystanders' sideways looks and snickers, but I heard their comments: "Uh oh, looks like Devlin took anudder greenhorn huntin' in a pirogue, and he done gone swimming. Oooeee, I'd lak to have seen dat. He looks like a big oyster!"

You could read the anxiety in their bleary eyes. A hundred or more hunters huddled in small groups in the bare-lightbulb-lit room of the management area headquarters. They were whispering strategy and studying maps. Soon it would be time to assign spots to hunters who had reservations and allot leftovers to those waiting in the "poor line."

We were at the Grand Pass Conservation Area in west-central Missouri. Word was out: mallards were here in big numbers, so more hunters than usual had shown up long before daylight to take their chances in the drawing. Some would get to hunt. Others would have to go back home. That's just the way it was.

Missouri is one of several states that manage public hunting via a draw system. In this tradeoff between quality and quantity, a fixed number of hunters get a better shot at experiencing a primo hunt. My hunting partners and I hoped to draw a low number and get a spot. If we didn't, we'd come back the next morning and try again.

We got a spot that first day, but it was one of the last assigned. By the time we poled our layout boats into the flooded cornfield, the best places were taken. We set up in a less-than-prime slough, where we bagged only a couple of greenheads.

Back in line the next morning our luck improved. We drew a much lower number and claimed a better spota pool that had produced quick limits for all its hunters the day before. We poled out again, scattered our decoys across a shallow flat, and dragged our layout boats back into the standing corn. Then we crawled inside our boats to await shooting time and the morning feeding flight.

This time everything clicked. Dawn arrived cold and bright with a chilly west wind. The ducks worked our spread with little suspicion. We took turns shooting drake mallards, their green heads shining in the sunlight.

Like this one, many public hunting areas are operated according to special rules and restrictions: extra permits, drawings for spots, limited hours and days, and hunting from fixed locations only. Patience and perseverance are two keys to success on these areas. Often you have to endure some slow hunts to experience the good ones.

My recollections of public hunting also include pursuing puddle ducks and divers on DU projects across Canada, tolling black ducks in the salt marshes along the New Jersey coast, calling mallards through the flooded timber on Arkansas's famed Bayou Meto, and running and gunning on rivers and reservoirs throughout America's heartland. These and many other hunts have provided grand memories to warm the winter of my years, and given me the firm conviction that we must conserve the tradition of public hunting to ensure the future of our sport.

Many unsung heroes had the vision and foresightand indeed worked hard and sacrificedto ensure that we all have places to hunt waterfowl. It's our responsibility to pass on this legacy to future generations. Our heritage as waterfowlers demands no less.

Editor-at-Large Wade Bourne has been a full-time outdoor writer since 1979 and is the author of six books, including the Ducks Unlimited Guide to Decoys and Proven Methods for Using Them. Bourne and his wife, Becky, live on their family farm in middle Tennessee. Jack Unruh is an award-winning illustrator based in Dallas, Texas. To see more of his work, visit jackunruh.com.