A Deadly Day for Duck Hunters

More than 150 people lost their lives in the Armistice Day Storm of 1940, including dozens of waterfowlers who were caught unprepared by the sudden, ferocious blizzard

More than 150 people lost their lives in the Armistice Day Storm of 1940, including dozens of waterfowlers who were caught unprepared by the sudden, ferocious blizzard

By Chris Madson

It was a hurricane. A hurricane 900 miles from the nearest ocean, on the ragged edge of winter with the thermometer hovering just above zero. The day the storm hit, and the night that followed, Dale Engler of Alma, Wisconsin, was out on Crooked Slough, a backwater on the Mississippi River about 50 miles southeast of Saint Paul, Minnesota. The memory still haunted him decades later. "I am very thankful that all I got out of that ordeal was frost-bitten feet and hands, frozen ears," he wrote in 1963. "I'm not counting all the nightmares I had the first few years after that day. In every single one, I'm still in that icy water, getting weaker and weaker, swimming toward a dark, snow-covered shore that is never there."

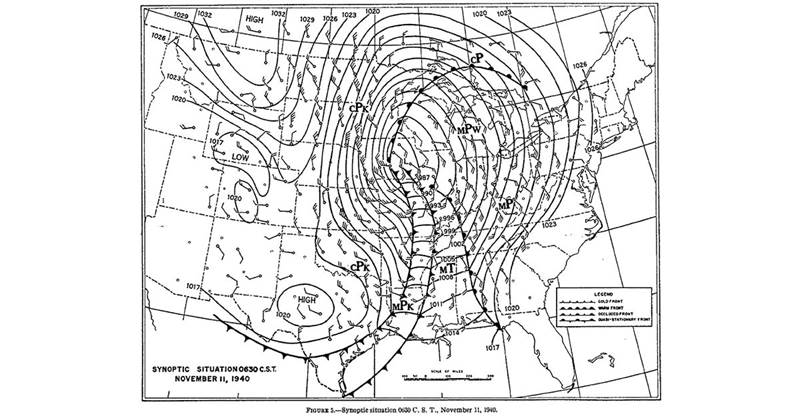

The storm was born in the gray expanse of the north Pacific, a low-pressure system that raised gale warnings along the West Coast during the night of November 6, 1940, and into the next morning. It roared up the Columbia River to buffet the Tacoma Narrows suspension bridge. The bridge's central span began to sway, and the wind accentuated the motion, like a kid pumping a playground swing. Just after 11 o'clock in the morning on November 7, the supporting cables gave way, and the wreckage of the bridge fell into the water 190 feet below.

The next afternoon, the system collided with the western edge of a mass of arctic air sagging down from Canada over the central plains. It was the first cold of the approaching winter. The storm skirted the edge of the front, drifting southeast into Colorado, strengthening slightly, and then swinging north along the eastern edge of the cold air. By then, a wall of frigid air stretched from Wichita, Kansas, to northern Iowa, and ahead of the cold front, a mass of warm air from the Gulf of Mexico surged up the Mississippi River Valley. Around seven o'clock on the morning of November 11, Armistice Day, as it was known at the time, the storm passed from Iowa into southern Minnesota.

It was the first cold front of the season after a long Indian summer, and it sparked interest among the area's duck hunters, especially those who were off from work or school because of the holiday. Frank Heidelbauer was a teenager living near Fort Dodge, Iowa. He would later become one of the nation's premier makers of custom duck and goose calls, but on that morning he was just another young waterfowl hunter looking for birds along Lizard Creek west of town.

"It was foggy with a light drizzle, and warm," he remembered 40 years later. "I had hunted about three miles of this stretch when a large flock of mallards hooked in out of the murk and landed almost in front of meI took about two steps and they were back in the air and I folded one for each of my three shots. It was while I was picking up these ducks that the wind suddenly thundered down on me out of the northwest.

"In all my days I can't recall such a rapid change in weather. With the wind came an almost unbelievable drop in temperature, and the drizzle changed to heavy wet snow. Where there were no ducks before, the creek was now full of them, and they were obviously worn out."

That's how it was along the prairie creeks in central Iowa. But as the storm continued north it became much more dangerous.

The center of low pressure passed almost 200 miles west of Chicago, but the Windy City and Lake Michigan were not spared. The wind mounted steadily from sunrise through the rest of the day, pummeling the area with gusts over 60 miles an hour for much of the afternoon. Barometric pressure dropped to 28.23 inches—equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane. The temperature at noon was a balmy 63 degrees. By six o'clock that evening, it had dropped to 26. The gale pushed the water of Lake Michigan to the northeast, causing a drop of 4.8 feet along the lakefront. The Milwaukee airport reported a wind gust of 80 miles per hour. In Minneapolis, the wind rose, and then it started to snow, the first flakes of what would be an accumulation of 16.2 inches in a 24-hour span.

As the storm spun toward the upper Mississippi, scores of duck hunters along the river laid plans to take advantage of the cold front. The weather forecast in the Minneapolis Star Journal on November 10 was terse but promising for a waterfowler: "Snow and Colder Today and Monday."

At 10 o'clock on the morning of November 11, the thermometer in Winona, Minnesota, stood at 50 degrees. A local weather observer recorded a shift in the wind and watched the temperature drop eight degrees in 15 minutes.

Around noon, Engler rowed his skiff across the backwaters to an island along the river channel. Like most of the young men along the river at that time, he knew small boats and hunting on the river. It had been raining lightly, so he was wearing a canvas hunting jacket, hip boots over canvas pants, and a wool shirt.

"At 2 o'clock the rain turned into wind-driven sleet and snow and within the next 2 hours I saw more waterfowl than I've seen in my life," he remembered. "About that time some hunters started to go ashore but I thought it was just an early snowstorm and paid no attention, besides, I was having the time of my life.

"Redheads and mallards by the thousands were flying over and on both sides of me. By this time those ducks coming down the river had gusts of a 60 mph tail wind behind them. Hundreds of ducks came past me within 15 feet, probably going around 80 miles an hour. At 3:45 I had 5 mallards and 2 canvasbacks, big plump northern ducks. Now [it was time] to get home and thaw out. Two hunters had been shooting off the south end of the same island I was on. I decided to walk down there and see if they had a big boat. Maybe I could bum a ride across Crooked Slough. Snow was falling so heavily by now that visibility was around 40 feet and it was getting dark. I got to the south area just in time to help both hunters out of the water. Their boat had broached and swamped . . . I saw I didn't have a chance with my skiff."

The three men tried to start a fire without success, and Engler decided he would attempt to swim across the backwater and get help. He stashed his shotgun, hip boots, and jacket under his overturned skiff and walked down to the water's edge.

"I couldn't see over 30 feet from me as I stepped into the raging water," he recalled. "The waves were about 3 feet high. Almost every wave was going over my head. I don't know how long I had been swimming when I bumped into a stump and found I could touch bottom."

On shore, Engler came across two hunters who had started a large fire. After he had warmed up, he made his way back to his car and drove home, where he called the authorities and reported the position of the two men on the island.

"It was the most miserable day I've ever lived through," he wrote, "and I have lived through a few other not-too-comfortable days while serving 38 months in the Pacific with the Navy during World War II. I've never been so miserably cold nor felt so close to death as I did in that freezing nightmare."

Three other young Winona men found themselves in similar circumstances nearby. Ray Sherin, only 14 years old, had gone out to the river around noon with his 20-year-old cousin, Bob Stephan, and 19-year-old Cal Wieczorek. They killed four ducks almost as soon as they hunkered down in the willows, but it quickly became evident that this was no ordinary cold front. Visibility dropped to 30 yards and the temperature was in free fall. They made a run for safety, but with no landmarks visible, they ran aground four times. Then the outboard died. The two older hunters dragged the boat off the mud bar and paddled in the general direction of shore.

The waves drove them onto a low islet. The two men jumped out, but before Sherin could move, a wave broke over the stern and soaked him to the skin. It was clear that they weren't going to find their way out of the bottoms until the storm abated. Stephan and Wieczorek dragged the boat up out of reach of the waves, turned it over for shelter, and made a bed for the teen, whose clothes were already freezing solid. With no way to build a fire, the three huddled under the boat and waited for morning.

"The thing I remember best was the unending scream of the wind," Sherin later said of the experience. "The sound of distant gunshots reached us several times. Far-off yells for help."

At dawn they launched the boat over the 50-foot shelf of ice that had formed during the night. Heading downwind toward Wisconsin, they ran aground on an ice shelf 100 yards from shore. A skiff from the Corps of Engineers' launch Chippewa picked them up.

Stephan was hospitalized for a week with frozen hands. Sherin, in far worse shape, spent six weeks in the hospital, fighting the lingering effects of hypothermia and extensive frostbite. He lost 58 pounds and part of one foot before he was released, just in time for Christmas.

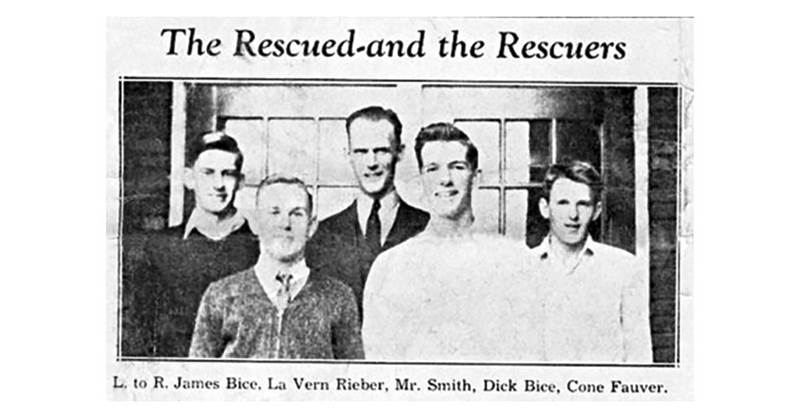

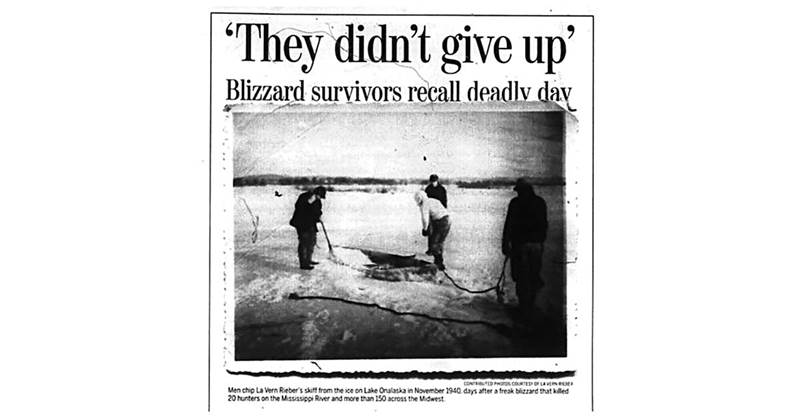

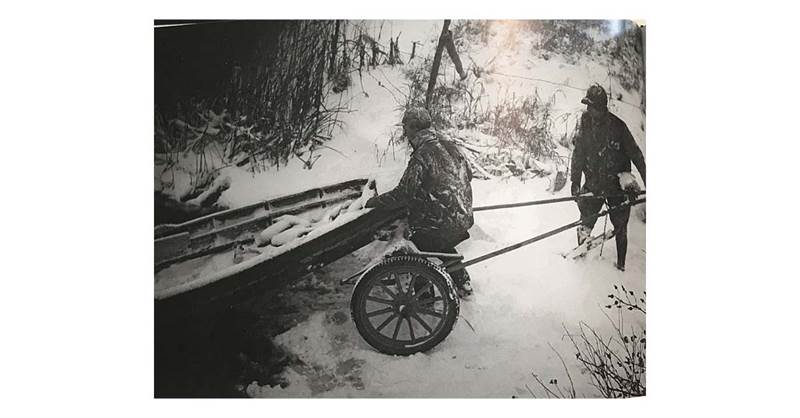

Two other teenage boys, Dick Bice and La Vern Rieber, paddled out to a collection of low islands and took cover, waiting for a flight. It wasn't long in coming. As the first bunch of mallards passed, Rieber killed a drake. He paddled out to retrieve the bird and, when he found that he couldn't get back to his friend, took shelter on another island. The boys could find no fuel for fires on their separate retreats, and precious little shelter.

When Bice's father, Ray, came home that evening and heard that his son hadn't returned, he loaded his 16-foot boat and motor, recruited some help, and hurried out to find the boys. The men tried to launch the boat, but the massive breakers swamped it every time they tried. They finally settled down to wait for a break in the wind.

The next morning, another river man managed to slide a boat over the ice to Rieber's island just as Ray Bice and his party arrived on the scene. The anxious dad slid his skiff over to his son's island, where Dick had trampled a ring in the snow as he ran in circles to keep warm. He was plenty cold but unharmed.

Others weren't so lucky.

Responding to news of the impending cold front, Carl Tarras of Winona gathered up his two sons, 17-year-old Gerald and 16-year-old Ray, along with a friend, Bill Wernecke, for a day of waterfowling on the river. When the wind shifted and intensified, they were cut off from dry land and took what shelter they could find in a stand of cattails. Gerald watched the other members of the party die from hypothermia—Wernecke first, then Ray. Carl held on until moments before rescuers arrived the next morning. Gerald had dug part-way into a muskrat house, the rescuers reported, a last-ditch effort that may well have saved his life.

Many details from other stories are lost forever. On the Wednesday after the storm, the bodies of Saint Paul hunters Roy Johnson and Thomas Cigler were discovered, partly covered with snow, on the shore of the mainland. Their johnboat had apparently been swamped by the waves. They made it to dry land but, soaked to the skin and with the wind-driven snow obliterating any landmarks, they had not found warmth and shelter in time. That same day, a Coast Guard searcher came across the body of Red Wing, Minnesota, resident Joseph Elk on an island in the river. On Thursday, the body of another missing man, Bror Kronberg of Saint Paul, was discovered. Kronberg had managed to get his boat to shore in the teeth of the storm, but searchers found his body under the lee of a haystack nearby, where he'd managed to burrow into the hay before he succumbed to the deepening cold.

Estimates of the total number of deaths vary. The National Weather Service reported that 154 lives were lost. Among those, 69 were crew members on ships and fishing boats lost on Lake Michigan. A headline in the Winona Daily News on the Thursday after the storm read "Death Toll of Hunters to Reach 20." On Wednesday evening, the LaCrosse Tribune's headline claimed, "27 Midwest Hunters Dead." With the news of the desperate conflict in Europe clamoring for attention, a close count of the number of hunters who were actually lost during the storm was never made, but it's likely that, of the 85 people not drowned in Lake Michigan, more than half were waterfowlers on the upper Mississippi.

Seventy years after the great storm, the children and grandchildren and great grandchildren of people who witnessed it still speak of it in hushed tones. It's as if they miss something that has largely disappeared from the heartland. The corn country of the upper Midwest has been domesticated. Cut over, fenced, furrowed, converted from prairie and forest to one of the world's great food factories, it has lost much of its essential nature. But the great weather events remainthe thunderstorms, tornadoes, hail, and blizzards that lie in wait just over the horizon, reminders that some things are still beyond our control.

It takes no great leap of imagination for a modern waterfowler to understand why hunters went out on the big water that day. They were an adventurous lot, that bunch. Like us, they whined about the bluebird days most of their neighbors welcomed, praying instead for a stiff north wind, a threatening sky, and a thermometer in free fall. While the rest of the town retreated to the fireside and drew the curtains tight, they went out to meet the storm and the waterfowl that rode it.

They witnessed a day when the business of men, and even the carnage of war, was overshadowed by the raw power of land and sky. It overcame some of them. For many more, it became the memory of a lifetime. All the wildfowl of a continent seemed to gather on a single arctic gale, the roar of the wind and the rush of wings an anthem to all that was—and still is—wild and free.

In 1971, the Michigan Historical Commission dedicated a marker in Ludington, Michigan, commemorating the tragic events of November 11, 1940.