A Big Win for Green Bay

With help from the legendary Packers franchise and grassroots DU supporters, this historic hunting and fishing hot spot has made a remarkable comeback

With help from the legendary Packers franchise and grassroots DU supporters, this historic hunting and fishing hot spot has made a remarkable comeback

The sky was gray, the water was gray, the distant islands across the bay were a sooty smudge along a low gray horizon. It looked like the entire world had been melted down in a giant cauldron and poured out to congeal and harden in a monochromatic landscape of leaden skies and low waves like hammered pewter.

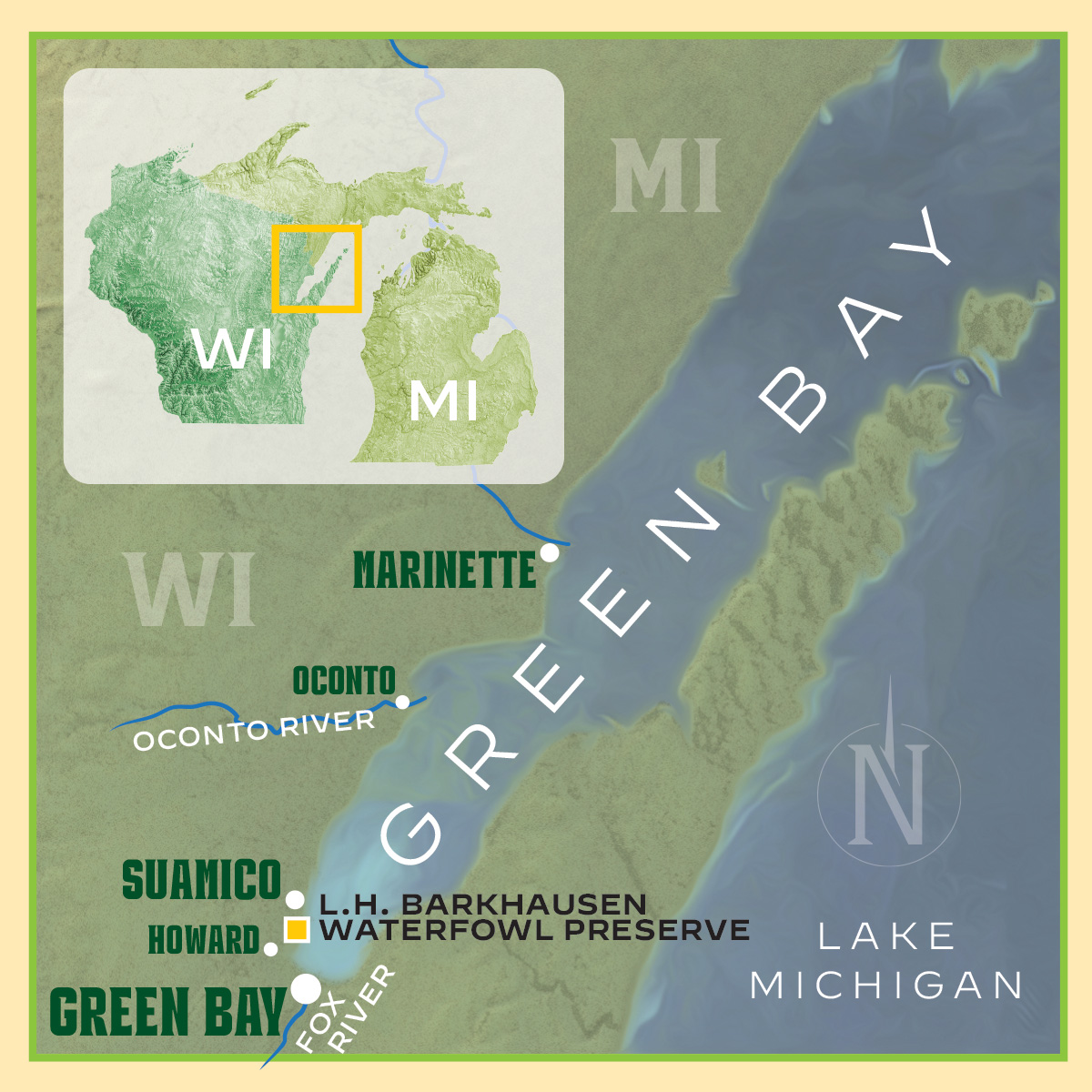

I was lying down in the middle of it all, in a layout boat anchored off the west shore of Green Bay, the famed 120-mile-long arm of Lake Michigan. Hemmed in by the soaring Niagara Escarpment to the east and the shoreline of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the west, Green Bay is a massive welcome mat to migrating ducks and geese. Here, bluebills and blue-winged teal and mallards and Canada geese arrive on the north winds, hell-bent on beating down the door in their flight from the rising tempers of Boreas.

Which means it can happen fast, or it can never happen at all. On this morning, moments after legal shooting light, we were fortunate to be in the crosshairs of the traffic. A group of 15 bluebills materialized off the right side of the layout, low to the water and heads bent with intent. In the next instant every bird was in range. In the moment that followed, every bird was out of range.

On the big waters of Green Bay, hunters deploy long lines of decoys in the hopes of intercepting flocks of bluebills and other waterfowl migrating through the area.

“Whoa, they’re fast,” murmured Greg Meissner, my cheery, gray-mustachioed gunning partner, who volunteers as a DU regional vice president. Water lapping against the metal hull of the layout felt like the back slaps of a doting father. It’s OK, boys. Maybe you’ll get ’em the next time.

The next time came 30 seconds later, with a pair of birds skirting the decoys. Meissner and I scooched deeper into the layout blind. “So cozy,” I grinned, just as the bluebills banked. They were on us in a flash, but they were on us close and committed.

We sat up in unison, shouldered shotguns, and fired at almost the same moment. Both ducks crumpled and hit the water, inside the decoys and bellies up.

“That was beautiful!” Meissner exclaimed. “They looked like they were going to land on the boat!”

Indeed they did. Such up-close-and-personal encounters are among the great attractions of a layout hunt, although some aspects of this specialized style of gunning are slightly less appealing. Neck aches, for example. Back cramps. Tweaked shoulder muscles from trying to reach the bag of breakfast snacks that’s gone MIA in the dark bottom of the layout.

But I wasn’t on the wild Green Bay just to enjoy myself, so I didn’t mind a few aches and pains in the cause of conservation. I was lying down on the job, in fact, in an attempt to answer a serious question: What on earth do the Green Bay Packers, spawning northern pike, the largest river cleanup in the world, and migrating scaup—a.k.a. “bluebills”—have to do with one another?

As it turns out, plenty, thanks to an incredible confluence of seemingly unrelated factors that could only happen in a place as special as this famed body of water.

Let’s start with a drainage ditch paralleling the blacktop on the east side of Lakeview Drive, in Suamico, Wisconsin, about five miles north of the city of Green Bay. It doesn’t look like much. It doesn’t look much different, in fact, from any of a million miles of roadside drainage ditches across the country. But in the spring, when this ditch fills with winter rains and snowmelt, it is full of spawning northern pike. Big northern pike, some of them 40 inches long and better. That particular ditch provides the only access from the open waters of Green Bay to an eight-acre freshwater marsh where each female pike lays up to 30,000 sticky eggs that attach to submerged grasses and reeds. The marsh is part of the 920-acre L.H. Barkhausen Waterfowl Preserve, created by and named for DU’s third president. Most pike return to their own natal marshes to spawn, or to marshes where they had previously spawned. Some pike might travel 20 miles or more to reach their historic spawning grounds. But development along the Green Bay shoreline has destroyed or degraded most pike spawning habitat in the region. This marsh was no exception.Long ago it had been turned into an agricultural field, grown in corn, soybeans, and alfalfa.

In 2013, during his first week of work as DU’s regional biologist in Wisconsin, Brian Glenzinski was called into the corporate headquarters of the Green Bay Packers for a meeting with senior staff and Mark Murphy, a Green Bay Packers Hall of Famer and the team’s president and CEO. Now manager of conservation programs for DU’s Great Lakes Initiative, Glenzinski couldn’t imagine what the football team wanted with a waterfowl biologist. “I walked into the conference room and Murphy and the others wanted to talk about what the Packers could do for conservation,” Glenzinski recalls. “I was stunned. I thought: How did I get here? What the hell kind of job is this?”

It was a job that was about to get quite interesting—and impactful. The Packers are the only NFL club that is a publicly owned corporation, and the only major professional sports franchise in the United States that is a nonprofit entity. The Green Bay Packers Foundation runs the team’s charitable contributions program, and has given out more than $19 million in community grants since it was formed. But it’s also a club whose fan base is crazy about the outdoors. “In Green Bay, other than those few home-game Sundays a year, life is all about hunting and fishing,” says Steve Kass, DU’s managing director of development for Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. In old photographs of Lambeau Field, he says, the stands are awash in blaze orange and camouflage. In the 1970s and 1980s, nobody had fashionable outdoor clothes. “When you went to a Packers game,” laughs Kass, “you broke out your deer hunting stuff.”

The old pike spawning marsh at the Barkhausen Preserve embodies the region’s deep roots in conservation, and the Packers’ commitment to community. With a $75,000 matching gift to DU from the Green Bay Packers Foundation, and with support from Brown County and the US Fish and Wildlife Service, DU led efforts to restore the marsh off Lakeview Drive. Stop logs were constructed in ditches and canals to aid in managing water levels for the benefit of both fish and fowl. Solar panels were installed to provide power throughout the preserve. Today, pike flood into the marsh in early spring, while mallards, pintails, wood ducks, blue-winged teal, Canada geese, and wading birds flock to the shallow, food-rich waters in the fall. The work helped kick off a flush of coastal restoration projects from Green Bay to Marinette, 55 miles north. The Barkhausen Preserve, as it turned out, was crucial ground not only for northern pike, but for the region’s signature collaborative conservation efforts.

Scattering wild rice seed in a restoration area along the west shore of the bay. Projects that bring back wild rice beds provide important habitat for fish and waterfowl and filter pollutants in water.

Green Bay had been in the spotlight for a while, explains Tom Olejniczak. “At the time the Barkhausen project was ongoing,” he explains, “the Fox River was undergoing the biggest EPA cleanup in the country.” The Fox flows into the bay right through metropolitan Green Bay. The Superfund project kicked off in 2004 and treated more than 6 million cubic yards of PCB-contaminated sediments from the bottom of the river. The state of Wisconsin completed its certification of the $1.3 billion cleanup just last year.

Olejniczak is one of the region’s most steadfast conservationists. The Green Bay attorney served on the Packers’ board of directors for more than 30 years and remains an emeritus board member. His father, Dominic, was mayor of Green Bay for a decade, served on the board of directors for nearly 40 years, and led the search committee that hired the legendary Packers coach Vince Lombardi in 1959. Today Olejniczak lives, and hunts, on the Fox River and remembers the heavy equipment pumping sand in the river in front of his home, encapsulating the toxic soils.

The Fox River cleanup, along with the Barkhausen project and other wetland restoration initiatives, is part of a slate of historic gains in wetlands conservation and ecological restoration. “The public utilities, towns and villages such as Howard and Oconto, the Packers Foundation—the way this area has rallied around conservation is inspiring,” Olejniczak says. “All the things going on along the west shore of the bay have made it an unbelievable haven for ducks.”

Seeing the transformation firsthand, I was champing at the bit to get a second swing at Green Bay ducks. But I’d have to bide my time.

An hour before shooting light the next morning found me at a Green Bay boat ramp, marveling—and cursing—at a massive line of thunderstorms raging my way. Giant bolts of lightning lit up a bay frothed in whitecaps. Our guide had already canceled the morning hunt. We were duck hunters without a duck hunt, for several hours at least.

With me was Kass, photographer Tom Martineau, Glenzinski, and a local duck hunter named Bob Spoerl. A beer distributor from Stevens Point, Wisconsin, Spoerl has risen through the ranks of DU from local banquet volunteer to his current position as the organization’s first vice president. He’s not the sort to give up easily. But when lightning sends you running for the truck, there’s no getting around the fact that suddenly you have time on your hands.

Which is when Glenzinski had an idea. “After this line of storms passes,” he asked, “who wants to plant some wild rice?”

Spoerl perked up. “Who wouldn’t?”

If the wide range of participants in the region’s nine-year-old wild rice restoration project is any indication, few would turn down the chance. Headed up by the University of Wisconsin−Green Bay, with technical support from DU and other partners, groups of students, hunters, anglers, birders, biologists, the Mole Lake Band of the Lake Superior Chippewa, and others help sow and grow wild rice along the west shore of Green Bay.

To tour the work firsthand—and take advantage of our free labor—Glenzinski loaded us and several hundred pounds of sopping wet wild rice seed onto his johnboat and motored out to the Duck Creek Delta, just offshore of the small village of Howard. Thankfully, planting wild rice is a straightforward task. Glenzinski plotted our progress on a GPS, where designated wild rice restoration areas were marked with bright red polygons. Once situated in place, Spoerl and I slung double handfuls of rice overboard. “That’s the scientific term,” Glenzinski laughed. “Just sling it out there, so it comes out in a spray, not a clump.”

Bringing wild rice back to the Green Bay marshes has benefits beyond migrating ducks and geese. Along with native bulrush and wild celery, which also have been planted in the area, wild rice helps filter pollutants and high loads of nutrients from the water and provides foraging habitat for northern pike. But it takes clean water to grow it. In the more urbanized southern portions of Green Bay, sediments in the water can blunt sunlight from reaching the rice seeds. In clean water the seeds can be three feet under the surface but the sun still finds them.

Spoerl was a newbie at planting wild rice, but I was a veteran. After all, I’d spent a full two hours the day before slinging seed into the coastal marshes at the mouth of the Oconto River. I told Spoerl about meeting the Oconto mayor, John Panetti, who helps put together wild rice restoration projects with the 94-year-old Oconto Sportsmen’s Club. Pulp and paper mills operated on the Oconto River as early as the 1890s and left behind an environmental mess. But pollution cleanup measures and restoration like the wild rice plantings have breathed new life into the Oconto marshes. From World War II until the mid-1980s, Panetti told me, the Oconto “was a dead river. There was nothing as far as fish and game. Now it’s turned around 180 degrees.”

Zach Stadler’s trusty Lab, Zoey.

Like the story of the pike spawning marsh at the Barkhausen Preserve, it’s an awesome community engagement story. “You see this all around the Great Lakes,” Spoerl said. “Saginaw Bay and Lake Erie are coming back. Look at what’s happening here in Green Bay. The grassroots are getting involved everywhere. People are waking up and saying, ‘We’ve got to do something.’”

For a Plan B to fill our time on a busted duck hunt, seeding native wild rice into Great Lakes shores where it hasn’t grown in half a century was a highlight, especially considering that some thought it couldn’t be done. Wild rice restoration is especially vital since the next 50 years could bring even greater change to Green Bay. As you think of climate change and what that might mean to waterfowl movements and changing migrations, Glenzinski explained, “it’s possible that ducks might one day overwinter in these areas. So, this work is going to support the waterfowl populations of the future.”

That might take a minute to wrap your head around, but there was a time when the remarkable comeback of Green Bay would have seemed no less improbable than the idea that Wisconsin might one day overwinter mallards and bluebills. For now, duck hunters are thankful that clean water is back, the wetlands are on the mend, and on those days when no one in their right mind would be out on the water, the ducks pour in.

On my last morning in Packerland, it was just me and Martineau on deck. Martineau hails from Minnesota, so he’s no shrinking violet when it comes to tough weather. As we pushed off the west shore, there was a lucky break in the heavy rain at dawn. But we knew things were going to get ugly.

As forecast, our weather luck didn’t hold long. By the time we motored to a long spit that jutted into the bay, rain dimpled the water and curtains of gray gloom hid the bay’s far shore. The wind was up and whitecaps broke over a nearby sandbar. It was down-and-dirty hunting. No blinds, no shortcuts. Martineau and I sat half in the water and half out, turning ourselves into blobs of mud among a scrub of low bushes and weather-beaten reeds. As guide Zach Stadler strung out ganglines of decoys—mallards clustered upwind and redheads, bluebills, and buffleheads downwind and slightly closer to shore—I declared to Martineau, “I’ll say this: It’s as ducky as it gets.”

Conservation efforts in the Green Bay area are helping to preserve the region’s rich waterfowl hunting traditions.

The birds felt the same way. Mallards stayed high and overhead, in singles and pairs, with bluebills zipping over the foam-stitched sandbar, in and out of the rain and fog like ash in smoke. But the blue-winged teal wanted to play, and with the lashing wind and rain, they held all the cards. Swarms of teal buzzed our little spit with near impunity as the rain on my hood nearly drowned out Stadler’s calling. For a duck hunter, it seemed like all was right in the world. After an hour-and-a-half into the hunt, I had but a single bird left to fill my limit.

But it wouldn’t come easy. The cruddy weather was worsening. The wind rose, sending whitecaps crashing into our shoreline. The boat ride back to the dock would be miserable. The rain pelted Stadler’s poor retriever, Zoey, rivulets streaming off her muzzle.

“That last bird always takes the longest, right?” Stadler said.

I kept my eyes open for birds and thought about his comment in the context of Green Bay’s long fight back to health. It’s hardly over. The Fox River is no longer curdled with PCBs, and marsh and wild rice restoration projects keep picking up speed. But Green Bay is no reborn Eden quite yet. High loads of agricultural runoff into the Fox still sicken the bay. Development pressures will only increase.

Stadler was right: Finishing a job sometimes seems tougher than starting it.

The rain fell harder and harder. We had to move up the mud bank to keep the rising waves from slopping into our shotgun barrels and camera lenses.

Finally, I’d had enough. “Alright,” I said. “Let’s bolt. Y’all have been a lot more patient with me than I deserve.”

Stadler grinned. “Good call, I think,” he said. “And just so you know, I don’t care all that much about you two boys, but I was starting to feel sorry for Zoey.”

I laughed. And who could blame him? With half the duck season left, and a Green Bay whose future looks better than its past, the last thing a duck hunter in these parts would want is a retriever nursing a grudge.