Manitoba Marsh Magic

A waterfowler's pilgrimage to the Canadian Duck Factory and the birthplace of DU's conservation work

A waterfowler's pilgrimage to the Canadian Duck Factory and the birthplace of DU's conservation work

.jpg)

From the Ducks Unlimited magazine Archives

By Wade Bourne

The gusts were whipping the bulrushes back and forth over my head, their shadows like dancing tiger stripes across my parka. The blow was from the northwest and colda migration wind. Based on what Dr. Scott Stephens and I were seeing, or not seeing, many ducks in this area had hitched a ride on it and headed south.

Scott and I had waded into this wetland before dawn, tossed out a bagful of decoys, then hunkered down on marsh seats a few yards back in the reeds. His seven-year-old Lab, Brie, watched anxiously from her dog stand. Yesterday afternoon Bob Grant had seen streams of mallards using this marsh. This morning, though, only an occasional duck was flying by.

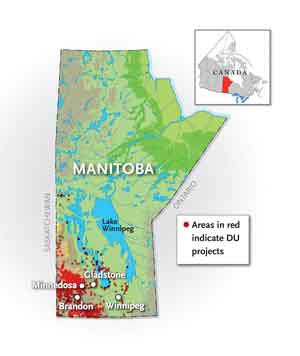

It was mid-October, and we were in the famed Minnedosa pothole region of southwest Manitoba. Bob is manager of operations here for Ducks Unlimited Canada. He calls this area the "best of the best" in prairie nesting habitat. And this year especially, water and adjacent upland cover had been plentiful. The ducks had responded by bringing off one of the strongest hatches in recent memory.

But even in the best spots, duck hunting can be dicey. The birds can change locations overnight. They can get temperamental about working to decoys, or changing weather can bring unexpected surprises, like the sudden departure of the ducks that had been using this marsh. Even in this storied country the stars have to align properly for hunters to experience those dreams hunts all waterfowlers seek.

But even in the best spots, duck hunting can be dicey. The birds can change locations overnight. They can get temperamental about working to decoys, or changing weather can bring unexpected surprises, like the sudden departure of the ducks that had been using this marsh. Even in this storied country the stars have to align properly for hunters to experience those dreams hunts all waterfowlers seek.

I was beginning to chill. The water was close to the top of my waders. It seemed like the wind was getting stronger and the sky emptier. My confidence was declining along with my comfort, and then I saw them50 or more mallards pitching into a patch of flooded willows a few hundred yards to the west. Maybe there was hope after all.

Several months earlier I had made plans to travel to this area to get a head start on the new season. I also wanted to check out freelance hunting opportunities on the many local Ducks Unlimited projects. DU Canada owns dozens of tracts in the Minnedosa area that are open to the public. What's more, hunting pressure on these projects is very light. Most shooting in southwest Manitoba is done on dry grainfields, where mixed bags of geese and ducks are taken from ground blinds. This leaves the potholes largely undisturbedan ideal situation for waterfowlers who enjoy gunning over water.

I phoned Scott, a longtime friend and DU Canada's director of operations on the prairies. Scott loves his work, and he also loves to pursue the fruits of his labor. He was quick to volunteer his services. "I'll pick you up at the Winnipeg airport, and then we'll head west," he said.

"Just bring your waders, shotgun, hunting clothes, and personal gear. I'll have everything else."

In Winnipeg, I met Scott at the curb outside the terminal. His truck was loaded with decoys and other essentials. Brie was nestled on a blanket on the back seat. We were two hours' drive from pothole country, and we were eager to get there, find some ducks, and set up for an afternoon shoot.

On the way, though, we had an important side trip to take. I wanted to visit Big Grass Marsh, DU's first-ever wetland restoration project in Canada.

Ducks Unlimited was founded in 1937 by a small group of hunter-conservationists who were concerned about trends in wetland loss and a resulting decline in waterfowl numbers. These men understood that many of North America's ducks and geese are hatched on Canadian wetlands, so they set about raising funds to preserve these crucial habitats for the future of waterfowl and the sporting traditions cherished by waterfowlers.

Big Grass Marsh near Gladstone, Manitoba (west of Lake Manitoba), was their first undertaking. Originally spanning 100,000 acres, this marsh was drained and cleared for agriculture in the early 1900s. However, instead of the fertile fields local farmers had envisioned, Big Grass Marsh soon deteriorated into a desolate tract of silt and dust. In 1938 DU Canada restored more than 12,000 acres of the marsh, which remains an important waterfowl production and staging area.

Bob Grant met Scott and me in Gladstone and took us on a driving tour of Big Grass Marsh. As we stood on the bridge over the channel that supplies water to the marsh, I had a sense of reverence for the efforts of DU's founders and the millions of sportsmen and -women who over the past 75 years have worked selflessly to conserve this continent's wetlands and wildlife. Big Grass Marsh was the first step in a very long journey.

From Gladstone, Scott and I followed Bob farther west to the town of Neepawa, on the eastern edge of the Minnedosa pothole country. Here we checked into a motel and quickly changed into hunting clothes. Bob also briefed me about the region's waterfowling opportunities.

"The best hunting in southwest Manitoba lies within a 50-mile radius of Shoal Lake," Bob said. "This area is dotted with thousands of potholes that were formed when the glaciers from the last Ice Age retreated from this area. They left behind enormous blocks of ice that melted slowly, leaving depressions that gradually filled with water from rain and snowmelt. Today these small wetlands constitute some of the very best waterfowl nesting and brood-rearing habitat in North America. Ducks Unlimited Canada owns some 100 conservation projects in this area and has easements on another 150."

Bob explained that in late summer, local ducks collect in large flocks and begin feeding in nearby fields of wheat, barley, and peas. "They will roost on potholes and fly out to the fields at dawn," Bob said. "Then they will return to water around midmorning. Hunters who locate these loafing areas can toss out a few decoys, hide in adjacent cover, and enjoy some great shooting when the ducks come back."

Effective scouting is the key to success. "There are many potholes, but they don't all hold birds," Bob said. "You've got to find the right ones. The best way to do this is to drive the back roads and watch the ducks' flight patterns. When you find a marsh they're using in the afternoon, you return there and set up to hunt the next day."

Bob had already located a spot for the following morning's shoot, but Scott and I were eager to get out this afternoon. We quickly piled our shotguns and gear into Scott's pickup and headed into the countryside. Scott and Bob had already enjoyed several good hunts during the season, which was now some six weeks in progress. And I had broken the icefigurativelya few weeks earlier, shooting teal in Louisiana. Still, our adrenaline was pumping as we started driving and looking for ducks. Those hunts were then. This one was today.

Fifty miles later we had a reality check. We'd glassed several marshes and found a few ducks on most of them, but no concentration on any. Bob looked perplexed. "We had a ton of ducks on these marshes just a couple of days ago," he said, "but it seems that a lot of them have moved out.

Sometimes we get a lull between when the local birds leave and the northern migrants arrive. Looks like that may be the case now."

Just my luck. We were in one of the best duck spots in North America with the man who knows it probably better than anybody, and we'd hit a lull. Talk about bad timing!

Still, Minnedosa at its slowest is better than most duck hunting areas at their peak. We decided to keep looking for the best possible spot. Then we'd set up and see what the winds blew our way.

Finally, after an hour and a half of driving, we topped a rise and bore down on a large marsh that held around a hundred mallards and an equal number of bluebills. "We're running out of daylight," Scott said. "I think we should give this spot a try."

Bob and I agreed, and soon we were wadered up and packing decoys from Scott's pickup. The wind was howling from the northwest, and the mallards were crowding the pond's western bank to get out of the blow. There was a border of thick bulrushesperfect for cover. The low sun would be at our backs. The setup looked ideal. As we walked in, we flushed several dozen mallards. Soon we were perched on marsh seats a few yards deep in the cover, watching our decoys scuttle in the chop.

In the next hour, action wasn't fast but it was steady. Ducks began trickling back into the marsh, and we traded shots, taking a mixed bag of 14 mallards, gadwalls, and bluebills. We also downed two Canada geese that came head-on to our calling.

I had a good feeling as we picked up the decoys in the fading light. We'd had a nice start to our hunt, and I was on the Canadian prairiethe heart of the Duck Factorywith two amiable, highly capable hunting partners. There was only one more thing I could ask for. "Bob, you know a good local restaurant?"

"I do, indeed," he answered, and we headed back to town for a hot meal.

The next morning Bob was confident that a large concentration of birds would still be using a 50-acre pond on a DU project he'd scouted west of the town of Minnedosa. We arrived on site before sunup, hiked to the upwind side, and tossed out our mallard decoys. Scott also stretched a long line of canvasback decoys toward the center of the pond. Bob had seen several cans and redheads here, and with luck the decoy line would funnel some in close to our hiding spot in the bulrushes.

But nature tossed us a curveball. As the sun rose, a thick fog developed. Soon we couldn't see 10 yards. The ducks were therewe could hear their wing beats as they flew by. Occasionally a duck pitched out of the murk, and we came up firing. By 11 a.m. we'd downed nine birds, a mix of puddlers and divers.

After lunch at a historic hotel in the farming town of Rapid City, we continued searching for birds. We drove scores of miles and checked several marshes, but we never found the concentration we were looking for. More and more it seemed that Bob's pronouncement of a lull was accurate. We finally decided to set up on a beaver pond where we had flushed a few dozen mallards. Bob continued scouting while Scott and I hunted. Our bag for the afternoon was seven.

Bob was optimistic when he picked us up at dark. "I found a wad of mallards resting on one of our marshes and feeding in a grainfield nearby," he informed us. "I think we'll have some action tomorrow." That was good news to sleep on.

The next morning the wind was blowing harder than ever, and the temperature was close to freezing. The sky was clear as we set our decoys. There was only one element missing. The mallards Bob had seen the previous afternoon weren't here. Only an occasional bird flew across the marsh. In the first hour of hunting we bagged one lonesome greenhead and a Canada goose that came to our calling.

Right after the goose fell was when we saw the mallards swoop into a nearby timber hole. Bob said there was another smaller pothole there that was more protected from the blow. As we talked about moving, another flight pitched in to join the first group. That's all the convincing we needed to pick up and head in their direction.

Thirty minutes later we were huddled beneath thick bushes bordering the small pond. Our decoys were set where ducks had flushed upon our arrival. Now maybe our luck would change.

A few minutes later a small flight of mallards dropped into our spread without circling, and we downed three.

And that was it. Only one other bunch appeared over the next two hours, and those birds settled across the trees in another nook of the pothole.

The slip. That's what the ducks had given us. Oh, we'd bagged several, and I'd gotten a firsthand look at this storied part of prairie Canadaso important to waterfowl and so tantalizingly available to hunters. But many of Manitoba's ducks had headed south just as I was coming north. I'd come to the right place but at the wrong time. That's just how duck hunting is sometimes.

I took solace in the knowledge that this afternoon I would be flying back home and leap-frogging ahead of the migration. I'd be waiting on the ducks' wintering grounds when they got there, and this time they would hopefully play by my rules. Soon it would be Minnedosa mallards in Missouri rice fields and Kentucky flooded timber, and this time I would have home field advantage.

As I boarded my plane in Winnipeg I was optimistic both for the days ahead and the seasons to come. The Minnedosa area, and especially the DU projects there, were in prime conditionlush with water and upland cover, and they had yielded an abundance of waterfowl this year. And thanks to the hard work and generosity of DU members everywhere, the habitat conserved on DU projects will be there in perpetuity. From Big Grass Marsh to Minnedosa and beyond, the vision of DU's founders has come to fruition. There's still much work to do, but there's also much that's been completed. I just wish those farsighted gentlemen could come back and see what they started.

The website also provides links to a wealth of other important information for waterfowlers, including the latest provincial hunting regulations, required licenses and permits, and professional outfitter associations (for those who wish to hunt with a guide). Moreover, this site provides timely updates about DUC's conservation programs and Canadian waterfowl habitat conditions as well as trivia, recipes, tips, and more.