Shoreline Sets for Diving Ducks

Explore shoreline sets for diving ducks and enhance your hunting success. Discover effective strategies and decoy placement techniques specifically designed for hunting diving ducks along shorelines.

Explore shoreline sets for diving ducks and enhance your hunting success. Discover effective strategies and decoy placement techniques specifically designed for hunting diving ducks along shorelines.

Greg Karnes is a partner in a hunting operation called Sportsman's Lodge in Sifton, Manitoba, west of gigantic Lakes Manitoba and Winnipegosis. From a waterfowler's perspective, this region has it all-big water and small potholes, and clouds of puddle ducks and divers. Karnes' guides lead his guests to a variety of shooting, but the lodge's specialty is gunning canvasbacks and redheads over decoys set along windswept shorelines bordering open water.

"I always hunt the downwind side of the lake," Karnes says. "I know most hunters believe you should hunt the upwind, calm side of the lake. But, ducks in sheltered water don't stir around much; they just stay put, whereas ducks fly better where the water's rougher. So, I go where the waves are rolling. They offer better shooting than flat-water areas."

Karnes, however, doesn't drop his decoys in the throat of a stout blow. Instead, he starts where the water is rough, then looks for some little break-a curved-in shoreline, the lee side of a point, or some other lakeshore feature that offers a pocket or sliver of water that's calmer than adjacent areas directly in the wind. "This is the key," Karnes says. "A flight of ducks will be flying along a shoreline, and they'll come to a spot that offers some protection from the wind, however slight, and there are several ducks-or decoys-sitting there, and boom! They'll pop in on them before you have time to get your safety off!"

One other important point: Karnes prefers setting up where the wind is blowing parallel to the shore. His whole decoy strategy is built around a crosswind. He moves around from one day to the next, picking his hunting sites to suit this criterion.

Karnes likes to shoot from the bank in a blind made out of reeds or brush, or he and his partners will simply sit motionless with their backs to rocks. "If there's some cover behind you, you have a face mask on, and you don't move when the ducks are coming, they won't see you, or they don't care. They'll barrel right in.

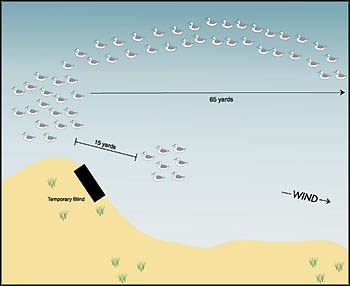

His diver spread consists of approximately four dozen magnum canvasback and bluebill decoys mixed together. First, he sets a dozen decoys in a clump some 15 yards out from the downwind side of the blind. Then he moves to the upwind side of the blind and drops another, larger clump of decoys. (The open space between these two groupings is approximately 15 yards.) From this second group, Karnes runs a double line of decoys that curves outward and downwind, extending like a half-moon some 65 yards distant.

"If ducks are flying parallel to the bank and into the wind, and they come to that extended line of decoys, they'll almost always follow it in and land in the hole between the two clumps," Karnes attests. "Now if the ducks are coming downwind (from the other direction), when they see the line of decoys, they'll hook around it and sail right into the hole. So, with this set, regardless of which way the ducks are coming, the shooting will be right in front of the blind."

Still, sometimes the birds don't land where he expects, and if this happens, Karnes is quick to adjust his spread. "The first couple of flights will tell you how the ducks are going to respond to the setup. If the first flight lands short, you can expect following flights to do the same thing, so don't wait to make your adjustment. Go on and do it right away. You might pull your decoys in closer to the blind or angle the curving line more-whatever you have to do to pull the ducks into good range."

Also, Karnes is quick to change hunting locations if he sees ducks working a nearby area better than the spot where he is set up. "That's one of the good things about not setting out too many decoys. You can pick 'em up and move quickly. And besides, you don't need all that many decoys for diving ducks. They're not the smartest birds in the world, and there's nothing complicated about pulling them in. If you just set out enough decoys to catch their attention when they're flying by, you'll have plenty of shooting."