Understanding Waterfowl: Science and Duck Calling

What kind of duck call sounds the most like a real hen mallard? Scientists conducted a study to find the answer

What kind of duck call sounds the most like a real hen mallard? Scientists conducted a study to find the answer

By Rick Kaminski, PhD; James Callicutt; John Patrick Lestrade, PhD; Rubin Shmulsky, PhD; and Mike Schummer, PhD

Researchers used a cassette recorder with a directional microphone to record the decrescendo calls of wild hen mallards in the field.

Female mallards produce a wide range of vocalizations, including decrescendo calls, feeding and flight assembly chuckles, and single and multiple quacks. While duck hunters use many of these vocalizations in their calling repertoires, the decrescendo may be the most widely imitated by waterfowlers. Typically consisting of five or six notes, the decrescendo begins with one or two loud, forceful quacks followed by a series of progressively shorter, softer quacks, as hens deflate their lungs. Famous waterfowl biologist H. Albert Hochbaum termed the decrescendo the “hail call,” because hen mallards appear to use it to greet ducks flying overhead.

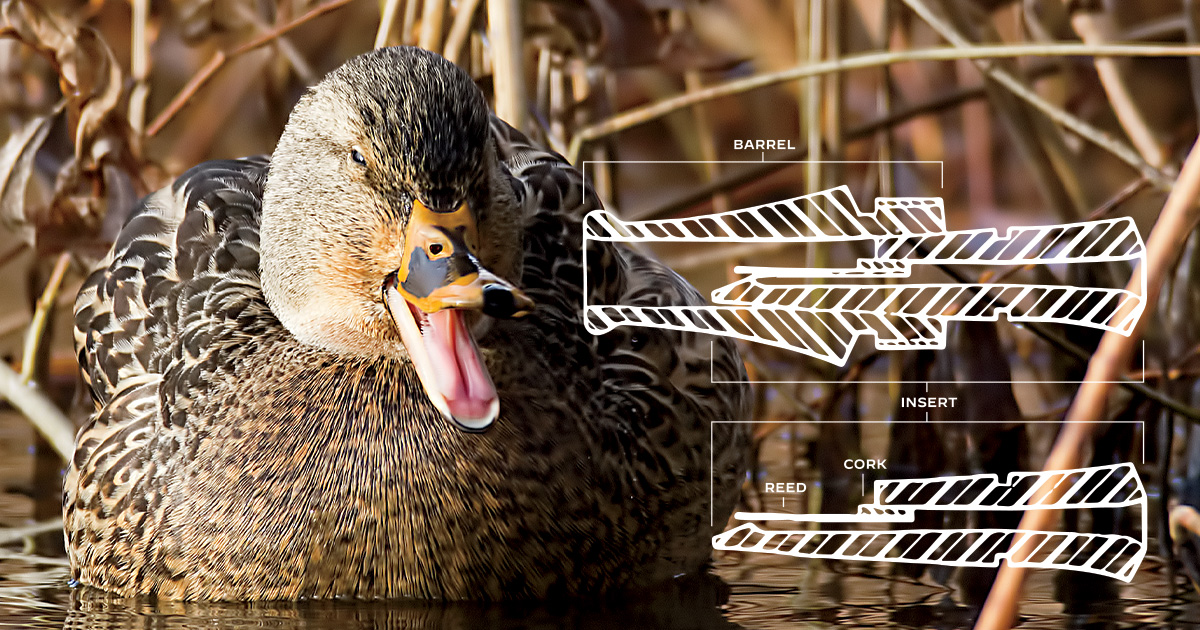

Duck calls originated in the 1800s and initially were simple handmade wooden, cane, or metal instruments with reeds that vibrated and produced ducklike sounds when the calls were blown. Today, duck call manufacturing has become a multimillion-dollar industry. Calls are available in a variety of models, styles, and materials, but most have either a single or double reed and many are made of wood or acrylic (a very hard, dense plastic).

To help duck hunters make the most informed decision possible when selecting a duck call, researchers at Mississippi State University (MSU) decided to compare the acoustic features of decrescendos produced by wild female mallards with those produced by duck callers blowing wood and acrylic calls. Here is what the study revealed.

The research was conducted through MSU as the topic of a master of science project by co-author James Callicutt. During the winters of 2008 and 2009, Callicutt and fellow students first recorded decrescendo calls made by wild female mallards to serve as reference vocalizations for comparison to human-operated duck calls. Recordings were collected in marshes, forested wetlands, and flooded croplands on public lands and private hunting clubs in Tennessee and Mississippi to ensure representativeness of calls across different habitat types. The researchers recorded 628 decrescendos using a portable cassette recorder with a directional microphone, but only vocalizations that were free of other background sounds were selected to be analyzed. Ultimately, decrescendos made by 38 different female mallards were identified and included in the study.

To ensure consistency among the calls used in this study, researchers employed a machinist to make identical duck calls from acrylic and from seven different hardwoods: osage orange, yellow poplar, black walnut, pecan, red oak, bocote, and cocobolo. Both single- and double-reed Arkansas-style calls were made using each of these materials. The machinist measured and digitally mapped the exterior and interior dimensions of a prototype call. Then, he used these dimensions to produce three identical calls from each of the eight materials on an automated lathe. The tone boards for each call were shaped using an automated mill. Researchers measured a prototype reed, which was used to produce identical reeds from sheets of .01-inch-thick mylar. Finally, a cork wedge was hand cut for each call to secure single or double reeds to the tone board.

A machinist was hired to make identical duck calls from acrylic and from seven different hardwoods. The custom-made calls, which were blown by volunteers, were tested using acoustical software to determine how accurately they reproduced the decrescendos of live mallards.

Volunteer callers were solicited via newspaper advertisements, social media, and bulletin board postings at MSU and local waterfowl management areas. Thirty-eight duck callers who rated themselves as “average to good” in proficiency were selected to participate. This group equaled the number of female mallards recorded for study.

Each caller was escorted to an outdoor test site for a recording session. Callers were positioned approximately 50 yards from the microphone, because most mallard decrescendos were recorded at approximately that distance in the field. Next, each caller listened to a randomly selected recording of a decrescendo produced by one of the 38 recorded female mallards and then attempted to imitate the call using the different hardwood and acrylic calls (including both single- and double-reed versions) manufactured for this study.

When the recording sessions were complete, the researchers used acoustic software to extract individual decrescendos of female mallards and human callers. Next, they employed sound analysis software to measure several acoustic properties of each note produced by the human callers and female mallards included in the study. Discriminant Function Analysis, a multivariate statistical procedure, was used to classify similarities and differences in the acoustic properties of these sounds produced by humans and ducks.

The researchers measured differences between the sounds made by human callers and female mallards based on the acoustic properties of entropy (rasp), pitch (shrill or soft), pitch goodness (pure or flat), frequency modulation (variation in pitch), and average frequency of notes (notes per second in the decrescendo).

Based on acoustic analysis, the most natural-sounding duck call was the cocobolo wood double-reed, followed in descending order by the osage orange double-reed, osage orange single-reed, pecan double-reed, acrylic double-reed, bocote double-reed, red oak double-reed, cocobolo single-reed, red oak single-reed, and walnut double-reed.

This research provided the first rigorous scientific analysis and ranking of acoustical similarity between decrescendos of wild female mallards and calling mimicry by humans using hardwood and acrylic duck calls. Modern acoustics technology enabled the researchers to reveal the most natural-sounding duck calls among the 16 call and reed combinations that were tested relative to recorded decrescendo calls made by live female mallards.

As one would expect, calling ability may partially influence how accurately hunters can imitate these natural duck sounds. The researchers assumed that the 38 human callers who participated in this study were representative of the broader hunting population at that time. And, because the same 38 participants were tested with each of the 16 different calls, variations in skill levels were captured in the study.

What are the most relevant findings for the average duck hunter? The researchers discovered that calls made of harder, denser materials generally produced more realistic mallard sounds than others. Consequently, the authors recommend that hunters should select calls made of acrylic or the hardest woods (e.g., cocobolo, osage orange, pecan, hickory, oak, and bocote). Moreover, double-reed calls performed better acoustically than single-reed calls, suggesting that reed type does influence call performance. The researchers believe that the raspier notes emitted by double-reed calls influence entropy and other acoustic features, allowing them to more closely mimic the vocalizations of wild mallards.

This study provides fundamental scientific information for selecting duck calls that sound most similar to hen mallards, which may help hunters and other waterfowl enthusiasts attract more of these birds into viewing or gunning range. The authors recommend that future studies be conducted in different habitats and for other species of waterfowl. Meanwhile, this research offers insights and options regarding the types of calls that you should consider keeping on your lanyard.

Dr. Rick Kaminski is emeritus James C. Kennedy Waterfowl and Wetlands chair at Mississippi State University (MSU) and retired director of the Kennedy Center at Clemson University. James Callicutt is an instructor at the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Aquaculture at MSU. Dr. John Patrick Lestrade is professor emeritus at MSU’s Department of Astronomy and Physics. Dr. Rubin Shmulsky is Warren S. Thompson professor of wood science and technology at MSU. And Dr. Michael Schummer is Roosevelt waterfowl ecologist at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry.