The Birth of Wildlife Conservation

A look back at how sportsmen and other concerned citizens saved North America’s wildlife and their habitats

A look back at how sportsmen and other concerned citizens saved North America’s wildlife and their habitats

By Jim Spencer

When European colonists first arrived in North America during the early 1600s, they discovered an abundance of wild game. Elk were common throughout much of the continent, and caribou ranged from the Arctic as far south as Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Michigan, and Minnesota. White-tailed deer and black bears were everywhere. And waterfowl seemed to blot out the sun on their migration and wintering grounds.

The colonists were amazed. In Europe, game was scarce and all of it belonged to upper-class landowners. Commoners were rarely allowed to hunt. But in the New World, things were different. The settlers needed game for food and clothing, and the animals were there for the taking.

There was so much game that the pioneers must have thought there would never be an end to it. How could just a few settlers with black-powder guns ever pose a serious threat to such an abundance of wildlife? But the human population grew quickly, and new settlers started arriving from many other European countries. There were fewer than 500 European settlers in all of North America in 1610, but 20 years later the number had grown to more than 4,000. Within another 100 years, over 200,000 Europeans were living in what would become the United States. By 1750, the population was more than 1.5 million. By 1800, it was nearly 5.5 million.

Wildlife populations suffered. Unregulated hunting and fur trapping were partly responsible, but an even bigger reason was the loss of habitat that occurred as settlers cleared the forests and grasslands to raise livestock and plant crops. By the mid-1800s, big game was largely gone from the eastern United States, but waterfowl were still mostly untouched. This was partly because ducks and geese used marshy, swampy, or flood-prone areas that were of less interest to the early settlers, and partly because big-game animals yielded much more meat than waterfowl.

Market hunters took a heavy toll on North America’s waterfowl before game laws were passed during the early 20th century. The most important was the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, which outlawed market hunting and established harvest regulations for waterfowl and other migratory game birds.

By the mid–19th century, more people lived in cities than in rural areas. But these city dwellers still needed food and clothing, and wild game continued to be a readily available source of meat and hides. Waterfowl and other birds were also shot in large numbers for their feathers, which were used to decorate hats. The short-lived but extremely destructive era of market hunting had arrived.

Because they were hunting for money and not for sport, market hunters developed bigger, more efficient guns than were used by sportsmen. The huge and now-illegal 8-gauge shotgun was a popular market-hunting tool because, as big as it was, a gunner could still fire it from his shoulder. Some market hunters used “punt guns,” which were basically long-barreled cannons mounted on small boats that could be maneuvered into position before firing. These guns could fire large quantities of shot at flocks of ducks as they rested on the water. This was sometimes done at night, using lanterns to confuse and attract the rafted birds. A well-aimed punt gun could kill a hundred or more ducks with a single shot, but even those market hunters who used conventional shotguns commonly killed 150 to 200 ducks per day. They also hunted the birds whenever they were available, in fall, winter, and spring.

For half a century, the hollow boom of the market hunters’ guns echoed across Chesapeake Bay, the Mississippi River Valley, California’s Central Valley, the freshwater marshes of Lake Erie, and the brackish marshes of coastal Louisiana and Texas. Millions of canvasbacks, redheads, black ducks, bluebills, mallards, Canada geese, brant, tundra swans, and other waterfowl were taken each year by commercial hunters, with no bag limits and no closed season.

By the late 1800s, the railroad era and the gold and silver booms had opened up the Far West and North to immigrants from all over the world. These new settlers quickly transformed the landscape from grasslands, wetlands, and forests to croplands and pastures intersected by a network of trails and roads. Waterfowl habitat was now in trouble.

The combination of market gunning and widespread habitat destruction on waterfowl breeding, migration, and wintering areas took its toll. All across the United States and Canada, duck and goose numbers fell rapidly. Still, few people gave any thought to conservation. Vast forests were cleared, partly to provide lumber for houses and industry, and partly to open the land for farming. In many cases, the trees were piled and burned just to get them out of the way. On the prairies, grasslands were converted to crops, and throughout the continent large tracts of wetlands were ditched and drained.

Although the colonists of the 1600s believed wild game was too abundant to be wiped out, by 1900 their descendants knew better. The once-abundant elk, bison, and deer were gone from large parts of their range, and many shorebird species were in real trouble. The passenger pigeon, once the most numerous warm-blooded animal on earth, was on the verge of its eventual extinction, as were the Carolina parakeet, Labrador duck, and ivory-billed woodpecker.

Many people were beginning to think that ducks and geese would become extinct as well, or at least so rare that hunting them would be pointless. No one knew anything about wildlife management. Very few people thought wildlife could even be managed.

Fortunately, some people didn’t think that way.

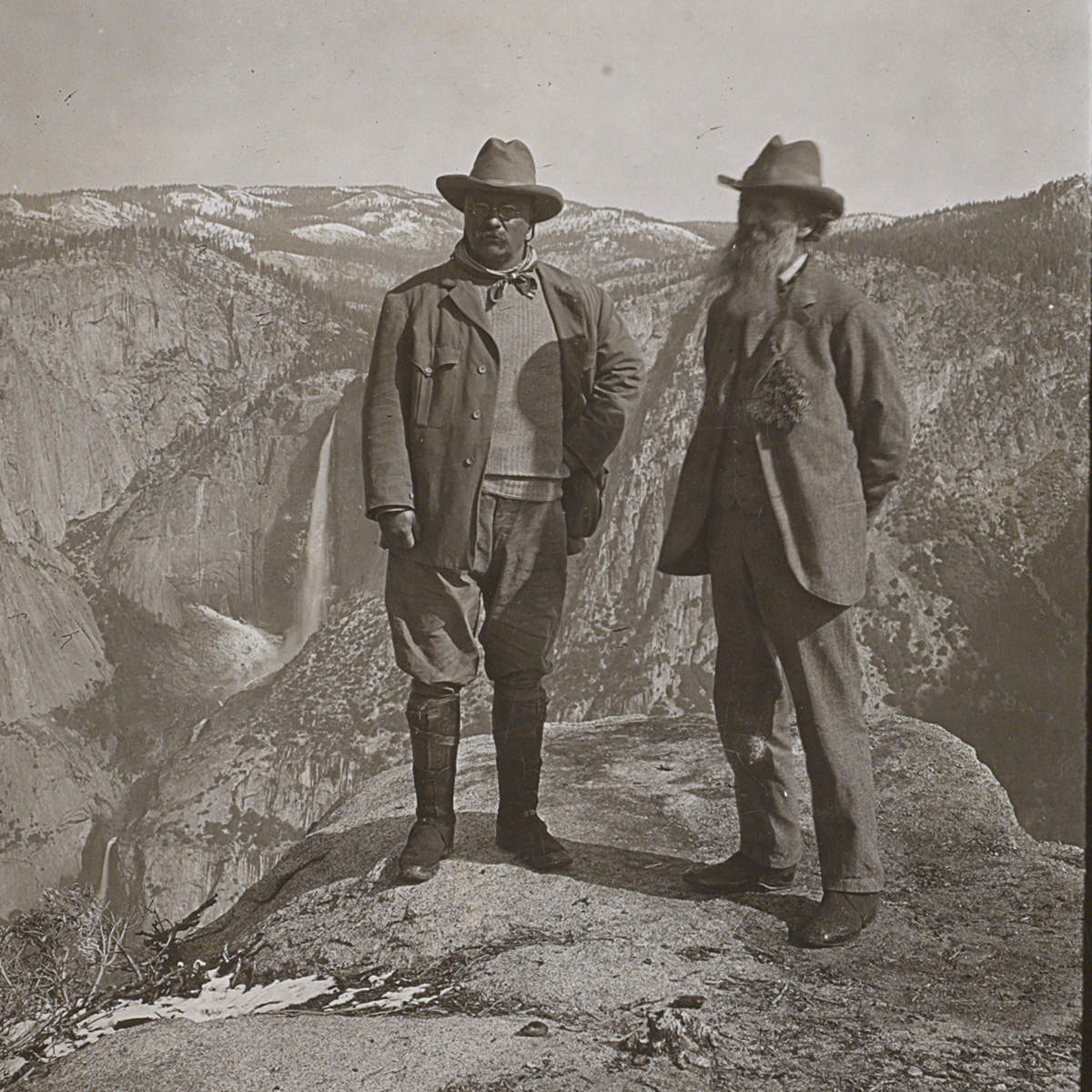

President Theodore Roosevelt (left) and John Muir were giants of the early conservation movement in North America. President Roosevelt created the first national parks and bird reservations and founded the U.S. Forest Service.

The first official attempt at natural resources conservation in North America occurred in 1871, when the U.S. Congress created the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries. Other conservation actions followed in the next two decades, and the conservation movement was launched in earnest when President Theodore Roosevelt took office in 1901.

Roosevelt was an avid hunter and nature lover. He knew wildlife populations were in serious trouble and was determined to do something about it. Roosevelt knew that protecting as much wildlife habitat as possible was important and did everything he could to accomplish it. Roosevelt established the first federal bird reservation in 1903, at Pelican Island in Florida. Before leaving office in 1909, he created 50 more. In 1942, these bird reservations were incorporated in the newly created National Wildlife Refuge System. Roosevelt also established numerous national parks, big-game refuges, and the U.S. Forest Service.

In the early 1900s, elected officials and concerned citizens had also started looking for ways to conserve waterfowl and other wildlife. In 1912, the Game Conservation Society was established. It was a forerunner of the More Game Birds in America Foundation, which eventually became Ducks Unlimited. The Audubon Society and the Wildlife Management Institute also had their beginnings in the early 1900s, and their efforts led to new laws protecting birds. A major breakthrough occurred in 1918, when Canada and the United States worked together to establish the Migratory Bird Treaty. Ducks, geese, shorebirds, and other migratory birds finally received the protection they needed. Mexico signed on as a treaty partner in 1936.

The Migratory Bird Treaty regulated waterfowl hunting seasons, outlawed commercial hunting, and banned the sale or trade of specified animal parts, including feathers and meat. Some poachers continued to hunt waterfowl commercially, but ducks and geese now had government protection. Most of the market hunting activity died quickly.

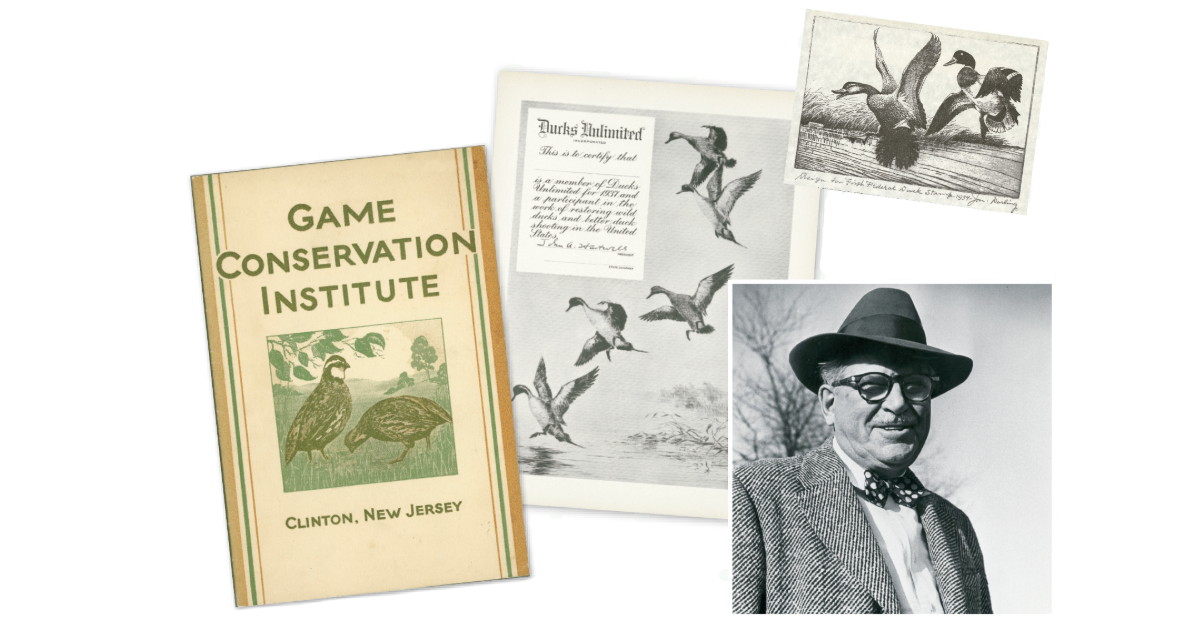

Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist Jay N. “Ding” Darling helped launch the Federal Duck Stamp Program, which has raised more than $1 billion for the conservation of wetlands and other wildlife habitats. The first duck stamp, which was designed by Darling himself, sold for one dollar.

Theodore Roosevelt wasn’t the only voice in the conservation movement. John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892. Gifford Pinchot, chief of Roosevelt’s newly formed U.S. Forest Service, believed in conservation as well as preservation. “Conservation” means using renewable natural resources but using them wisely so they can replenish themselves through growth and reproduction. “Preservation” means setting aside natural resources without using them at all. Today we preserve key tracts of threatened wildlife habitat and those species that are rare or endangered, and we conserve other natural resources and species.

Pinchot’s philosophy was to use natural resources “for the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run.” It’s that last part, “in the long run,” that is the biggest difference between the beliefs of the early settlers and the founders of the conservation movement. The early settlers gave little thought to the future. Roosevelt, Pinchot, and other early conservationists realized that if they didn’t plan for the future, wildlife and wild places would disappear forever. These forward-thinking people formed the nucleus of the conservation movement.

While harvest regulations helped many waterfowl species rebound, wetlands and other habitats continued to be lost at an alarming rate, and sportsmen realized that legislation providing funds for habitat conservation would be required to sustain waterfowl and other wildlife populations. In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Pulitzer Prize−winning cartoonist and avid waterfowler Jay N. “Ding” Darling as chief of the Bureau of Biological Survey, forerunner of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Through skilled and tireless lobbying efforts, Darling and his allies successfully pushed the Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp Act through Congress that same year—a remarkable achievement during the Great Depression. This act included the initiation of the Federal Duck Stamp Program. To date, the sale of duck stamps—primarily to waterfowlers—has raised more than $1 billion, which has conserved more than 6 million acres of wetlands and other wildlife habitats as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System.

The next major legislation supporting wildlife conservation in the United States was the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Act, or Pittman-Robertson Act, of 1937. Sponsored by Congressman A. Willis Robertson of Virginia and Senator Key Pittman of Nevada, the act established excise taxes on sporting arms, ammunition, and archery equipment. The shooting sports industry strongly supported this legislation, even at the risk of losing sales, at a time when most Americans had little money to spend on recreation. The USFWS distributes the tax revenues to state conservation departments, which partially match federal funds, largely with money raised from the sale of hunting and fishing licenses.

Aldo Leopold, who is recognized today as the father of wildlife management, believed that a “land ethic” was needed to conserve and wisely manage wildlife and other natural resources.

Establishing national wildlife refuges, national forests, preserves, parks, and other lands was an important step in saving waterfowl and other wildlife in North America. Setting hunting seasons, bag limits, and harvest regulations on game species was also important. So was outlawing the trade in feathers, meat, and other wild animal products. But conservationists quickly learned that most wildlife populations needed even more help. And so the science of wildlife management was born.

There are many notable wildlife management pioneers, but the most influential of all was Aldo Leopold. A lifelong hunter and outdoorsman, Leopold worked for the U.S. Forest Service for 19 years. He became professor of game management at the University of Wisconsin and went on to become the first chairman of the university’s Department of Wildlife Management. This was the first wildlife management school to integrate the studies of forestry, agriculture, biology, zoology, ecology, education, and communications.

Leopold is widely recognized as the father of modern wildlife management. The principles and techniques he taught in the 1930s and 1940s are still in use today. He is best known as the author of A Sand County Almanac, probably the finest collection of nature essays ever written. Leopold promoted the idea that a public “land ethic” was needed as the cornerstone of wise land use and conservation.

Until Leopold’s time, most people thought the best way to increase wildlife populations was to control predators and limit hunting. Leopold and others realized that habitat was even more essential to building game populations. At first, wildlife management was full of guesswork, trial, and error. But slowly the knowledge base grew, and researchers began to build on each other’s discoveries. New techniques were developed to measure the effects of management practices such as habitat enhancement and bag limits. That knowledge forms the basis of wildlife management today and helps ensure that all citizens can enjoy healthy populations of wildlife.

Excerpted from the book, A Beginner’s Guide to Waterfowling and Conservation, by Jim Spencer.